Graham Reid | | 3 min read

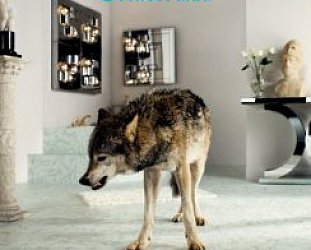

Dave Dobbyn: Harmony House

When producer Sir George Martin died in March, much was made — quite rightly — of his long association with the Beatles. What wasn't made more clear to a couple of generations of people for whom the Beatles are a band from the distant past, was how unusual and almost unique that relationship was.

Martin was there for just about every Beatle record over seven enormously productive years and in many ways enabled them to realise the increasingly complex sounds in their heads.

Today artists change producers regularly, usually to get “other ears” on their music or — as in the case of U2 and Coldplay working with Brian Eno, for example – to push them into new directions.

Over the decades Dave Dobbyn has worked with many producers, among them Bruce Lynch (Loyal), David Long (Available Light), Britain's Adrian Sherwood and Skip McDonald (Anotherland), American Mitchell Froom (Lament for the Numb), Ian Morris (Hopetown) and, in 1995, with Neil Finn for his most interesting, experimental album Twist.

On that album all of Dobbyn's signature styles were there but in the studio Finn and Dobbyn gave them interesting sonic tweaking (Betrayal, Rain on Fire), added unusual instruments (Naked Flame), and they, plus Froom-offsider Tchad Blake were credited with “noise”. It still sprung hits and popular songs in concert (The Lap of the Gods, It Dawned on Me, Language among others) but stood apart for its unusual qualities.

It still stands tall today in Dobbyn's extensive discography.

So it should be no surprise that he has

invited “other ears” in for his new album Harmony House,

this time Samuel Flynn Scott and Luka Buda of the Phoenix Foundation

(and it was mixed by Lee Prebble in his Surgery Studio in

Wellington). In their own way they do what Finn did two decades ago,

just tweak Dobbyn's signature sound and place his voice in new,

different and sometimes quite arresting musical settings.

So it should be no surprise that he has

invited “other ears” in for his new album Harmony House,

this time Samuel Flynn Scott and Luka Buda of the Phoenix Foundation

(and it was mixed by Lee Prebble in his Surgery Studio in

Wellington). In their own way they do what Finn did two decades ago,

just tweak Dobbyn's signature sound and place his voice in new,

different and sometimes quite arresting musical settings.

Harmony House – another in his cleverly ambiguous titles — finds Dobbyn in these uncomfortable times and his songs address this world, the world to come, love and the Lord.

The opener Waiting for a Voice sets the tone immediately. With lyrics about salvation which might have been peeled from Dylan's recent songbook (part narrative, part Biblical vision) which Dobbyn delivers with increasing desperation as the music surges and drives behind him in a wide sonic palette. When Dobbyn lets out a whoop you feel it was probably spontaneous as he was riding the hurricane.

At the other end of the album, the title track which closes things is a hauntingly repetitive rhythm with the lead guitar mixed high and the voices in unison like another piece of the musical landscape, before you notice the whole thing has become thicker and more claustrophobic. Then it ends abruptly, like a release.

Between those points the sound of the album is punctuated by interesting settings (the widescreen Tell the World, the New Wave chug of Ball of Light and lyrics which play off “infidels” and “infidelity”, the gorgeously dreamy submerged sound of Submarine Blue, the home-recording piano of Too Far Gone beneath the embellishments).

It is an album of lyrical darkness'n'light and images from Nature (storms, wind-swept beaches, the fire that cleanses) and his optimistic spirit is tempered by the realities of life . . . yet by the end the journey has been one of hope and enlightenment.

“Sing through the storm and you are halfway to Heaven, my friend,” as he says.

When musicians put their work into the world they lose control over it and others will adopt and adapt it to their own purposes (as happened with Dobbyn's Loyal). Sometimes Dobbyn has put his sentiments to work in way he knows will connect with the spirit of the time (Welcome Home).

Nothing on Harmony House sounds as if it can be beaten into some other purpose, or is as obvious as Welcome Home.

It is a collection of songs which would have been interesting anyway, written by a mature, thoughtful artist who also has a mainline to his pop and rock sensibilities. But he has also been wise enough to let others have an input into how they can be realised and elevated (the gospel choir allusions on the empathetic and reassuring You Get So Lonely).

Back on Twist, Dave Dobbyn

closed the lovely piano ballad I Can't Change My Name. People

of his musical status can't, but he can change the context in which

he places his distinctive songs.

Back on Twist, Dave Dobbyn

closed the lovely piano ballad I Can't Change My Name. People

of his musical status can't, but he can change the context in which

he places his distinctive songs.

With Scott and Buda he has undergone a quiet, subtle reinvention to keep his music fresh (for himself and us) and relevant.

Yet throughout he always sounds like Dave Dobbyn. And, especially given how exceptional this is, you wouldn't have him any other away.

Harmony House is his most consistent and interesting album since, and is perhaps even better than, the terrific Twist . . . which you should also have in your collection.

Evan Silva - Mar 21, 2016

Sounds like a good one ...Evan

SaveRichard V - Mar 21, 2016

Well worth the wait - what happens during a long journey.

Savepost a comment