Graham Reid | | 14 min read

Todd Rundgren: Hellhound on my Trail (from Johnson)

Todd Rundgren laughs as he predicts

the end the current model of on-line music sales which will disappear

like the Sony Walkman and vinyl singles: “Because some songs are

priceless, some songs are worthless . . . and some songs are worth

exactly 99 cents”.

He should know. In a 40-plus year

career he's made songs, and whole albums, in each category.

However although he has appeared on

over 40 albums under his own name or that of his bands (the Nazz in

the 60s, Utopia from the mid 70s), been producer for everyone from

the New York Dolls and Patti Smith to Meat Loaf (Bat

Out of Hell), Shaun Cassidy

and the Psychedelic Furs, Rundgren allows himself another dry laugh

as he describes his position in the marketplace of music.

“I'm a fringe artist.”

Given his long career – which

admittedly has only troubled the American top 20 singles charts with

I Saw the Light

and Hello It's Me

in the early 70s – you'd think this innovative musician who was

also in the vanguard of video and

internet technology would

be a household name.

But if he's known for anything

today it's as the man who acted as father for actress Liv Tyler –

daughter of Aerosmith's Steve Tyler – when she was a child.

An amusing and almost detached

observer of his own career, he notes a rare experience when he

fronted the New Cars in 06 – the old Cars with him in for lead

singer Ric Ocasek – and discovered a very different audience

response from what he was use to. He admits people come to his shows

expecting and wanting Hello

It's Me “and I mostly

don't play it because it's too out of context of what I'm doing at

the time”.

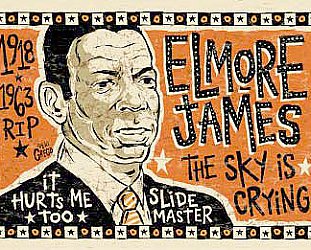

Rundgren's

wayward career has taken him from soul-pop through expansive

prog-rock, from guitar hero to abandoning the guitar entirely. Yet he

is currently out playing a programme of blues by the legendary Robert

Johnson (1911-38) delivered in the style of the late 60s power-rock

bands like Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. His new album is

Todd Rundgren's Johnson

– a title more risque to an American audience.

And he

picks up a local rhythm section players when he comes to Australia

and New Zealand later this year – and his visit is a surprise, even

to him.

Just like the traveling bluesmen of old, just being a troubadour?

(Laughs) There

has certainly been no up-tick in my record sales that would cause me to be

popular Down Under, but my association with Hal Wilner brought me to

Australia in January to do a Sydney summer festival and this was a

fairly significant event, so I got a lot of direct exposure and

coverage by the press. That was the necessary foot in the door to try

and pursue some sort of tour.

The

record only requires a quartet and a lot of people are familiar with

the material, so it is plausible to pick up a rhythm section: my

principal guitarist will rehearse the rhythm section before I get

there.

And why

versions of Robert Johnson at this time?

I went

through an era where I almost eschewed electric guitar, my focus went

elsewhere and I wanted to become a better singer and performer. So

for a number of years I would front a large band and never play the

guitar, never play any instrument, just dance around and sing.

I got

back into the guitar some years ago and in a big way. I wanted to do

an arena rock-style record – the record was Arena – but like so

many artists of my generation – and maybe everyone these days –

you get your material distributed independently. No one I know has

any major company, five-record deal.

So it

came time to do distribution for Arena and the company that made the

deal also happened to administer the Robert Johnson music publishing.

They made as a requirement to distributing Arena that I record an

album of Robert Johnson tunes as well. They claimed to me that they

were getting many requests for Johnson songs to be used in films and

tv shows, essentially the mechanical license.

While

they had the publishing they had no recorded versions so they

required I make a record. I agreed to do it mostly because I wanted

to get my record out and thought I would figure out how to deal with

this later.

To my

chagrin when I got around to doing it, it turns out Eric Clapton had

been making a second career out of tributing Robert Johnson. After U2

did a song I was crestfallen, what was I going to do?

One of

my heroes [Clapton] has already done it so anything I did would pale

by comparison if nothing else. And the whole process will be creepy

for me, constantly trying to outdo Eric Clapton.

It took

a year and I came to the conclusion I was not directly influenced by

Johnson, Eric Clapton was – and I was influenced by Clapton.

So I am

not attempting to compete in my authenticity.

Another

fortuitous coincidence was that my first gig as a professional was in

a blues band so I understand the idiom. It wasn't a ridiculous leap

to deconstruct and reconstruct this material into a way I was

comfortable with.

But it

is no way “a tribute”, you won't see those words anywhere there.

The

entirety of Johnson is 40 - 45 minutes and that's an opening act. My

shows are usually two to two and half hours, so of necessity I'm

going to have to fill it out. The blues guy I know best is myself. My

big initial influence was electric blues – and English people who

did their own version of that. So all throughout my career are

examples of my modernised or twisted take on the blues idiom.

My first

band the Nazz, whose career was done by 69, and on the second record

we rip off John Mayall and the Bluesbreakers featuring Eric Clapton.

In

concert we may play a few songs people are actually familiar with.

In many

ways the diversity of your career allows you to do pretty much what

you like these days.

I don't

believe I have much in the way of radio success, that is a great

advantage to me because people send me notes saying, 'This show will

be total shit unless you play this song'. This is helpful.

You've

been quite good about revisiting your earlier work and playing albums

in their entirety: you're soon doing The Healing and Todd albums.

I have a

devoted audience because through this process of not playing what

people expect me to play I have weeded out all the dilettantes. So

now the audience I have is particularly devoted and will come to see

anything I have to present. And if it is in package form will

purchase anything I have to present. But a lot of it depends on a

certain recognition that they need to get every once in a while and

deeply desire.

They

come about through Rundgrenradio.com . . . the guy who runs it plays the

music and does interviews with anyone even tangentially related to my

career, and it has a substantial hardcore following and go to for

information. They decided they wanted to dabble in promotion and

polled their audience and they [The Healing and Todd] were the

records they wanted to hear.

No one

was expecting the level of production that went into the first one,

it is more a theatrical representation of the record . . . so now

the expectation is high.

I'm

interest in the fact that you also do what we might call re-creations

of music – for example the Beatles on Deface the Music, the covers

on Faithful and your own music in With A Twist . . . why??

The

Nazz's first song was Open My Eyes – which was the Who and Beach

Boys mashed together – and on the B-side was Hello It's Me, it was

a dirgy version where I played vibes, and for some reason the record

got flipped and it became a minor hit.

Years

later when I wasn't a radio staple I was doing the Something/Anything

album and the album consisted of me playing most of the instruments.

It turned into a double album and by the last side there was enough

of me playing by myself and wanted to do live-in-the-studio

performances with no overdubs.

So I did

half a dozen songs and one was a reworking of Hello It's Me with a

more modern groove, background chorusses and a horn section. I did it

because I thought it was a different way to do it, I was in a

singer-songwriter phase.

In never

thought about radio play but the biggest single became Hello It's Me

and other bands covered it, like the Isley Brothers.

That's

the song that if I don't play we have people walking out – and I

mostly don't play it because it is too out of context of what it is

I'm doing. If there was a context then I'd play it.

So I

just thought I heard it in a more personal way and that's why I

redid.

The

moral of the story is I not only improved it in how the song could be

interpreted, but it turned out to be a gigantic financial boon.

The New

Cars must have been a different experience again?

Yeah,

the thing that hit me the first time we played in front of an

audience, we were eight songs in and people were still singing along.

Which is completely different from my shows. If there are people at

my shows who haven't fully kept up they are going to be stumped at

several points in the show trying to remember where, if ever, they

have heard this song. Plus I have this nasty habit lately of whatever

my newest record is, I play the whole thing. And then give them the

crumbs of older material.

That

[New Cars] was an experience I haven't had on stage, that power of

familiarity. You are not trying to sell anything, when they hear the

first note they are fully committed and the song is sold.

It's

part of your performers tool kit, you want to get the audience going

and you are going to over indulge yourself and play some old jam . .

. but you know at the end you have to play something they are

familiar with, and it doesn't matter if it is Louie Louie.

You have

had a long and diverse career in production. What attracts you to a

project?

It's the

material – which I think goes along with the priorities of most

listeners. The thing they care most about is a decent song. They

don't want to hear the most incredible version of the world's

crappiest song. They would rather hear a half-assed version of the

world's best song.

You are

always striving to hear what it is in the material that might be

attractive to a listener, and that's the most time-consuming aspect

for me of the process.

Early in

my production career I didn't vet the material too much, I figured

we'd get in the studio and the combined talents would work out the

problems. And for a lot of things that did work.

I had

overconfidence in my own songwriting and if people didn't produce the

goods I would just take over.

But if

you develop some recognisable style, if you apply that to production

you put your paw prints on everything you do, instead of letting the

act put on their display, warts and all if necessary.

If their

songwriting is weak and some label has decided to put the record out

anyway then they are just going to have to live with the weak

songwriting.

In the

Seventies a review in Rolling Stone could make or break you, but you

can't second-guess the taste of a critic let alone the buying

audience, you have to have another vision of what you are trying to

accomplish. I consider more timeless aspects of music . . . it's the

phenomenon that gets Sinatra's Capitol recordings of Fifties

rediscovered.

Some

records don't get recognition but grow in stature.

You have

to think like a musician – which can be hard if you are working

with people who got paid a whole lot of money before they did

anything which became the model. 'Here's the seven-figure advance,

now make a record'.

But what

did musicians do before we had a record industry, which is only about

100 years old? How did they live?

First,

they were probably better musicians than today – but you got you

paid for your performance so you had to hone that and be sharp --

today we are getting back to that – and the material had to stick

in people's head somehow.

If they

could just forget about you, you'd have no follow-up business.

The

problem happened when the music industry discovered that music could

be commoditised and success was no longer measured in the size of the

audience you paid for or even, go forbid, how the local critics

responded.

It

became about figuring out what the buying patterns were, and it was

all the Arbitron rating system, people in a room with a dial and an

aggregate score.

If a

number went below a certain point the record would never get

released.

But most

people are so unsophisticated they don't now what a chorus is (Laughs)

So

basically you still listen for a good song?

The

material doesn't have to be super-confident, it just has to be done

with brio or some perceptible emotion. It also doesn't have to be

technically perfect.

The

thing people care the least about – which is the thing some

artists, to my mystification are most obsessed with – is the actual

sound quality.

Most

people don't have studio-referenced sound quality. Since people

started listening with earbuds, how can anybody figure out how to

mix? There is no uniformity to how people listen.

Most

sound systems come with distortion, like superbass, which most

musicians try to keep out of their records. If there is any muddiness

in the bottom end of the mix you've made you will rattle the walls

and will sound horrible.

Is music

still important? It seems like just another entertainment thing in

the marketplace today.

As it

became portable it became just a lifestyle accessory. It always has

been in some aspects, there are always bands or acts meant for the

musically naïve, like Taylor Swift. As people get older their

experience grows, and seeing it performed live they realise that

human beings do this, it's not all machines.

Like

when you listen Sinatra's Capitol albums, they were mostly all one

take, no overdubs, a 50 piece orchestra and the singer all locked in

– and it is the performance they will strive to perform live from

there on.

The Sony

Walkman changed everything: random access, skipping over songs, that

ate away at the album being principle form.

This is

why the Internet model for selling music will eventually fail . . .

people will realise that some songs are priceless, some songs are

worthless and some songs are worth exactly 99 cents.

There is

another new model out of Disneyworld: the new Mickey Mouse club

singers who grow up with their audience. For some artists that is a

close link with their audience for an album, and a guaranteed sales

figure.

I used

to do two solo albums, Utopia and three production jobs every year.

Then variety and eclecticism was a selling point, now it seems there

are too many artists are trying to cram into the same space, all of

the Linkin Parks . . .

Some of

what you have done is very amusing – I'm thinking of Meat Loaf's

Bat Out of Hell – but humour and wit seems to be missing in music

these days.

Yeah, it

is pretty humourless, although it is there in some aspects of hip-hop

– Flavour Flav is a pretty funny guy. But I'd like make a record

like Absolutely Free, just a pastiche of guys musically goofing in

the studio.

Of

course Zappa asked 'Does humour belong in music?' Like Led Zeppelin

said, 'Does anybody remember laughter?'

They do,

the audience is prepared for it, comedians are filling sports arena

now. If you have a choice of going into comedy or music these days

I'd say your odds are 50:50.

Of

course, if you are in a band you have to develop a sense of humour as

a survival mechanism.

It's

pretty deadly if you wind up in a situation with someone who has no

sense of humour. It can make for some long and uncomfortable bus

rides.

You've got to have a sense of humour in this day and age, it's too easy to fail.

Peggy in America - Oct 8, 2019

Thank you, Graham, for such a wonderful interveiw! At least, for me, of his time, beginning, and continual influence. I AM obsessed with production values, and have often noted his name upon them. My first experience of him was The Nazz. I'd just met a fella that was a band promotor, producer and such, and he DID have a set of Altec-Lansing Voice of The Theatre speakers in the house, a-hem!, but when "If That's The Way You Feel" came in, I literally felt an out-of-body experience. I've never forgotten it, either. I literaly felt lifted up, off my chair, and as it built, I simply .. drifted out of myself, rising in the enveloping sound, carried along, and then, just as easily, brought back down. Not stoned, not tripping, but simply - experienced. Perhaps I was reminded that I was not entirely unfamiliar, having near-drowned at age 5, but always having remembered the experience under the water, and having been levitated, at age 11, at a seance. Same sort of experience - a separation of self and body. And like anything else, a first-listen can never come again, but the song can still place me there, to this day. But it is the precision of the recording that did that, as much as the building melody itself.

SaveHe's a very cool cat, always within the radar range of all the folks he mentioned, (include me!) and it was great to hear from him. Astute, and one smart cookie. Here's to lookin' back at'cha, pal!! Thanks for it all.

Peggy in America

post a comment