Graham Reid | | 3 min read

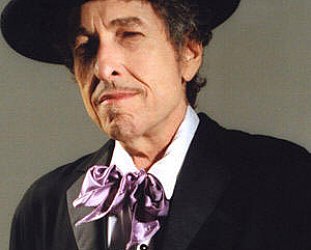

Blame Dylan for box sets. It was his Biograph in November ’85 (16 unreleased tracks among the 53 spread across five albums, later three CDs) which began things by reaching 33 on the American charts.

Sure, there had been box sets before – but mostly for dead guys.

Dylan and CDs together proved there was money in this market. Then his spectacular Bootleg Series in 91 set a new threshold (58 previously unreleased or rare recordings, whew!)

But there’s a big difference between Dylan’s offerings and, say, Aerosmith unleashing Pandora’s Box - 31 previously released tracks, 21 unreleased but mostly indifferent things collected from their sub-Stones years.

Some recent sets have had great historical significance (the Robert Johnson and Bessie Smith Complete Recordings), others are useful collections of diverse or scattered material (the Phil Spector Back to Mono collection) and yet others force some re-evaluation of a body of work (the Byrds and Rod Stewart sets).

Others are just lumpen masses of product (the Elton John crate and the ill-balanced Jeff Beck set).

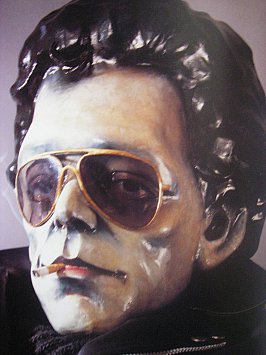

After his cracking New York, Songs for Drella (with John Cale) and Magic and Loss albums, by the early 90s Lou Reed was ripe for an intelligent, revelatory retrospective. It might seem like a marketing decision but Between Thought and Expression, a three-CD set, was being talked about three years ago when compiler John Snyder (a man of rare integrity in the Bizness) was speaking enthusiastically about all the unreleased Lou material available.

A complete live concert would make up one disc, he said.

Well, something happened along the way Snyder fell out of the picture and Lou enters himself to take charge ... and, as everybody knows, Lou is a control freak.

Interviewers at the time were told they not only need to be very familiar with Magic and Loss, but may even be subjected to spot quizzes on the lyrics. Some fun, huh?

So with his box set Lou presented himself and while it is still true, as he once said, that “no one does Lou Reed between than Lou Reed,” you cannot help but feel another hand on the helm might have helped with this retrospective, which was determinedly subtitled The Lou Reed Anthology. Note that definite article there, prospective anthologisers.

First – and most disappointing – there are only five previously unreleased tracks among the 45 collected (plus a few hard-to-find but hardly essential items). Long-time fans are not getting any particular rewards by investing in this package.

And what happened to the stuff Snyder was talking about? And all the other fascinating-sounding things that co-compiler Rob Bowman writes about in the extensive bio in the accompanying booklet? The other take of The Gun on which Lou “just went too far”?

Some pre-Velvet Underground stuff?

The VU have long had their own box set, so none of that appears here. But material deleted from Reed’s original double-album conception for the Berlin album?

It ain’t here either, folks.

In that light, Between Thought and Expression can be seen as both a lost opportunity and an artist keen to rewrite or keep tight control of his own history.

These days Lou has rock poet laureate status and seems not to want to remind himself of, say, the lunk-headed but honestly screwy Take No Prisoners live album where he seemed to want to be a tough, Denis Leary-type stand-up. (One of the unreleased tracks is in the box however, the unmemorable Here Comes the Bride from the same ’78 concerts which even he dismissed as “a fun song”).

This is not to say the box isn’t worthy in itself, although Reed aficionados could, with some justification, bemoan the absence of spoken-word things such as Families and The Day John Kennedy Died or the grim parody of I Wanna Be Black.

Of the previously unreleased tracks, the 12-minute live Heroin with trumpeter Don Cherry is the standout; Cherry’s stoned trumpet and Michael Fonfara’s vibe-like keyboards set up Reed for an agonisingly intense slow version.

The ’75 version of Downtown Dirt (which later appeared as Dirt on the ’78 album Street Hassle) is a beauty too – quietly venomous with Reed at his reptilian best. But Bowman writes enticingly of a desperately intense nine-minute take of the same song, too. Hmmm.

All that said, the many faces of Lou Reed to that point are more than adequately represented. There are the well-known songs (Wild Side, Vicious, Street Hassle) and the rock’n’roll animal unleashed (Waves of Fear, the live Sweet Jane from ’73). There are a few soundscapes (The Bells sounding no more penetrable for its remastering, and a 90-second snippet from Metal Machine Music) and Reed’s poetic inclinations (My House).

Reed’s chronological compilation ambles effortlessly from him in street-pop bent-balladeer mode (Satellite of Love) to teetering junkie (How Do You Think It Feels).

There are also the other sides of his persona: the not entirely cynical Little Sister and Teach the Gifted Children. And he reminds us that, like John Lennon and Neil Young, he is an underrated primitive guitar player in tracks from that Blue Mask period where he played off ex-Voidoid Robert Quine.

For the consistency of his vision (Caroline Says, from ’73 isn’t that far from New York or Drella), his sheer wilfulness and graduation from heroin to hero, Lou Reed undoubtedly deserved a retrospective box set, particularly at that time.

But you can’t help think his audience(s) deserved a more thorough one than this.

As a collection it’s probably a three star thing but, hey! This is Lou, man.

Like, you know, the legendary heart, the one who finally didn’t play football for the coach. That is always going to be worth more than mere stars anyway.

post a comment