Graham Reid | | 9 min read

If you had come here to try to like Fred Durst, frontman and mastermind behind Limp Bizkit, he hasn't given you much reason so far. He turned up for the 5 pm press conference, but then went to look at a house he might buy.

So, there we were: around 20 international journalists flown by his record company to Los Angeles, awaiting his majesty's pleasure for another three hours.

It's a bad start, but neither the unapologetic Durst nor mute Bizkit bassist John Otto, or DJ Lethal who will later blather on about his as-yet unfinished solo album, give indications there's anything unusual in this.

Fred Durst - now 30 but who sometimes reverts to language which is just, like, sooo not mature - is widely considered a fraud by critics who say he sells contrived adolescent angst to teenagers for fun and profit. He writes songs with titles like Break Stuff, but lives in a mansion with a bust of Napoleon on the mantelpiece.

He's on record as saying, "I'm not a rock star, I'm a businessman", and among this self-described social misfit's other jobs are being senior vice-president of Interscope Records and developing movie scripts with Hollywood hotshots like David Fincher, director of Seven and The Fight Club.

Durst is a backwards-cap-wearing former tattooist who can lay down $US3 million ($7.2 million) in cash for a Hollywood home, is a skilled video director and record producer, and counts among his friends George Lucas, Playboy's Hugh Hefner and name players in the hip-hop community like P. Diddy.

For a guy who was briefly in the navy, served a month in jail for assault and was a skateboard punk, he's the living embodiment of the American Dream.

He might consider himself an outsider - he talks of teenage years where he was alienated by whites for his love of Michael Jackson and rap - but this is one non-conformist who prays regularly, doesn't do drugs and has an admirable work ethic.

Such things should be fatal to his street cred with his audience of predominantly testosterone-fuelled boys, but apparently not. Limp Bizkit - bridging metal rock and rap and spawning innumerable imitators - have sold almost 25 million albums.

Critics may write off Durst's songs as trite, calculated and the musical equivalent of professional wrestling, but that doesn't mean you don't want to hear what he's got to say. And Fred has a lot to say this evening in LA, even though there isn't much to talk about.

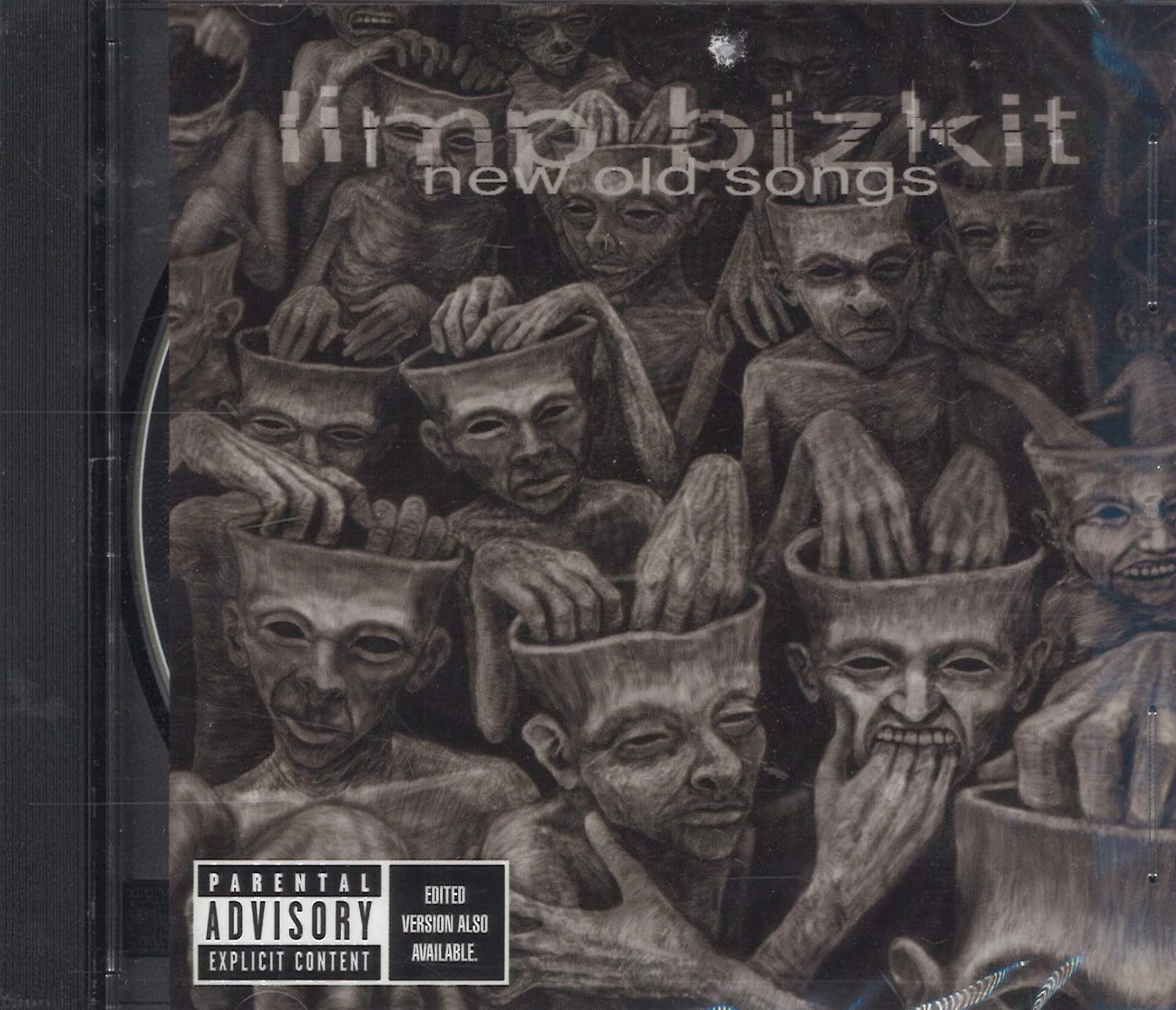

Yes, guitarist Wes Borland has quit the band, but that's hardly a reason for a squadron of journalists racking up frequent flier points. And yes, there's New Old Songs, a remix collection which he concedes is a welcome, coincidental stop-gap while they look for Borland's replacement. But he immediately talks it down. "This is something for anyone who likes bonus or B-side stuff," he says in a likeable drawl, "but isn't something I suggest you get if you want a new Limp Bizkit record. Don't even bother, you'll be disappointed. It's just old songs, different people's interpretations of them, and that's about it."

"This is something for anyone who likes bonus or B-side stuff," he says in a likeable drawl, "but isn't something I suggest you get if you want a new Limp Bizkit record. Don't even bother, you'll be disappointed. It's just old songs, different people's interpretations of them, and that's about it."

Despite Durst's apparent lack of enthusiasm, New Old Songs isn't bad, the result of savvy hip-hop producers such as Timbaland, P. Diddy, the Neptunes and others taking LB songs in another direction. Others include William Orbit and Butch Vig, and by critical consensus the weakest remixes come from Bizkit's Lethal and Durst himself. But in the LB world, if critics don't like it you can start ringing up sales.

"It's a lot more beat and hip-hop orientated but maybe there are rock fans who like Limp Bizkit and if they hear a song they like in one form and then hear it on this new one they might think, 'This is cool'. Or maybe not, I dunno.

"This is not as big a deal as this whole conference suggests. It's so not important. It's just a remix record, man," he says with a shrug, admitting there are a couple of mixes on it he doesn't care for.

It's suggested, given his Interscope commitments, guest spots such as on the recent What's Going On single, movie scripts and so on, that Borland's departure was an opportunity for him to move in a solo direction. But he likes being in a band and views this as "an opportunity to explore and grow and create something on another level without alienating the fans we already have".

He's insistent they won't recruit a name player and Borland's replacement could come from anywhere, even Smalltown USA. It'll be an equal-opportunity for allcomers: "We want to go out with people who wouldn't usually have a chance. We might jam with someone for a couple of minutes, someone might go on the road [with us] for the next four days, it's impossible to tell."

You get the feeling Borland, who occasionally said he felt he was in the wrong band and released a side-project album this year, won't be much missed by Durst.

"The old material is old material and if [the replacement] can't play it, I guess we won't. Maybe what Wes has done will never be played again," he says bluntly, then after a pause adds charitably, "because he's done things so incredible and timeless they don't need to be touched, it doesn't need to be played by someone else."

These are slightly awkward days for Durst: the band in limbo, no new material written, movie projects more a possibility than a reality, and then there's the whole post-September 11 disquiet about violent movies and aggressive music. Their Break Stuff was rapidly pulled from radio.

He believes the anxiety and clampdown is just Hollywood and the media shielding itself from criticism: "Break Stuff is a pretty angst-driven song, but I don't think terrorists are cruising around listening to it. I thought they didn't like music."

He also says some are using the terrorist attacks as a cover for their own activities: "There are a lot of things happening from our own brothers and sisters right under our noses."

This is interesting because more than once Durst suggests he knows things, but can't say. Like, he's connected. He mistrusts the news because, through his FBI agent buddies, he knows "it doesn't tell all," he says, nodding knowingly.

Such as? "I can't tell you; it's not my job."

He definitely believes in UFOs though, but then again Fred believes in "a lot of things that a lot of people are probably opposed to". Again, he won't say what.

This then is enigmatic Fred Durst, the outsider on the inside. He talks of feeling "very emotional" about the band and September 11, of non-specific tensions in his life, and how he suffers anxiety attacks and if you've never had one "you'll never know what it's like to feel like you're dying".

Durst wears these things like a martyr and sometimes a victim. He insists LB don't do things for shock value, but bad luck follows them, like to the Woodstock II festival which went up in flames to their soundtrack. And he obliquely mentions the last Big Day Out in Sydney where a girl was crushed during their set.

"You're at a show and somebody is suffocating in a crowd of thousands of people but you are on stage with sweat staining your eyes and you are feeling the moment. You can't put a radar on and locate it ... They pull someone out and the girl goes to hospital and she dies. You think we want that? We don't create that. That's not what we do."

Perhaps not, but they get mileage out of it. Durst told an American journalist that he visited the girl in hospital. If he did, no doctor or family member saw him there.

If he wonders why some people don't like him, it's because they believe he exploits teenage alienation for his own ends. When he was reported in last week's Entertainment Weekly as saying he'll leave the US for London "because he's sick of the attitude towards [him] in America", the unsympathetic EW added, "Toodles, old chap."

Yes, it's tough living with the contradictions that are the disaffected millionaire Fred Durst.

"I've always been such a closed-up person that I felt like a weirdo for liking the things I liked.

"I've got a few people right now I can talk to, but I don't even talk to them that much. I talk to you [journalists] more than I talk to anybody close to me.

"With the press I give out my soul, little pieces throughout life. I just keep giving this fire inside and it's a way I can feel I'm bonding with everyone and just keep reaching for the fire. It's getting smaller and smaller. I still have a flame left in me and I can only give until I can't give any more. That's what I think that maybe I'm here for."

That sounds difficult, so maybe Durst is just misunderstood? He certainly thinks so.

"Whether I'm a person you like or not I don't care, because I'm being me as well as I can and have a hard time just dealing with my own mind. I think I understand myself, but I don't think it can come out of my mouth in a way for everybody to really know me, and nobody would really care or take the time to look or figure it out until I'm gone.

"I think a lot of people are unsung heroes in that way, and we only took time to figure it when they were gone. I think I'm one of those."

post a comment