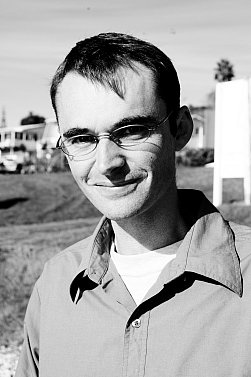

Graham Reid | | 6 min read

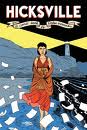

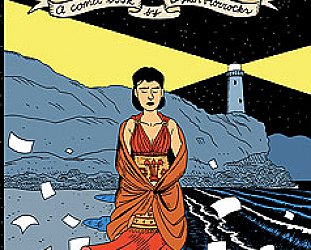

At the launch of the long overdue local publication of his graphic novel

Hicksville in Auckland recently, Dylan Horrocks said he

grew up in two places: In New Zealand and in comics, and both were on

the edge of the ‘real world‘.

“This

was stuff I thought after I finished Hicksville,” he says

later. “It wasn’t like I went in trying

to explain this. But when people started getting me to talk about the

book I realised there was this idea of New Zealand being at the edge

of the world. We’re used to thinking about ourselves that way, at

the bottom, no one pays much attention to us.

“Comics

are similar. In my lifetime they’ve been at the margins of the

literary and art world -- and there is a similar cultural cringe. For

a lot of cartoonists and comics fans there was that same sense of

getting very excited when people from the ‘real world’ take us

seriously -- like when graphic novels started getting reviewed in the

New York Review of Books, the same kind of cultural cringe.

“So

in Hicksville I was trying to get my head around how you deal

with being at that world of the edge, whether it is New Zealand or

comics, which seem like such wonderful, rich, magical places.

“What

I was doing with Hicksville was positioning myself there. I

wasn’t leaving the edge but staying at

the most marginal place I could find in those marginal worlds. That’s

why Hicksville is at the very tip of the East Cape and not on the

maps.

“But

from there I say, ‘this is the centre of

the world’.

“The

planet is not a circle which has geographical centre, it’s a globe

and on its surface there is no centre. Wherever you are on the globe

is the centre of the world. I wanted to see what the world looked

like when I stood exactly at where I felt most comfortable and see

how the rest looks.”

Horrocks

admits Hicksville -- originally serialised in his Pickle

comic between 1992 and 98, and published as a collection by Black Eye

Books in Canada in 98 -- has developed a reputation over the last 10

or so years almost out of proportion to the number of people who had

seen it“.

Horrocks

admits Hicksville -- originally serialised in his Pickle

comic between 1992 and 98, and published as a collection by Black Eye

Books in Canada in 98 -- has developed a reputation over the last 10

or so years almost out of proportion to the number of people who had

seen it“.

“Until

now it was very hard to get hold of. People knew about it but

couldn’t find it. The most common reaction to it now being

published here is, ‘Finally’.

So there is already an audience for it.”

The

complex, multi-layered novel has storylines about comics, Kiwi

culture, the crassness of American capitalism when it sweeps up young

idealistic comic writers and of the smalltown Hicksville where comics

are cherished. Its origins date to when Horrocks was living in London

and feeling homesick.

His

serialisation happened when the first wave of interest in graphic

novels -- spurred on by Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer winning Maus

(86) and Alan Moore’s dystopic Watchmen (87) -- had passed.

Another, less appealing, wave had arrived.

Much

of that comes through in the 250 page book now published -- with an

autobiographical introduction by Horrocks -- through Victoria

University Press.

The

storyline of Todd Burger -- a crass, profiteering comic artist based

in Hollywood -- weaves through the book.

“When

I started I didn’t have a clear sense of

where it was going to go or be about, except it was to do with comics

and small towns and beaches. During that time there was, within

mainstream American commercial comics, a boom driven by speculation,

events like ‘the death of Superman’ and so on to try and convince

everyone, ‘This is collectable‘.”

Horrocks

admits he was “intrigued by was seeing geek cartoonists become

really rich and powerful . . . it was the age of megastars like Todd

McFarlane who left Marvel to start Image comics [in 92] and they were

making huge amounts of money.

“I

thought it was revolting -- mainly because I wasn’t

interested the comics they were doing. For others they were great.

The artists took what the fanboys were interested in, boiled it down

to essentials and beefed those up -- so the muscles were three times

as big. Not my thing at all.”

In

his new introduction to Hicksville Horrocks -- whose first

words were apparently “Donald Duck” -- makes reference to local

antecedents and contemporaries such as Bob Kerr and Stephen

Ballantyne’s Terry and the Gunrunners and Strips

magazine, and concedes his time as an artist for the DC imprint

Vertigo was soul destroying. Drawing Batgirl wasn’t his

thing.

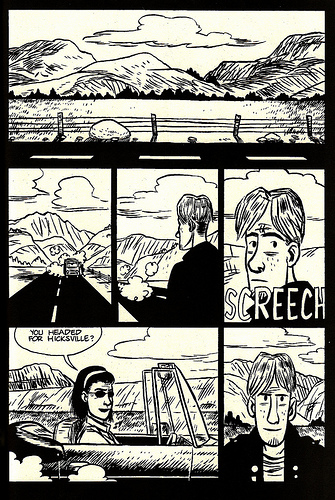

Hicksville

-- in its spare art and complex storyline -- is subtle and often

understated, although it resonates on many levels to different

audiences.

It

is considered a work of post-colonial literature and on the reading

list for such a course at an American university, overseas readers

find the South Pacific location very exotic, but only local audience

will pick up the visual reference to the famous Freeman’s Bay

“Bushells Dairy“.

And

as a character Leonard Batts, described as a journalist and critic

for Comics World magazine, makes his way to mythical

Hicksville he keeps finding pages of a mysterious comic.

“It

is this story of the islands of New Zealand coming adrift and Captain

Cook, Hone Heke and Charles Heaphy trying to work out ,‘Where

the hell are we?’

“I

had no idea where I was going with that image but it haunted me so

much I had to keep exploring it.

“New

Zealand has been going through a dislocated journey of exploration

for quite some time and we almost need a new way of mapping where we

are in the world, but in a way that can take into account constant

change and have a less fixed location.

“We

are no longer in any one place. We’re in the South Pacific but are

part of Asia, Europe, Britain . . . And we have a complex and

interwoven relationship with American culture and society. And

Australia.”

Now

43 and having been making comics since a Gestetner machine at school

through photocopying (“they were a godsend”) and now to the age

of the internet (he posts work in progress and blogs here), Horrocks says he while he majored in

English at Auckland University, “I really majored in comics by

drawing for Craccum”.

He

has seen waves of interest in graphic novels and comics come and go

-- “mainstream publishers wanted their Maus and that lasted

until early 90s, then the bubble burst” -- but feels there has been

a resurgence.

Bookshops

and libraries stock graphic novels, again people beyond the fanboy

base take them seriously, and “a turning point was Chris Ware’s

Jimmy Corrigan in 2000 which won serious literary prizes“.

Horrocks

notes that as with the Maus and Watchmen wave, Ware’s

book did not arrive in isolation for those in the know. Behind the

big names are scores, if not hundreds, of creative people working

away on their projects.

“This

is a much better time to be bringing a graphic novel out.”

And he is. Again. At last.

Dylan Horrocks is the second artist interviewed in the clip below.

post a comment