Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks: Who Do You Love (1963)

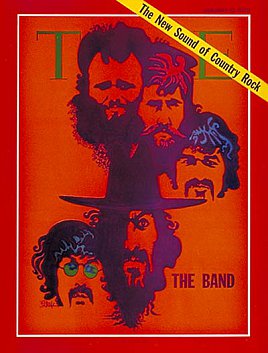

For the record, I turned off the Band around the period they hit the cover of Time magazine in January 1970 - which is to say I never really got into them.

This is no brag that when they went commercial I bailed out, more like that guy who yelled “Judas” at Bob Dylan when he plugged in. Just a case of woeful stupidity.

That the Band are central to any understanding of American music shorn of bombast, but born of rock’n’roll culture, is quite apparent to me now. Back then though I thought they were boring. Three-minute singles by Creedence or stoned Stones sounded much more interesting.

Never quite believed the hype either (if slow head-nodding by friends and their impassioned accounts of particular songs can be called “hype“).

Heard most things but never really listened.

Over time too, it seemed that liking the Band became some kind of credibility template -- and I hated that.

That opinion gets some reinforcement by Chet Flippo in his liner notes to this long-awaited three-disc set.

Chet says simply the Band were too good, couldn’t be reduced to the simplicities and mediocrities of their period (Vanilla Fudge mediocre? Well, I guess so) and so onion-headed critics (and idiots like me I suppose) simply fled in the face of genius.

We onion-heads and idiots feel mighty reassured you’ve spelled that out but invited us in, Chet.

Flippo argues the standard Band line that they changed the landscape of American rock (shifting the perspective away from NYC/LA into some mythical heartland) and they did this with some great songs brilliantly sung by this former journeymen rock outfit who started out playing with Ronnie Hawkins, linked up with Dylan (literally finding a music together) and carried the American vision through a series of albums that people still passionately argue about.

All true.

The Band certainly contain a great story, recounted with particular insight in Levon Helm’s tractor-seat to drum-stool view in his autobiography This Wheels on Fire.

It’s all there: how he literally came from a cotton-pickin’ family in Tornado Alley near Turkey Scratch in Arkansas, grew up listening to King Biscuit Hour, linked up with rockabilly rude’n’rough boy Hawkins, went on the road in Canada and saw the soon-to-be Bandmen join one by one.

They learned their art and survival skills on the road, split from Ronnie and - if my friends, the textbooks and common sense are to be believed - changed rock history and the way Americans saw themselves.

All that American music and myth, and four of them were Canadians?

Of course as everyone from Neil Young to Wim Wenders has proved, outsiders frequently read the Big Country better than those embedded in it.

The Band are clearly one of the great rock stories - for sheer diversity of personality and the alchemy that brought them together they match the Beatles and the Stones. So it demands a strong and sensitive overview.

Across The Great Divide - the title being a Band track but also the name of Barney Hoskyns’ group biography - tries to walk a fine balance.

It goes for the middle ground: two discs of 36 chronological album tracks up until their ‘77 farewell (nothing from the revived Band’s Robertson-less Jericho album of 93 obviously), then a disc of 20 “rarities” and unreleased material which includes the group’s ‘64 Levon and the Hawks single, some previously unreleased live stuff and tracks which collectors and the casual may already have such as five from The Last Waltz (their farewell concert filmed by Martin Scorsese) and a couple from The Basement tapes.

Bandophiles may get their thinking caps on about the paucity of real “rarities” on that final disc.

But most casual listeners should head straight for that disc which opens with Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks’ seminal Who Do You Love? in which Robbie Robertson’s dark serrated blade of a guitar cuts the song in half, connecting intuitively with Muddy Waters’ bitterness and inner fury.

Robbie was 19 at the time.

Do the Honky Tonk and He Don’t Love You which follow - the latter written by Robertson but both sung by the late Richard Manuel who hung himself on the road in ‘86 - is an early single from ‘64 when they were post-Ronnie and recording as Levon and the Hawks. (A previous single as the Squires hasn’t survived)

The former is raw barroom r’n’b driven by a chugging rhythm that Manuel, seemingly intent on ripping his heart and throat out, tears up with the same intensity that drives that guitar again.

Robertson’s He Don’t Love You is rock’n’roll swamp-stomp with a rollicking white soul chorus. It’s a real gem.

Evidence of the Band’s legendary status as a live act is right there in one single, the sheer implosion of talent in one band audibly evident. You can hear why Dylan took them, although he initially only wanted Robertson and Helm.

The disc continues through Basement Tapes songs (Katie’s Been Gone, Bessie Smith, unusual choices I would have thought) and then into some unreleased live tracks (Slippin’ and Slidin’ and Chuck Berry’s Back to Memphis get terrific raucous and rhythm-driven treatments respectively)

A Garth Hudson organ solo takes you into a devout but funky piece and later there’s a live Don’t Ya Tell Henry. Great stuff . . .

And then it's The Last Waltz tracks plus Manuel’s extraordinarily soulful She Knows.

The first two discs necessarily fill in the background for onion-headed critics (and me) who walked away.

And of course the evidence is overwhelming (although those Creedence and Stones singles still work too, right?) There is an uncommon genius at work, a wealth of music to prove it.

But I can’t help think if I’d been a fan and waited that long for a box set of My Band then I’d have wanted a lot more unreleased material than Across The Great Divide offers.

Maybe there isn’t any more?

The books by Helm and Hoskyns tell of dozens of other recordings . . . But then there was that fire when loads of tapes were lost.

Another part of the myth and legend of the Band - and another thing that makes them interesting.

A band that epitomised and contained its own mystery.

Bandophiles will cast a very careful eye over the contents -- and the rest of us (onion-heads and me) will just stand up and applaud.

Or apologise.

post a comment