Graham Reid | | 12 min read

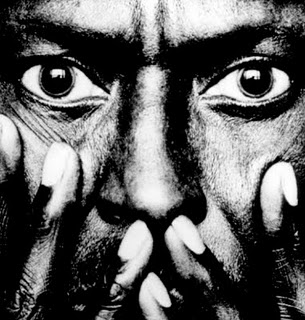

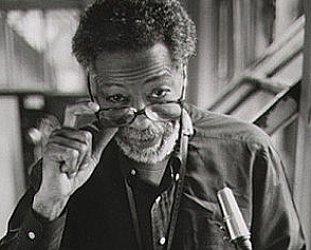

It was probably about lunchtime in New York, but here in Auckland it was 4.30 am on a grim and watery Tuesday, hardly the best time to do a phone interview. Certainly not this prearranged caller to the man known as the Prince of Darkness and who has been known to open his end of the conversation with a terse “Don’t ask me no stupid questions man.”

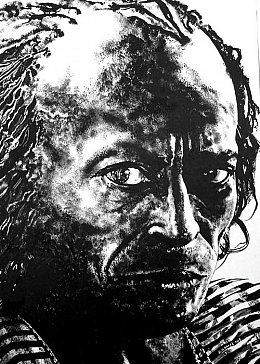

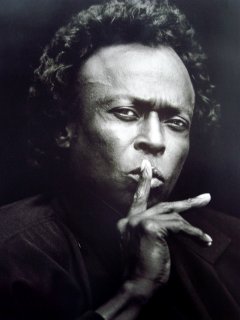

But with a quick press of a 13-digit number he’s there – trumpeter Miles Davis sounding as wheezing and croaky as legend has it. In the world of contemporary music – he long since left the tag “jazz” way behind – Davis is the man who has consistently sought new methods of expression and seldom looked back at what he’s left behind.

So the place to start with Davis is here and now. And for us the now is his new album Siesta.

"Siesta? What?"

The disembodied voice wheezers on the end of the phone: “What? What’s that, man?” . There is a long pause followed by coughing, and the voice comes back: “What the fuck you talkin’ about?”

Another attempt and a clarification: “The album you did with Marcus Miller, the soundtrack to Siesta.”

“You askin’ about Marcus?” Another long pause: “I don’t know you’re talkin’ about now.....can you call me back, maybe in a couple of hours, I just ....”

Two hours gives a lot of time to reconsider the career of Miles Dewey Davis who, at least three times, revolutionised jazz but for some time has only recognised the label “Miles Music” for what he does.

“Don’t call it jazz man,” he barks threateningly at anyone who would be so foolish.

Davis is tough and always has been. Tough on musicians and critics but also tough on himself.

At 61 he is working with musicians half his age and outstripping them more often than not.

He played with Charlie Parker in the 40s, formed what many regard as the classic jazz quintet with tenor saxist John Coltrane in the 50s, formed another classic group of Tony Williams (drums), Ron Carter (bass), Wayne Shorter (sax) and Herbie Hancock (piano) in the 60s, and almost single-handedly invented the fusion of rock and jazz in the 70s.

These days he swaps tapes with Prince.

On the way he recorded albums like Kind of Blue, a sort of Astral Weeks in the jazz world which demands you come to terms with it before you undertake much more the influential albums Porgy and Bess. Sketches of Spain and Miles Ahead with arranger Gil Evans, and always confounded his audiences with his innovation and audacity.

In 1944 Davis enrolled at the Julliard School of Music in New York. He had already been playing trumpet for five years in East St Louis, had listened to Clark Terry and Buddy Anson and fallen under the spell of saxophone player Charlie Parker.

It was Parker he roomed with in New York and before he was 20 he was playing in clubs on 52nd St and recording with Parker. By late ’48 he had formed a jazz orchestra, met arranger Gil Evans and in early ’49 took the band into the studio to record the first tracks for The Birth of the Cool, an album which reshaped the way people heard jazz.

Since then Davis has rarely been out of sight. His fusion of jazz and rock in the early 70s on Bitches Brew baffled older fans and led the Encyclopaedia of Jazz to note in 1978 that after the electric album In a Silent Way “Davis subsequent output is of little interest to the jazz record collector.”

In the mid 70s Davis retired briefly when a number of illnesses overtook him.

In ’81 he came back with a funky rock album Man With the Horn. His long-time record company Columbia had T-shirts made with the line “Music is Measured in Miles,” and while that had long since ceased to be true, Davis still managed to show over the next few years his ability to keep people listening.

Few of the albums have been great but they’ve never been uninteresting. Cyndi Lauper, Scritti Politti and Michael Jackson tunes have all been fair game for Davis lately.

Before his successful Tutu album of ’86, Davis split with Columbia and his second album with new label Warners which like Tutu he recorded with young studio wizard Marcus Miller, is Siesta, the soundtrack album he seemed to deny knowledge of in this early morning phone call.

The phone rings and he’s back, the voice as strained as before but he’s happy to talk, and unexpectedly apologetic: “Sorry man. I was sleeping before.”

The first thing he wants to do is place his relationship with Miller into perspective.

“Let me tell you about Marcus,” he says patiently, as if anticipating yet another suggestion that Miller has usurped him. “Marcus only does what I tell him to do. We work together like Gil Evans and I used to do. Marcus is an arranger like Gil was, and a composer.

“There shouldn’t be too much emphasis on how he does this or that. Some people can do it, some can’t. I can’t do it. I think too much. I get one melody and a hundred thousand come into my head. I’d be forever changing, so I like to work with someone else like Marcus or Prince or Jimmy Jam and Terry.

“I mean, I bounce off people and they bounce off me. I give Marcus ideas and he gives me ideas. You can’t live alone. It’s like Vladimir Horowitz, he doesn’t write his own things and if he didn’t have the composers he wouldn’t have nothin’ to play.”

He laughs so hoarsely the voice disappears.

Most recently Davis has been in touch with Prince and his Minnesota music machine.

According to one story, Prince sent Davis a vocal and instrumental version of a song entitled Can I Play With You and a note saying he understood what Davis was doing because they thought alike. Davis apparently recorded a part, added it to Prince’s and returned it.

“Actually he sent me five tracks,” says Davis, laughing again. “Last time we were in Europe we did them for radio and television but we haven’t been into the studio to record them.

“I love the way Prince writes with all that space. He writes these two-bar phrases and then leaves openings – and he doesn’t use the bass, which is great. I like those short phrases like one would do on a commercial. Prince also plays drums, so he knows where things are going to fit in the puzzle.”

He warms to the subject of song writing and although he admits he doesn’t do much himself, he is under no doubt about his individual style.

“I just started writing but the way I do it I don’t repeat anything. I just write about six compositions, we might play three or four of them in New Zealand. They don’t repeat anything but the rhythm, which is a great way to write. The band just love it. Prince writes like that too because he can write behind the singer. The singer would do something and he’ll let the rhythm finish it.

“But the thing is, I wrote something for the band and now I can’t stand anything else we play.”

Those who have seen the new young line-up Davis is working with are evenly divided in their opinions, some saying the hard funk groove is a masterful combination for Davis to play over, others writing it off as insubstantial and a combination unworthy of Davis’ still extraordinary talents.

The band he is bringing here is essentially the same as that he toured with in Europe, with a couple of exceptions. Bassist Darryl Jones has been replaced by Benny Rietveld and percussionist Rudy Bird’s place is taken by Marilyn Mazur.

It’s a young group and an unusual line-up drawn from very different backgrounds. Keyboard player Bobby Irving came over from the production side (Sister Sledge and Ramsey Lewis) and hadn’t worked much on synthesisers until he met Davis in 1980.

Adam Holzman, also on synthesizers, was in rock bands until Davis heard one of his demo tapes and hooked him in for his ’81 comeback album The Man with the Horn. Sax and flute player Kenny Garrett worked with Woody Shaw, and drummer Ricky Weldman was a club player in Washington DC.

The mystery element is the guitarist Joseph Foley McCreary, who simply goes by the name Foley and plays a four-string guitar.

“It’s not a bass,” says Davis. “It has four strings but it still sounds like a guitar.”

Until recently the bassist was Darryl Jones who worked on Sting’s Dream of the Blue Turtles album and toured with the former Police frontman.

Davis enjoys working with the younger players.

“The reason they look so young is I’m so old. Coleman Hawkins told me years ago never to work with anyone my own age; it’s so hard to break their bad habits. But even the young ones can be trouble you know.

“I had a lot of trouble with Darryl after he left Sting. I just wanted him to play, and then shut up for two bars, but he’d always play in the space. Finally I told him I was getting another bass player – and I love Darryl – but I had to get another bass player because he wouldn’t shut up.

“Instead of going forward he was going backwards. I told him not to lose what he brought from Chicago, but some guys just go backwards, man.”

Backwards and forwards are relative terms but no one could accuse Davis of standing still. He listens to a good cross-section of music but when pushed for his current listening he cites only contemporary black artists like those on Soul Train. Davis has always been contemporary in his tastes.

At one time he was keen to work with Jimi Hendrix.

“They asked me to make him up to date,” he laughs, “but he never did have any melodies so how are you going to record something like that.”

As recent years have shown in the cover of Cyndi Lauper and Michael Jackson tunes, he has always going his own way. His departure from Columbia Records after a long association was over a Lauper tune, yet ironically both Davis and the company wanted it released.

“CBS didn’t release Time After Time when it was supposed to. Every time I’d play it people would applaud and George Butler (of CBS) said, ‘Why don’t you record it?’ I told him I already had.

“Then three months later he heard me play it at the Montreux Jazz Festival and said again I had to get it out. After a year they still didn’t get it out so I said that’s it.”

Another problem at the time concerned a Davis tribute album by Danish composer Palle Mikkelborg on which Davis played: “The record company wouldn’t pay for the last digital tape we had to do in Copenhagen so I had to use money from the National Endowment of the Arts to finish it. “

So after 30 years with the company, Davis quit. Yet there were more than these incidents, Davis suggests. The company had an up-and-coming young star on its books, Wynton Marsalis, the man touted in some circles as the New Miles.

“George was always calling me up about things. One time he said, ‘Miles, why don’t you ring Wynton?’ and I said, ‘What for?’ He says to me, ‘It’s his birthday.’

“I knew then I had to get away from those motherfuckers [CBS]. That was the only way they could get some publicity for Wynton I think.”

The Wynton versus Miles stories are as common as they are false. Davis expresses no antipathy to the young star and when he was in New Zealand recently, Marsalis wouldn’t be drawn on Davis either.

“Wynton called me the other day and wanted to come over and talk about how he was tired of playing classical music,” said Davis. “He said it was too confining and I told him I knew that – that’s why I stopped.”

But if he keeps his opinions of Marsalis close to himself, he lets fly an unsolicited tirade against the recent Grammy Awards and by extension the inherent racism he sees in it.

“At those Grammies Jackie Mason, a Jewish comic, got up and spoke for 10 minutes and had bad black jokes and was looking at Quincy Jones. And you know, they wouldn’t let us play for just one minute.

“I watched the show and it was terrible. David Sanborn and Michael what’s his name – Brecker? They played Tutu and tried to outblow each other by playing fast and loud. It killed the whole piece. That composition is a soft piece,” he says in disbelief and frustration.

His anger starts to come down the narrow phone line and he continues in increasing rage: “Then I read in the paper Sting won the best jazz group award.

“Now, when they ask me if the audience is still prejudiced, I say ‘yes.’ It’s never stopped. In fact it’s worse.

“How the hell is Sting going to win that award when he’s a singer. That band just do nothing. But you see what the white man can do. He just says to hell with the laws of nature.

“I hate that and that’s the reason I speak out. When all of us are gone they’re going to say in 1988 Sting won the best jazz band award. That’s what history will read. But wasn’t Miles Davis playing then? Wasn’t Wynton Marsalis playing then? Wasn’t Herbie [Hancock]?”

If Davis sounds angry with Sting, he makes it clear that he considers Sting honest in what he does.

“He does it for himself, it’s what he feels. But for critics to vote for him as best jazz band, that’s crazy.”

It’s interesting to note Davis includes himself in the list of characters playing at the time Sting wins best jazz band award after so long denying the word ‘jazz’ in relation to what he does.

He laughs again.

“Wynton’s the one who likes to use that word. I never use it.”

But there was a time when Davis was a jazz musician; a lot of the recordings from that period are still in vaults at CBS. Recently CBS started releasing some of that material, sometimes simultaneous with music in his Miles Music style. At the time he expressed anger at it. Now it doesn’t seem to worry him.

“There’s no bad material in there so I don’t care what they do. You must remember all art is only a style and music is only a style made up of different styles. The only real music lover I knew was Gil Evans.

“He would call me up and say, ‘Miles, if you’re ever depressed listen to Springsville on Miles Ahead.’ He’d call me up any time of the day or night and say ‘Gee, did you hear that chord Prince played on such and such a thing that was really beautiful.’ Gil had a mind like a computer. He loved all types of music.”

Evans, who died only 10 days before this conversation, is much on Davis’ mind and even when asked about his recent film, television and video roles he returns to the subject. Outside his own videos the trumpeter appeared on with the funk band Cameo which, unknown to Davis, was led by the son of Lee Blackmon – “a fight trainer who used to show me dirty tricks in the gym” – and he has appeared in a recent episode of Miami Vice, and in a new Bill Murray film.

“I was also on Crime Story and another pilot for a series where I played a black gang leader in a wheelchair.

“But doing that is the same as making music. You just get into somebody else. When I write for my band I have to get into the head of my guitar player Foley. I’m another person. And when I write like Gil Evans, I’m Gil. There’s no difference.”

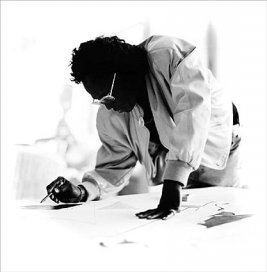

These days Davis is not only writing for the band, making videos and touring, he is an enthusiastic artist who carries a sketchbook everywhere and he has become something of a collector.

“You should get some young artists’ work together so I can buy some. I do a lot myself, you know. I’m having a showing in Madrid in May and another in Munich. I’m gonna have one maybe in Los Angeles, too.”

But talk about art and horses – “You got horses in New Zealand? I gotta to see some of them” – diverts from the real issues, his music. And the unanswered questions about Siesta.

Asked to pick out albums he’d recommend to anyone coming to the awesome Miles Davis catalogue of more than 40 albums in different styles, he laughs again.

“I’d say Tutu and the next one I’m gonna make.”

And Siesta? The album with Marcus Miller, the soundtrack?

“Oh, I’d forgotten all about that. That was so long ago. We started that last year about March or April. But that’s only a style. You just explain to everyone Siesta is only a style, and we do have some new music because a lot of the music we play I don’t record.

“You tell everyone they’ll hear something they like.”

For an in-depth review of Miles Davis' subsequent concert in Auckland in 1988 see here.

mark - Sep 20, 2010

I was travelling in Malaysia when Miles died on September 28 1991. I had been on the island of Langkawi for a couple of weeks, just relaxing and contemplating life. On the trip back to the mainland there was a newspaper that was a few days old. Only a few pages of the paper remained and one of them carried the report of Miles' death. It is one of those moments that has stuck in my mind to this day almost 20 years later

Savepost a comment