Graham Reid | | 4 min read

The legacy of authors is often uncertain. Popular works may fade into obscurity after their death; for others, their words may be elevated beyond the respect they commanded when they lived. Critics say the breadth of work by Maurice Shadbolt is vast but uneven.

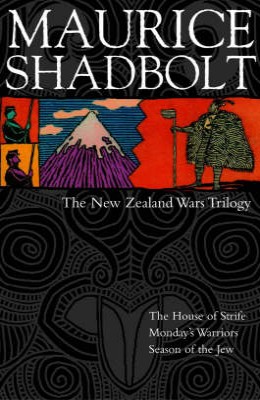

Most agree his trilogy on the New Zealand Wars -- Season of the Jew (1986), Monday's Warriors (1990) and The House of Strife (1993) -- is a significant contribution to New Zealand literature.

"It comes under fire sometimes because it is too much of a Pakeha perspective," says Lawrence Jones, professor emeritus of English at Otago University, "but it is quite an ironic Pakeha perspective. In the long run that will be seen as its strength."

Writer Kevin Ireland says Shadbolt -

who wrote short stories, novels, the play Once on Chunuk Bair, and

two volumes of his autobiography - has left an impressive collection

of fiction ranging across a variety of subjects and involving a

diversity of characters, "but I don't think Maurice spent time

cleaning them up.

Writer Kevin Ireland says Shadbolt -

who wrote short stories, novels, the play Once on Chunuk Bair, and

two volumes of his autobiography - has left an impressive collection

of fiction ranging across a variety of subjects and involving a

diversity of characters, "but I don't think Maurice spent time

cleaning them up.

"Nowhere was that better illustrated than [his 1972 novel] Strangers and Journeys , which should have been his lasting masterpiece.

He took 10 years writing that and in the end simply bundled it up and sent it away. He couldn't face another day with it. And it's a great shame."

Jones says the first part of that novel is "brilliant" when dealing with preceding generations, but when Shadbolt came to his own era, it flies to pieces.

Shadbolt's first collection of short stories, The New Zealanders (1959), was hailed in Britain, where he was living, but criticised at home. Its stories reflected lives in the first half of last century, but subsequently Shadbolt identified himself as being in "an antagonistic reaction" to the provincial puritanism which ran through New Zealand literature.

He grappled with what it meant to live in this land at that time. In 1963 he published Summer Fires and Winter Country, which chronicled the lives of his generation.

"He was trying to deal with a rapidly changing society," says Jones, "and New Zealand was no longer a scarcity society but a consumptionist one. Yet he was most successful when he looked back."

Shadbolt's historical novels are almost universally hailed and critics expect these to have continuing resonance. And he was persuasive when writing of his father's generation, as in Strangers and Journeys.

"He was determined not to work the ground that Frank Sargeson and John Mulgan had cleared," Jones says. "His most outstanding stuff was about the 19th century. There had been sentimental family sagas but no one had dealt with it as critically and originally as he had."

Shadbolt supported his literary career by journalism, which also fed his creative work. "He had a journalist's instinct for getting the story right at the moment the news broke," says Ireland. "He was hot on to the story [military historian] Chris Pugsley had to tell about Gallipoli in Once on Chunuk Bair, and the story James Belich had to tell on the New Zealand wars [in the trilogy]. These will have lasting power."

It is a further irony that the observational eye and sense of immediacy he brought to journalism often failed him in his novels about the contemporary world.

Ireland concedes that a lack of care is evident in many of Shadbolt's novels. "With him, the story was always the thing. That came from his days in country and suburban papers. You had to fill the paper with something interesting and if you got one or two facts wrong you put that down to it being late at night and you had a deadline. But the story was always there."

Author and critic C. K. Stead is diplomatic: "His work was big and bold and rather rough-hewn." Stead admits Shadbolt's work was not to his taste, "any more than I suppose mine was to him". But he felt the writer was a figurehead who proved writing could be a viable career.

"Sargeson had done that ahead of him but Maurice made it possible to support himself and his family by alternating fiction and journalism. He was tremendously courageous and enterprising. He lived a risky life financially but made a go of it, and did this before there was a significant New Zealand publishing industry. He did it partly by finding overseas publishers."

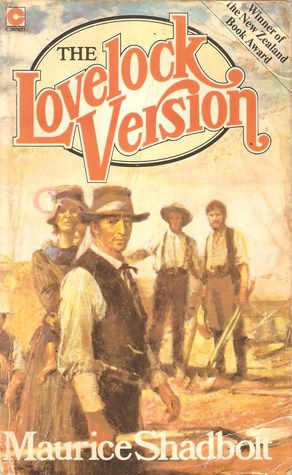

Shadbolt's most complex and

controversial novel was The Lovelock Version of 1980. A muscular

novel with flashes of magic realism which acknowledged Gabriel Garcia

Marquez' One Hundred Years of Solitude and an ambitious reach across

the generations, it also takes jibes at New Zealand history and came

at a time when, as Ireland says, "novel writing was becoming

popular but was a rather morbid exercise.

Shadbolt's most complex and

controversial novel was The Lovelock Version of 1980. A muscular

novel with flashes of magic realism which acknowledged Gabriel Garcia

Marquez' One Hundred Years of Solitude and an ambitious reach across

the generations, it also takes jibes at New Zealand history and came

at a time when, as Ireland says, "novel writing was becoming

popular but was a rather morbid exercise.

"It gets the tone exactly right. It is a homage to our history and a send-up. You have to have supreme confidence to do that. It was the first of his deep historical explorations and deals with pioneering and Maori questions.

"He writes with a confidence which can only be the work of a New Zealand writer who feels himself to be at home in the country with no questions or doubts about identity. It is by a person whose meat and bones are in the soil."

Shadbolt was a popular writer and his major novels sold well. In a small and inward-looking literary community that sometimes counted against him, says Jones.

The private life of the much-married writer may have blurred the assessment of his peers, and time will offer more clarity. Some works may find a new audience in subsequent generations once the details of the writer's life are long forgotten.

Ireland cites An Ear of the Dragon from 1971, which was much criticised for borrowing heavily from papers about the life of its protagonist Renato Amato.

Shadbolt's works were often stylistically innovative if not always successful. He mischievously juggled fiction and non-fiction to ironic effect, told stories through a series of flashbacks, and ran parallel stories of generations and families.

Jones: "In the long run that will look better. He said once he had to set up hoops for himself to jump through. Sometimes the jumping doesn't work, but there were at least a variety of hoops. Once on Chunuk Bair, while it follows his historical interests, is very different from anything else, and it really works."

But as C. K. Stead notes, the writer Martin Amis talks of "Judge Time", and time alone will determine Maurice Shadbolt's legacy.

"Yes," laughs Kevin Ireland. "It's just too soon to tell."

post a comment