Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Aretha Franklin: When the Battle is Over

When American critic Dave Marsh complied his The Heart of Rock and Soul in the early 90s -- a free-swinging personal recount of the “1001 greatest singles ever made” from doo-wop Moondogs (1955) to dance floor Madonna (1985) -- one name turned up repeatedly.

For those who nostalgically put Abba up the charts again (and again) that name may seem surprising -- but here was someone whose “greatest singles” count was pipped only by Elvis, James Brown and Marvin Gaye.

More classic singles than the Stones, Springsteen, Elton . . . and Abba?

It could only be the Queen of Soul, Aretha Franklin.

For the past few decades Aretha hasn’t kicked up quite the same dust she once did, although ironically her first platinum album didn’t come until Who’s Zoomin’ Who? in ‘85, and that is over 20 years ago now.

But with Respect in 67 Franklin -- who turned 66 this year -- staked her claim to the Queen of Soul title and its telling that none of her innumerable followers (Natalie, Aretha’s god-daughter Whitney, Mariah et al), many of them bigger sellers but lesser talents, have attempted to claim it from her.

None could, because the forces which shaped Franklin were unique and impossible to replicate anymore.

Franklin was a child of the church. Her father the Reverend CL Franklin was a high-profile, somewhat flashy and extremely popular Baptist preacher who counted Martin Luther King, Jesse Jackson and numerous soul, gospel and jazz musicians among his friends and peers.

Aretha toured the circuit with him and when they settled in Detroit (the home of Motown) he encouraged her to take the church to the street. Aretha knew the spirit -- and sex.

At 17 she was already a mother of two and in the tradition of Ray Charles intuitively secularised the gospel spirit.

In the early 60s she recorded a dozen or so albums for Columbia but really hit her stride when she signed with producer Jerry Wexler at Atlantic in 67.

He teamed her up with a black’n’white band and arranger Arif Mardin and let her get back on piano.

She had five top 10 hits in 67 alone and on her first Atlantic album, I Never Loved A Man The Way I Loved You, served up such undiluted greatness that virtually every track appeared on the four-CD box set Queen of Soul; the Atlantic Recordings released in the mid 90s.

The church gave her the spirit, the times gave her the context and the Columbia years had taught her how to use a studio.

And, as Marsh points out, with her politicised reworking of Marvin Gaye’s Respect and the Goffin/King/Wexler-penned (You Make Me Feel) Like A Natural Born Woman she touched two sides of the female equation. Respect is a celebration and demand for equality and independence, Natural Woman is about the magic of mutual sexual excitement.

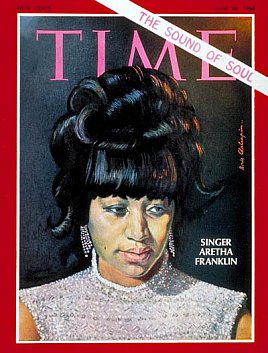

Those parameters in place, Franklin was free to go anywhere. She became the personification of the new black woman and in 68 she was the first black woman to be on the cover of Time. That same year, as an avid follower of Dr King, she sang at his funeral Precious Lord, the gospel song she sang as a child and first recorded at the age of 14 in her father’s church.

Yet as Marsh also points out in the booklet of essays, discography and reflections that accompanied the 86-track Queen of Soul collection, her title does her a disservice because it implies she conquered only one section of the musical universe -- whereas she in fact reigned over “every kind of vocal vernacular of her time”.

She may have been tetchy, reclusive, surly even . . . but as always the evidence is in the grooves, and if the first of the four discs in that set speaks for itself through its classic titles (Chain of Fools, Respect, Ain’t No Way and others in Marsh’s “greatest singles” list) what follows on the other three discs is evidence of the breadth of her talents.

A great singles artist she may have been, but it was on her albums -- and especially live ones such as the classic Aretha in Paris in late 68 -- that she shone brightest.

On The House That Jack Built she’s a Southern soul shouter, Night Time is The Right Time mixes gospel and sex, and Rock Steady is pure James Brown funk.

At the piano she could thump like Nina Simone or tickle like the most subtle of jazz players. She is contemplative and sublime on Spirit in the Dark (with Ray Charles) and git-down-wit-it on Try Mattys.

And -- like Otis Redding -- she could also recast pop hits of her day and stake some claim to them: she adds an edge of desperation to I Say A Little Prayer, finds the spiritual centre of Bridge Over Troubled Water and Let It Be, swings up on Sam Cooke’s You Send Me in a light Motown style, and takes the Motown right out of Tracks of My Tears turning it into a Caribbean lament.

Eleanor Rigby picks up the rice in a Southern Baptist church.

By the end of her tenure at Atlantic in the mid-70s she wasn’t quite in touch with the same heart however. She did a grand tour of producers such as Quincy Jones, Lamont Dozier and Curtis Mayfield, but they weren’t working out for her.

Things weren’t the same after that. Albums such as Aretha ( her first for Arista in 1980) and Zoomin’ contained essential statements and she occasionally records the most inspired soul gospel.

But during the late 80s the world of black/women/politics changed and Aretha was older too.

She has done career-propping duets (George Benson, George Michael with Annier Lennox) and deservedly appeared on the soundtrack to Spike Lee’s film Malcolm X singing Someday We’ll All Be Free. But these days she’s perhaps most familiar for her cameo spots in The Blues Brothers movies which are reminders of who she was.

When she teamed up with Lennox she was testimony to a sister who had done it for herself.

It was the early Atlantic years when she consistently produced work of earthiness, elegance, stature and spirit.

During those years she threw out great singles, recorded one of the all-time classic live albums (regrettably only one track from Aretha in Paris made it into the Queen of Soul collection), picked up 20 Grammies, put the spirit in the street and took pop music down to the river.

She became the Queen of Soul.

And then some.

post a comment