Graham Reid | | 4 min read

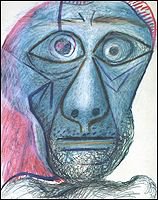

In his last self-portrait -- a crayon on paper work done nine months before his death in 1973, at age 91 -- Pablo Picasso created a disconcerting image: the eyes wide as if terrified, the mouth taut and drawn tightly over the teeth, and the face gaunt with defined cheekbones quite unlike what his bowling ball face actually looked like.

It is a portrait of the man within, the image of a man staring into the abyss of death and considering his life with remorse.

Picasso knew he was to leave a lot of emotional debris in his wake: deaths and divorces, abandoned lovers and children, seductions and suicides, a lifetime of creation and destruction.

"He took the drawing and held it up to his face, then put it down, without any comment," says Arianna Stassinopoulos Huffington, who unsympathetically interpreted an event when Picasso had shown this grim portrait to his friend Pierre Daix.

"It was the face of frozen anguish and primordial horror held next to the mask he had worn for so long and that had fooled so many. It was the horror he had painted and the anguish he had caused and which, in his own anguish, he continued to cause."

Daix, however, interpreted the incident differently: "I had the sudden impression that he was staring at his own death in the face, like a good Spaniard. This was not simple courage, but the courage of his conviction. With the correspondence between his work and his daily life, it was to be expected that the anticipation of his death would assume its place."

A man mortified by his past, or courageously accepting his impending death as the only inevitable in life? Picasso's life and work have never offered themselves up to convenient, unambiguous interpretation.

But what has been long accepted by many writers is that in his latter decades -- and in a life as long as his he had many decades more than most -- his Promethean powers were in decline, his pool of ideas became shallow, his inspiration lacking, his work repetitive or a pale impersonation of what he had once been capable of

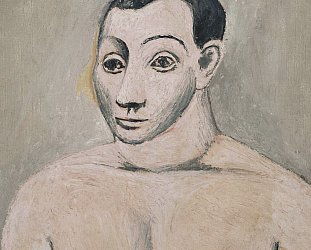

Many critics trace his artistic decline from around 1953 when he was 71 and his 32-year-old partner, Francoise Gilot, left him, taking their 6-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter.

Thereafter the muscular diversity of Picasso's styles was reduced: he painted fewer single outstanding works and favoured serial ideas and reworking motifs across a series of canvases; his sculpture output declined to nothing and he did fewer and fewer ceramics.

Some point to his reworkings of, and homages to, works by Delacroix, Velasquez and Manet - many painted at his Cannes home of La Californie -- as a sign he was bereft of original ideas.

And that while his painterly hand became more free, the painterly quality more fluid, this revealed a decline in technical skills as the vicissitudes of age took their toll.

When Picasso died he had long been consigned to the past, his debut had come 75 years before and the immense influence of his inventions of his Cubist period were all but over by the end of World War I some 55 years earlier. By critical consensus Picasso had no great late-period flourish in the manner of Michelangelo or Matisse.

Yet that opinion isn't quite as clear as it seems. A large and impressive exhibition at Sydney's Art Gallery of New South Wales, Picasso: The Last Decades, not only challenges the consensus but delivers some singular works, among them that scary and alarming final self-portrait.

After Gilot and their children moved out -- prompted by the artist's open affair with the 23-year-old Genevieve Laporte, who subsequently broke off the relationship -- Picasso entered a period of crisis. He was alone at an age when all around him might consider his best years, if not his work, were well behind him.

Yet for the first time he employed a model to pose -- 20-year-old Sylvette David -- and embarked on an immensely productive period. The arrival of Jacqueline Roque in the late 50s also saw him wrestling with his muse and producing some remarkable nudes.

The Sydney exhibition offers many of these in thematically arranged rooms, none more striking than that which holds his graphically sexual etchings of the late 60s, when the old man reflected (often with gynaecological accuracy) on the form of women where there are frequently observers and voyeurs, many the artist himself.

This was the artist outside himself and, as in his earlier portraits of David and Roque, considering the relationship between artist and model as much as reflecting on his sexual experiences.

His series of vivid oils from the same period gathered under the collective title Travesties are playful and penetrating; the images of musketeers, matadors and women are strange conjunctions of limbs and sweeps of vibrant colours. And in his exploration of colour and design -- most evident in The Pigeons of 1956 and his paintings of his studio at La Californie in the same period -- we can see his love of Matisse.

Certainly in an exhibition of this scope -- it covers two decades in almost 100 works -- we can see the signature shorthand, the capitulation to the cliche and draftsmanship only of interest because of the hand behind it. The long-held critical consensus will find support here.

But then there are those outstanding details: the few calligraphy-like lines which create a woman's face in the sensual linocut The Embrace of 1963; the planar quality of Studio at La Californie in 1956 with the tantalisingly empty canvas at its centre; the weirdly kaleidoscopic interpretation of Velasquez' Las Meninas of the following year; the vivid primacy of his consideration of Manet's Le Dejeuner sur l'herbe five years later.

Certainly the final works in this exhibition support the view that the old man lost it at the end. But what an end: in his late 80s still working every day to stare down the death he knew would come.

Certainly the final works in this exhibition support the view that the old man lost it at the end. But what an end: in his late 80s still working every day to stare down the death he knew would come.

Then there is that final, frightening and powerfully moving self-portrait where the realisation cannot be denied or dealt with any longer.

This article first appeared in the New Zealand Herald, February 10, 2003

post a comment