Graham Reid | | 3 min read

The Shangri-Las: Remember (Walking in the Sand)

Only a fiction writer could make up the life of New York's George Morton, the man who got his nickname "Shadow" because he would simply disappear from work for days at time and whose private life few knew anything of.

He was a diligent alcoholic (until hitting a Betty Ford Clinic in the Eighties) and doubtless that explained some of the disappearances. But it was when he was around that things were even more interesting.

A fiction writer could perhaps convince you that as a songwriter and record producer Shadow Morton was there for Iron Butterfly's Inna-Gadda-Da-Vida and the heavyweight sound of Vanilla Fudge as well as recording the teenage Janis Ian (her pivotal song about cross-racial love Society's Child which resulted in death threats) and hits for the seminal girl group the Shangri-Las.

He's the guy who produced Leader of the Pack and co-wrote it with Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry.

There's hardly a common thread there -- nor between the Beattle-ettes whose '64 Beatle pastiche Only Seventeen rode the wave of Beatlemania and the trash rock'n'roll of the New York Dolls -- but the truth is Morton's remarkable life wasn't an elaborate fiction.

He did all this and much more . . . and quite a lot of the time disappeared.

Shadow Morton came up in music the old way, through just doing it and bluffing. There was a part of him wanted to be Phil Spector, another part couldn't give a damn as long as there was bottle close to hand. He wanted to create hit records (and did with astonishing frequency and diversity in the Sixties) but if that wasn't going to happen he would just walk.

He worked in the Brill Building with Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry (right) but got his start out on Long Island when his band the Markeys went into a small studio and recorded Hot Rod in '58 and shopped it to RCA. Morton was 16 . . . but when he left school he just hit the road doing odd jobs.

He worked in the Brill Building with Ellie Greenwich and Jeff Barry (right) but got his start out on Long Island when his band the Markeys went into a small studio and recorded Hot Rod in '58 and shopped it to RCA. Morton was 16 . . . but when he left school he just hit the road doing odd jobs.

When he got back to New York he'd recorded a few songs under other names, and written Only Seventeen for the Beattle-ettes.

With a dollar in his pocket he decided to look up an old school friend who'd had some success in the music game: Greenwich who with her husband Barry had written/produced hits with Phil Spector for the Ronettes, the Crystals and Darlene Love.

Morton promised to write them a hit and came up with Remember Walking in the Sand which was given to the Shangri-Las. It had 14-year old Blly Joel on piano who remembers he didn't get paid.

"He's a pretty strange guy, Shadow," Joel said later. "He's wearing this big cape and dark glases and he played the producer role to the hilt. He talked in these wild dramatic theatrical terms -- he wanted more thunder and more purple on the record."

Morton was on his way but it was to be a stop-start, care passionately/couldn't care-less career which saw him shift from one label to another, one act to the next as he produced them in his own idiosyncratic way.

Morton was on his way but it was to be a stop-start, care passionately/couldn't care-less career which saw him shift from one label to another, one act to the next as he produced them in his own idiosyncratic way.

He thought Iron Butterfly were too tight in the studio (?) so pretended there was some malfunction and told them to just keep jamming. The result was their 17-minute Inna-Gadda-Da-Vida.

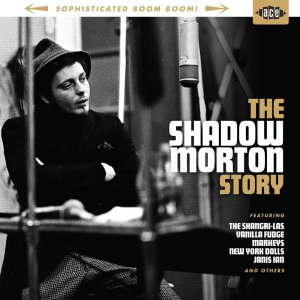

Mick Patrick of Ace Records had a long correspondence with Morton in what were his final years and that is recounted in the considerable liner notes to The Shadow Morton Story (Ace, through Border in New Zealand), a 24 song collection which brings together the Markeys, Beattle-ettes, Shangri-Las and Greenwich songs into the same space as Janis Ian, the Shaggy Boys, Vanilla Fudge, Iron Butterfly, Mott the Hoople and New York Dolls.

It is an astonishingly wayward collection of often melodramatic music, but that was the life and work of Shadow Morton, a man who couldn't play an instrument and once said, "I've never written a song. I write productions. I'm a storyteller. I do soap operas. I'm more a director than a producer".

Actually, even a fiction writer probably couldn't have made George "Shadow" Morton up.

post a comment