Graham Reid | | 11 min read

Jazz trumpeter Miles Davis in his characteristically clipped manner once observed that “the history of jazz can be told in four words: Louis Armstrong – Charlie Parker.”

In offering those two names Davis highlighted two vastly different lives and two facets of genius.

Armstrong was undoubtedly one of the great artists of the 20th century and, although his reputation as an innovator has been tarnished by the perception of him as a mere populariser, there is little argument amongst those who listen that he was a genius.

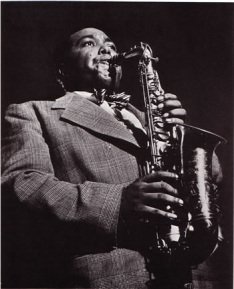

Saxophonist Charlie Parker is the tragic counterpoint. Dead at 34, he had less than half Armstrong’s time and even today his name is little known outside the jazz world.

Yet Parker was, to outsiders at least, the archetypal jazz life – the cinema-screen cliché where the search for new musical forms is lived out in small, ill-lit New York clubs, constantly bedevilled by the mundane nature of life and the debilitating effects of heroin.

This was Parker’s life.

In his introduction to Yehudi Menuhin’s autobiography, Unfinished Journey, writer and critic George Steiner speculated on the nature of genius.

Whereas the ordinary man casts a shadow, says Steiner, the genius casts light.

Yet we often feel that the genius must pay a terrible price for itself.

Yet we often feel that the genius must pay a terrible price for itself.

While that has obviously not been true for either violinist Menuhin or Armstrong, both of whom illustrate charmed and rewarding lives, too often the stories of the gifted ones take turns which can only be described as tragic.

In Parker’s case the genius suffered terribly.

Consider one small fragment of the recorded evidence, two minutes from one of hundreds of recordings, official and otherwise, which feature his playing.

It was 1953 and Parker was sitting in with an orchestra in Washington, the band was playing a lively, if somewhat unspectacular chart and Parker was part of the sax front line.

The tune was called Willis and Parker’s first solo comes in after a slight piano and band flourish.

Parker’s alto saxophone enters the tune with a sharp scattering of notes and then takes off almost sideways through the tune. By the third chorus he is winding up, the notes polished and pure as he forces them upwards, ascending with unpredictable determination until the band members are leaving him to it and shouting encouragement.

Parker is riding the energy, shaping the melody as he simultaneously creates the ideas he hears inside him.

Notes are squeezed atop one another until they almost become an inseparable, turbulent flow...and then, unexpectedly, he pulls back, swoops and sidesteps around the tune once more as the notes sparkle and fly, disappearing like shards of transient golden light.

It is the sound of a man in absolute control of his art, man as the conduit for an elusive muse . . . it is the beautiful but momentary proof of the genius casting light.

Yet this was not flashy self-assertive playing, the arrogance of technical ability submerging restraint.

Consider the circumstances.

Parker had been scheduled to play with The Orchestra, but his behaviour had been so erratic that the concert went unadvertised. The promoters did not want, as had happened often before, an audience to show up expecting to hear Parker and then them having to make embarrassing explanations.

But Parker confounded expectations and turned up, without music and carrying a plastic saxophone.

He stepped up to the bandstand not knowing what tunes would be called. But the band had been told to let him have all the space he needed, to let the man play.

The further irony about this remarkable and spontaneous evening of music is that it was never intended to be released on record. It came out only in the Eighties.

The title of the album was appropriate, One Night in Washington. For despite the genius on display of a kind that other musicians spend a lifetime aspiring to attain, that is what it was to Parker ... just one night in Washington.

The facts of Parker’s life which lead to such extraordinary moments of musicianship are now the subjects of many books, notably those by jazz critic and Village Voice journalist Garry Giddins and the other, more definitive, by Stanley Crouch.

In the acknowledgements to his Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker, Giddins pays a handsome tribute to Crouch, also a Village Voice writer, who in “an unusual if not unprecedented act of scholarly comradeship” made all his research available to him.

In the acknowledgements to his Celebrating Bird: The Triumph of Charlie Parker, Giddins pays a handsome tribute to Crouch, also a Village Voice writer, who in “an unusual if not unprecedented act of scholarly comradeship” made all his research available to him.

Giddins’ enthusiastic comments on the Crouch book whetted the appetite for the study which he called “a milestone in the literature of American music.”

But Giddins’ handsome, extensively illustrated book is, aside from the irritation of a number of typographical errors, an attractive and thoughtful account of the life of the man whom musician Tony Scott said “opened the door, showed the world, and then he shut the door behind him again.”

Much mystery surrounds Parker’s early life.

With an itinerant father and a doting mother, he appears to have been unspectacular at school and in early adolescence – a period of incorrigible truancy marked his last school days, but little else of note.

He showed little interest in music until age 15 and even then was only of middling aptitude.

Yet as with some many musicians – Armstrong in New Orleans, the Beatles in Liverpool -- to cite two obvious examples, the social climate enhanced the opportunities for expression.

Parker was born in Kansas City on August 29, 1920. During the 1930s the city was known as Tom’s Town after ‘city boss’ Tom Pendergast who delivered the Democratic vote through highly suspect political machinations, placed friends in high office with the backing of organised crime and allowed, in fact encouraged, gambling, prostitution and the narcotics trade.

Naturally, night club entertainment thrived and the young Parker was weaned other on the vital jazz sounds of the city.

Pianist Jay McShann reminisced to me about those days in Kansas City.

“They had music piped out in the streets and musicians from all over the country came there,” said McShann when he was in his 70s.

“Any time you find a town as wide open as that all the musicians and pimps and babes move in.”

And like the Beatles in Hamburg and Armstrong in New Orleans, musicians were expected to play long hours and be entertainers – the result was musicians who could improvise at length over standard chord changes.

Into the milieu stepped Parker, a shy and none too talented teenager but one who made up for early humiliations on the bandstand by simply trying harder and mastering his techniques in a number of bands which worked in the circuits outside the city.

He married for the first time at 16 and the following year his erratic behaviour began to manifest itself; he would disappear for weeks at a time began using heroin, but also made enormous strides in his musicianship.

He married for the first time at 16 and the following year his erratic behaviour began to manifest itself; he would disappear for weeks at a time began using heroin, but also made enormous strides in his musicianship.

Band leaders who whom he worked – McShann included – unanimously confirm his reliability and thirst for knowledge. Yet at home things were different.

His young wife Rebecca had to put up with her husband pawning household goods for heroin and lengthy absences as he played the city’s clubs.

But it all ended abruptly when city boss Pendergast was deposed and the city fathers started to clean up the town.

Clubs closed and Parker’s inevitable departure was hastened after a disagreement with a cab driver over a fare the saxophonist couldn’t pay.

Parker knicked the cabbie with a knife, spent time in jail and then hit out for Chicago leaving his wife and new baby behind.

In Chicago and shortly thereafter in New York – where all musicians ended up – Parker blew other musicians off the bandstands in the few opportunities he was allowed as a non-union member.

The return to Kansas City for his father’s funeral put him touch with McShann whose big band was still regularly employed. Parker joined up.

On one tour the McShann car hit a couple of farm chicks and Parker grabbed the “yardbirds” for an evening meal – an action which earned him the nickname Yardbird and later, more simply and eloquently, Bird.

It was in the McShann band that Parker made his name, especially when the group played in New York. His technical ability married with an intuitive stylistic freedom drew the adulation of his peers and eventually he began forming his own line-ups, ironically in the two year recording ban instigated by the musicians’ union to settle a trust fund dispute.

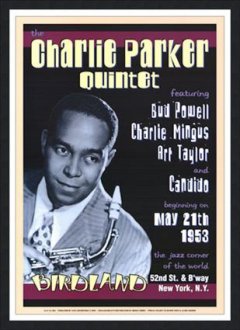

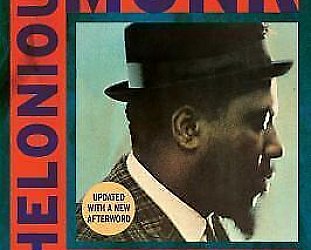

So it was that bebop, the jazz which Parker, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and pianist Thelonious Monk helped to shape, was created in isolation from the larger audience available through recording.

Yet while Parker earned the respect of musicians - Duke Ellington’s trumpeter Cootie Williams calling him “the greatest individual musician that ever lived” – he soured possibilities for himself by his drug dependency.

Agitating to join Count Basie’s band he was finally offered a chance but turned up so dishevelled and later throwing up on stage that the job went elsewhere.

He was fired from McShann’s group for being so strung out on heroin he forgot to wear shoes on stage.

Yet he continued to be employed because of the brilliance of his playing; a few months with the Earl Hines band, a spell back in Kansas City then on to Chicago, back again to New York and off to St Louis before returning to New York...in each place sitting in with a different group.

But it was the teaming of Parker with Dizzy Gillespie that was the watershed – for the artists, for the music and for the era.

They created a free flowing spontaneous sound which had no precedent and caught the mood of the post-war era. It was celebratory music yet serious, liberating but intense ... and Parker was still only 24.

He played wherever he could, at least as often as his heroin habit allowed, and began to record regularly, most often as a sideman.

At the end of 1945 he signed with the Savoy label, recording his seminal sessions.

At the end of 1945 he signed with the Savoy label, recording his seminal sessions.

Then it was off to Los Angeles and a period of addiction crisis – and imprisonment for six months.

Yet at all times Parker’s curiously ambiguous personality allowed for recordings of his genius, in Los Angeles on the tiny Dial label.

On release from prison he recorded, and was recorded privately by fans.

Despite his best efforts and constantly telling others that he played best when not using drugs, he returned to his heroin habit and erratic behaviour.

His second marriage, to Chan, suffered and although he played, recorded and was a legend amongst his fellow musicians and an adoring audience he was sniffed at by critics or worse – ignored.

In that regard posterity has served Parker rather better than his life did.

Parker was hurt by the ignominy of neglect.

When Life magazine ran an article on bebop which he had helped define Parker wasn’t even discussed. Even more insulting to him was when Time Magazine ran a cover story on the new jazz it picked the white, conservative figure of college favourite Dave Brubeck to focus on. These thing wounded Parker deeply and worse, he dwelt on them. He also became frustrated by what he felt were his own musical limitations.

Always passionate about Prokofiev and classical music, he approached the composer Varese during a European tour and asked to be taken on as a student.

He recorded an unsatisfactory, but ironically very popular, album with strings in the hope of bringing his classical ideas together.

But his time was running out.

His cabaret licence was revoked and for nearly two years he was unable to work. He was banned from Birdland, the New York club which had been renamed in his honour only five years before. He recorded with artists unequal to his stature...and the things kept getting worse.

His two-year-old daughter died and his relationship with Chan, always shaky began to sour. He tried to commit suicide and was checked into Bellevue Hospital. After 10 days he was discharged but returned voluntarily.

His death on Saturday, March 12, 1955 came at the end of months of decline during which he continued to play, often in small clubs with inadequate sidemen.

That weekend the legend “Bird Lives” started appearing on walls in Greenwich Village.

Today, nearly six decades after his death, it matters little that he was buried in Kansas City despite his request not to be. Nor that his tombstone carried the wrong date or that his passing was barely noted in newspapers of the day.

Today, nearly six decades after his death, it matters little that he was buried in Kansas City despite his request not to be. Nor that his tombstone carried the wrong date or that his passing was barely noted in newspapers of the day.

None of that is important.

The slivers of genius capture on a hundred recordings, the sparks of music flying into a darkened club . . . those are the things which last.

And whenever musicians, jazz players or otherwise, listen to the warm beauty of Charlie Parker then pick up their instrument to play, the yearning invocation is made again. A few shards of reflected light.

And Bird lives.

mark robinson - Mar 27, 2011

Ross Russell's Bird Lives remains my favorite Charlie Parker book but I might check this one out. ABC showed a very interesting doco last week on Pannonica de Koenigswarter - http://www.spinner.com/2009/11/25/monk-and-the-baroness-an-interview-with-documentarian-hannah-ro/

Savepost a comment