Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Age has not wearied him -- and nor can it. The little adventurer with a distinctive flick to his forelock, oddly unfashionable plus-fours and rarely a change of clothes, is frozen in time. As he globetrots from the old Orient to the Land of the Pharaohs - and even the Moon - he looks as he ever did. Yet in 2009 he turned 80.

However he is with us still -- and suddenly back in the headlines with the new Steven Spielberg/Peter Jackson film.

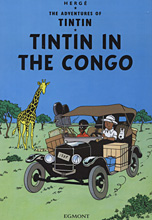

And Tintin has always been news. A decade ago with the publication of Tintin in the Congo, the official British racism watchdog recommended that bookshops across the country remove copies of it. The Commission for Racial Equality (CRE) recommended it be taken off shelves after it received a complaint from a member of the public who had seen it in a branch of the Borders chain of book stores.

"Whichever way you look at it, the content of this book is blatantly racist," the CRE said in a statement. "Highstreet shops, and indeed any shops, ought to think very carefully about whether they ought to be selling and displaying it."

While the book undeniably perpetrated a stereotype there was also been a strong move to remind the public and those taking offense that the book was a product of its period, as Herge himself conceded later in life.

While the book undeniably perpetrated a stereotype there was also been a strong move to remind the public and those taking offense that the book was a product of its period, as Herge himself conceded later in life.

Herge didn't sidestep politics and Tintin books often had a strong social subtext. His first adventure in the Soviet Union was a scouring attack on communism, and Herge intended to follow it with an equally strident comment on capitalism when Tintin went to America.

But Tintin in the Congo appeared instead in 1930, written at the request of his editors to encourage young Belgians to consider a career in the civil service of that colony, now Zaire.

Later he reflected on these first books: "For Tintin in the Congo, as with Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the fact was that I was fed on the prejudices of the bourgeois society in which I moved. It was 1930, I only knew things about these countries that people were relating at the time: Africans were great big children, thank goodness for them that we were there, etc. And I portrayed these Africans according to these criteria, in the purely paternalistic spirit which existed then in Belgium."

Yet despite that controversy Tintin -- with his faithful canine companion Snowy and the accident-prone, dipsomaniac Captain Haddock -- continued to delight, amuse and educate more than three-quarters of a century after his Belgian creator Georges Remi (who wrote under the name Herge) committed him to print on January 10, 1929.

Back then Tintin looked slightly different as he boarded a train for the Soviet Union as a star reporter drawn for a cartoon in Le Petit Vingtieme, the children's supplement of the Belgian Catholic newspaper Le Petit Siecle. The flick of hair didn't come until later when he was accelerating away from the Berlin police in his open-top Mercedes.

In Brussels -- the homeland of Tintin and with a culture of comic book art -- he takes pride of place in the beautifully renovated Art Nouveau building by Victor Horta, the Centre Belge de la Bande Dessine (the Belgian Centre for Comic Strip Art).

Here are the holy relics of Tintin culture: paired umbrellas and bowler hats belonging to Thomson and Thompson; models of Herge's protagonists; dozens of original drawings; and a replica of Herge's desk complete with the detritus of the creator's craft. Down the road off the Grand Place is La Boutique de Tintin selling more of the same: stamps, keyrings and fridge magnets. Anything with his image.

But Tintin is bigger than Brussels, he is global. Tintin books have sold more than 200 million copies -- consistently two million a year, even today -- and have been translated into more than 50 languages including Basque, Serbo-Croatian, Catalan and Esperanto. There are shops selling Tintin memorabilia in places as far flung as London's Covent Garden, Remuera Rd in Auckland, Taipei, Japan (four stores) and South Africa.

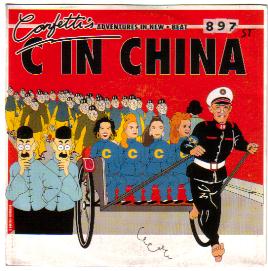

Andy Warhol was a Tintin fan and painted a portrait of Herge. Popular culture is full of Tintin references (viz: the 80s pop band the Thompson Twins, the album cover for the band C ), and flags of the imaginary countries Herge invented appear on otherwise serious websites of national emblems.

There are other websites which use his image to parody political events (China and democracy, the first invasion of Iraq), permanent travelling shows of Herge's art, and for six months in 2004 there was a major Tintin retrospective at, of all places, Britain's National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

There are other websites which use his image to parody political events (China and democracy, the first invasion of Iraq), permanent travelling shows of Herge's art, and for six months in 2004 there was a major Tintin retrospective at, of all places, Britain's National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.

Why there? Well, the grumpy and occasionally pickled Captain Haddock was a seaman so ...

The sponsor of the exhibition -- which had already pulled huge crowds in the Maritime Museum in Paris -- is James Heneage of Ottokar Books, whose company is named for Tintin's 1939 adventure King Ottokar's Sceptre. The director of the National Maritime Museum also noted that Herge drew his vessels -- as he did most things -- with an eye for accuracy.

"The most surprising people love Tintin," the museum's director Roy Clare told the Guardian. "I keep talking to big business figures who get all misty-eyed about Tintin."

So what is the attraction of this little chap who is ostensibly a reporter -- but who clearly has a patient editor and works for a company with a generous travel budget? In large measure it comes down to Herge's clean and accurate drawing.

"I consider my stories as movies. No narration, no descriptions, emphasis is given to images," Herge once said.

His storyboards were simple by current comic book practices (no split images or figures leaping beyond the frame) but in their refinement they never distract from the narrative.

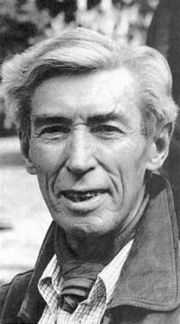

Herge (left) didn't travel until later in life -- when he did his first Tintin the most exciting thing he'd done was go to Scout camp -- but Herge was a perfectionist who studied his subject.

Herge (left) didn't travel until later in life -- when he did his first Tintin the most exciting thing he'd done was go to Scout camp -- but Herge was a perfectionist who studied his subject.

When drawing The Blue Lotus in 1934 he became friends with a Chinese art student, Chang Chong-Chen, who was studying in Brussels and quizzed him for the smallest detail of Chinese costume and culture. Each street sign and wall hanging is accurate, the costumes based on contemporary photographs.

It was his fifth Tintin book, but most consider it his first true masterpiece. The first of many.

Destination Moon -- where the rocket is based on the German V-2 design and Tintin, Snowy, Captain Haddock and the others landed on the Moon 15 years before Neil Armstrong -- is another work of keen observation. Herge studied scientific journals and discussed technology with experts. As a result he accurately rendered pressurised suits and a tank-tracked Moon vehicle.

Even the Yeti, which appears in Tintin in Tibet, was a result of letters and discussions with those who had seen the mysterious tracks or had photographs of the region.

Herge and his hero haven't been without controversy down the decades. Accusations of racial stereotyping have been common and they are difficult to deny when confronted by his Sambo-like Africans -- naive and gullible -- and unflattering caricatures of the Japanese.

Other complaints have been that Herge -- who continued to work for the Brussels paper Le Soir, which was controlled by the Nazis during their occupation of Belgium -- might have been a Nazi sympathiser, an accusation denied by biographers.

But Herge also seemed to possess a strong social conscience, a thread which became increasingly apparent in his work. In Tintin in America (1931) -- a hasty, movie-influenced narrative rush through a continent he hadn't visited -- he includes a brief digression during which Tintin accidentally discovers oil on a Blackfoot reservation. Herge, who was fascinated by and sympathetic toward Native Americans, then has the National Guard pushing the tribe off its land at bayonet-point to allow in oil-hungry developers.

Later other political opinions would infiltrate his work: The Blue Lotus (1934) attacks Japanese imperialism in savage and satirical terms, and King Ottokar's Sceptre (1938) sides with an imaginary European country against the jackboot of fascism.

After the Second World War Herge established a studio of collaborators and by the late 50s he travelled extensively through Europe. In 1971 he went to the United States and met the Sioux in South Dakota. Everywhere, he filled his notebooks with drawings and notes.

Ironically the story Herge was working on when he died in 83 was Tintin et l'Alphe-Art, about modern art, one of his passions, and forgery. Even in its incomplete state it looks to be a social satire on the smart set of film stars and musicians around the edges of the serious art world. There is also a dodgy guru.

In many respects Tintin, a surrogate for the cartoonist's desire for adventure, was the ideal vehicle for Herge's imagination. With no family or back-story he was free to embark on adventures. His nominal job -- only in his first adventure does he file a story -- allowed him to travel to distant and exotic places. And well-intentioned good always triumphs over the caricatures of evil.

In many respects Tintin, a surrogate for the cartoonist's desire for adventure, was the ideal vehicle for Herge's imagination. With no family or back-story he was free to embark on adventures. His nominal job -- only in his first adventure does he file a story -- allowed him to travel to distant and exotic places. And well-intentioned good always triumphs over the caricatures of evil.

For contemporary readers Tintin is also a closed circle. Herge completed 23 books -- typically Tintin was in a tight spot in his unfinished book -- and there have been no "based on" or "inspired by" volumes.

Tintin remains a growth industry -- there has been a television series and now the Peter Jackson/Steven Spielberg movie, and tie-in video game -- and a delight.

He is a timeless boy, the one never ages.

And -- unlike Peter Pan -- he has work to do in this wicked world.

Like the sound of this? Then check out this.

post a comment