Graham Reid | | 8 min read

Kronos Quartet: Lonely Woman (by Ornette Coleman)

When David Harrington hit the stage it was with a lot of style. Wearing a lurex T-shirt, leather pants and ankle boots, and a tight black jacket he looked every inch the lean and rangy musician blowing into town for a couple of concerts.

Beside him was the group, also all in stylish black attire. And they were greeted with rapturous applause.

Some in the capacity crowd which filled Wellington’s State Opera House would be recalling the previous day’s blistering version of Jimi Hendrix’ Purple Haze, others the soaring Ornette Coleman blues.

They were hip and they were hot, edgy and intense.

The irony was that the band in black, “The New Fab Four” as Rolling Stone magazine called them in a direct reference to the Beatles, was not a rock outfit at all but a string quartet out of San Francisco, a band which is causing big ripples in the classical world.

Within the bow-tie and tuxedo set there are a few sceptics but certain facts speak for themselves.

The group’s latest album White Man Sleeps was nominated for a Grammy and the previous one - with the Hendrix track nestling alongside exciting pieces by the Australian composer Peter Sculthorpe and Finish composer Aulis Sallinen - sat in the top 20 of Billboard’s classical charts for more than 40 weeks.

For David Harrington and the other members of the Kronos Quartet, such successes as they are enjoying now have not come easily. Their overnight fame was 10 years in the making.

The Kronos Quartet has been Harrington’s vision from as far back as 1973 when he brought together the first line-up with a view to playing music exclusively of the 20th century and, where possible, work by living composers.

“I had the conception but none of the music,” he smiles, “because none of it had been written at that point.

“We decided our commitment is to the next piece and for us the older music is Webern, Shostakovich and Bartok. I love Haydn but there is a lot of other music out there. Somebody asked me recently if we play Mozart and Haydn and I said, “You wouldn’t ask the Beastie Boys if they sang Stephen Foster.’ ”

That kind of quick riposte gives some clue to the board musical parameters within which Harrington can work.

As a child in Seattle, Washington, he grew up with rock and roll on the radio and admits without apology that when the thinks of quartets, “one of the first that comes to mind is the Beatles. As a force in music they are very important to me“.

“At the same time I’ll never forget the first time I heard Bessie Smith and Louis Armstrong when I was about 16.”

After study at the University of Washington he went to New York and in 1973 founded Kronos.

It was a difficult road and in 1977, with viola player Hank Dutt he went to San Francisco in search of a more sympathetic artistic community. Cellist Joan Jeanrenaud and violinist John Sherba joined the following year.

In the decade since the group’s reputation has grown steadily and their stage presentations of sometimes unusual arrangements for string quartet garnered them a reputation for the unexpected - and sometimes for being too unashamedly market-oriented.

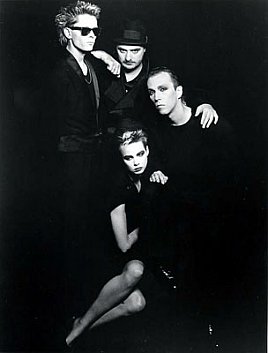

On stage the foursome has favoured striking and loud costumes by avant-garde fashion designer Sandra Woodall, and its publicity shots lean towards to those of an artistic new-wave rock band such as Talking Heads. The music and staging has often been similarly arresting.

“We’ve been doing different theatre-type concerts with stage sets and complicated lighting plots,” Harrington says. “It’s still a concert but there is a different look. We call it live video.”

And the repertoire for the concerts has kept people guessing; medleys of 1950s rock tunes, a piece made up of 26 themes for television shows “from Popeye to Perry Mason and The Flintstones.” transcriptions from jazz composers such as Thelonious Monk, Bill Evans and Ornette Coleman . . . and the Hendrix.

“The Hendrix wasn’t a conscious thing to get to a younger audience,” Harrington says. “I just wanted to have a good time – and he was a hometown composer from Seattle and Purple Haze is one of the great rock tunes of all times.”

But if designer clothes, a sense of humour and a two-metre high robot called Elvik which danced on stage while the group played James Brown soul tunes suggests mere frivolity, the quartet can play things straight – as they do most of the time.

Perhaps it has been too easy to concentrate on the most superficial aspects of the Kronos Quartet’s work, the designer drape jackets and chart successes.

Behind all that they have been assiduously presenting the best contemporary work they can find.

Because the bulk of the group’s programmes are taken up by the more serious works, critics have been obliged to come to them seriously and consider the group’s interpretations of such thorny works as the Bartok string quartets or the four-hour String Quartet No 2 by Milton Feldman.

“You don’t put your instrument down at all during that one,” says Harrington.

By working with jazz musicians such as guitarist Jim Hall and bassists Eddie Gomez and Ron Carter, with whom they recorded albums of the music of Thelonious Monk and Bill Evans, they have also opened up the debate on the nature of improvisation in classical music.

“We wrote an improvised piece last summer,” Harrington says, “but I think there are a lot better composers than us so we don’t do it at often. Terry Riley is one of the great improvisers in classical music today, certainly the best I know of.”

And the group has an understated missionary zeal about the presentation of the serious works in its extensive repertoire.

Within the world of string quartet music Bartok and Schoenberg are rarely surmounted barriers for more conservative listeners. The Kronos Quartet, instead, do a neat sidestep around them by placing those works further down the programme.

The second Wellington concert in the Town Hall opened with Sculthorpe’s String Quartet No 8, book-ended by sections which are almost entirely solo cello. But between times the groups explore all the sonorities of their instruments by plucking, tapping and hitting the strings below the bridge. It is a difficult work but has a curiously appealing quality, perhaps because of its origins in traditional Asian music.

“It’s a great piece to open a concert,” says Harrington, admitting its placement at the start to be quite deliberate. “It opens the ear to a whole range of sounds – like exploring the instrument’s palettes – and some of those sounds recur again in the Bartok and other works.”

Critical comment has been made by some writers who suggest – often in the absence of any other group for comparison – that the Bartok performances do not match those by groups which specialise in performing them.

Harrington admits it may be well be true. It’s a double bind – should they concentrate on Bartok, or open themselves and their audience to the vast possibilities of the newer music? The answer is apparent without him having to say it.

One recent comment in Australia did, however, irritate him. A writer bemoaned the fact that the quartet had abandoned its printed programme – and he had spent all day listening through those works in preparation for the concert.

“We were very surprised to see a programme at all,” he laughs. “Those titles were just suggestions we gave a long time ago. People don’t realise programmes are decided eight or nine months in advance and during that time we’ve probably premiered 20 new pieces. It would be a real pity not to play something great like Astor Piazzolla’s Four, For Tango.”

The lively Piazzolla piece was included as an encore for the second performance in Wellington which kept strictly to the printed programme. It also appeared in the first concert which abandoned the running order of the programme.

“We just saw that wonderful old hall and got a sense of what it was like and then changed the programme to suit. It’s such a lovely hall to play in and you don’t get opportunities like that too often. I don’t imagine too many people were bent out of shape about that though.”

On the Sunday morning before the second Opera House concert the group is holding an open rehearsal for Three Transcriptions, a piece by Wellington composer Jack Body.

Wherever possible Kronos likes to perform music by local composers and Harrington had heard about Body from a fellow composer in New York.

The piece is not easy and in front of an attentive, and noticeably young, audience of 100 or so the group puzzle over the difficult accents and phrasings at the start of the second movement. They play the rapid rush of notes, stop try again and stop once more.

“This is hard, man,” says Harrington shaking his head and smiling at Body who is seated at the front of the stage.

A small compromise here and a change of accent there, one more run through, and it is starting to feel right. After a particularly knotty section has been resolved and played through without pause the audience bursts into spontaneous applause – as much from relief of tension as for recognition of the collaborative effort being made.

“What’s that Beatles song where someone yells at the end ‘I’ve got blisters my fingers’?” Harrington asks to other members of the group. They break up laughing.

The quartet enjoy working with composers – they have collaborated with the most visible contemporary classical composers like Terry Riley, Steve Reich, Philip Glass and La Monte Young regularly, as well as with jazz artists and with rock musicians like David Byrne of Talking Heads for whose film True Stories they performed a short piece.

“A composer knows one way for the music to go,” Harrington says. “They had the original experience and took the trouble to put it into a form for other people to experience.

“But in the end, each of us is a vessel and the information travels through us. A composer is a special person but not necessarily the person who knows the most about it.”

The way the quartet works with composers now is similar to how Harrington himself learned.

“I didn’t study formally all that much. If I needed to learn something what I always did was find the person who knew the most about it and go right to them. It wasn’t till I was 21 that I found a violin teacher I thought could teach me all the technical things.”

Because of the quartet’s policy of playing as much contemporary music as possible Harrington is almost buried under a mountain of tapes, but admits that he enjoys it.

“I review all the tapes or scores and if something is interesting I pass it on to John then it goes on to Hank and Joan. That’s the way it’s been done, listening to the tapes in my thing.”

The search for the new has meant the quartet has built up an enormous repertoire. Harrington is not jesting when he says the Kronos Quartet could stay in a city and play a different programme every night for almost two months and not repeat itself.

In the rare months when the group is back in San Francisco it rehearses at least five hours a day and also fits in recordings and concerts. It is the classical world’s equivalent of rock music life in the fast lane.

The Sunday morning workshop on the Body piece begins at 10.30 and runs for a little over two hours. As the audience leaves the sound crews move in to record the music for radio and within an hour of that being completed the afternoon concert begins.

After the concert, Harrington and the group are seated backstage in the middle of a press of admirers, autograph seekers and those musicians, young and old, thanking them for hauling classical music out of the past and into the present. Then it’s off to Avalon to film a television special.

Harrington returns to his hotel at 11.30 on a cold Wellington night and starts to look for the first substantial meal of the day. We walk the streets and he ponders the next day: an early morning swim, a couple of hours with Jack Body again before catching the 9.30am flight to London via Australia and India.

He will be 31 hours in a plane, straight into eight concerts in England and then through Wales and Ireland before heading home. But his enthusiasm hasn’t waned for what the quartet is doing: performing and premiering new works for a broad-based audience is what he aimed for a decade ago.

“Next year we may cut back a little, maybe do as many concerts but only be on the road six months and not seven. But this allows us to get a lot of new work in front of an audience, a lot of which won’t get there otherwise. We certainly wouldn’t want not to perform.

“Playing is what we do.”

post a comment