Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Miles Davis: Right Off (extract only)

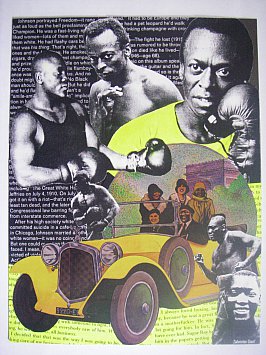

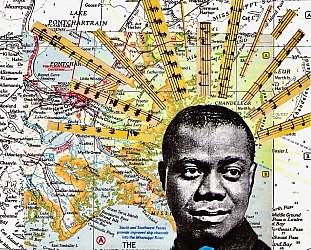

An inch over six feet and usually weighing in just under 200 pounds. Jack Johnson was perfectly proportioned for a heavyweight fighter. But as a kid in Galveston, Texas in the 1880s, he let his older sisters fight for him.

At 12, Johnson jumped a ship for New York, returning a year later to work on the docks where he had his share of beatings. So he took boxing lessons. And got good.

During one ‘battle royal’ (about eight boxers in a ring and left until one man remained standing) he caught the eye of a promoter, fought up the ranks and by 1908 was the first black world heavyweight champion.

The white champ was Canadian Tommy Burns, who refused to meet him.

Johnson sat at ringside whenever Burns fought – in London, Dublin and Paris – and repeatedly issued a challenge.

Eventually, in Sydney on Boxing Day in 1908 – when Burns could dodge him no longer – the fight was scheduled.

Watching it on video it’s a cruel contest. Johnson, six inches taller and 25 pounds heavier, uses his reach advantage to keep Burns at bay, then hitting him with a left and right flurry. Throughout, Johnson taunts Burns – “C’mon hit me Tommy is that the best you can do?” – and smiles at the crowd.

The final minute is lost to us.

Police stopped

the cameras and entered the ring in the 14th round to prevent Burns

from being beaten further.

Johnson enjoyed being champ.

He drank champagne, smoked cigars, drove fancy cars, stepped out with white women and married one.

Over the following decade, any number of Great White Hopes tried to teach Johnson a lesson. Few did, although he became subject to increasing harassment under the Mann Act, the law designed to prevent white women being taken over state lines for immoral purposes.

He was questioned over sex with under-age girls, his wife shot herself, after some of his victories there were lynchings of blacks and race riots.

He was charged with abducting a white woman, sentenced to a year inside, jumped bail and headed for Canada and eventually Paris.

From his mid 30s, Johnson was an itinerant showman fighting exhibition bouts, appearing in movies and on stage and moved to Argentina then Cuba when WW1 broke out. In April 1915, after losing his heavyweight title in the 28th round to the heavier, taller and younger Jess Willard under searing afternoon heat in Havana, Johnson went to London, then Spain where he took part in some bullfights, and Mexico where he opened a bar.

Finally, he returned to the United States and spent 10 months in Leavenworth.

He had a couple more fights (he was 50) and over time the hatred many felt abated and Johnson was recognised as one of the greatest fighters of all time.

He loved fast cars – right up until his Lincoln Zephyr hit a lamppost on June 10, 1946. He was 68.

Johnson’s life, the unwavering self-confidence and his

prowess as a fighter, naturally appealed to Miles Davis who boxed as a

kid and in 1952 asked trainer Bobby McQuillen, to take him on. (McQuillen

refused saying Davis needed to kick his habit. Davis did and began working out).

He became friends with Sugar Ray Robinson, an inspiration for his clear-headed

disciplined approach.

In February 1970, Davis went into the studio ostensibly to

write the music for William Clayton’s doco on Jack Johnson.

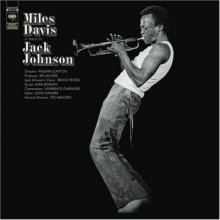

The album, A Tribute to Jack Johnson – two side-long pieces spliced from the sessions by producer Teo Macero, because Davis was using the studio and editing process as another instrument by this time – was released in 1971, barely promoted and all but disappeared.

Only in 2004 with the release of the five-disc set, The Complete Jack Johnson Sessions (Columbia), could the real significance of those three months in the studio be truly understood.

It was Davis’ bridge between jazz and rock, between Bitches Brew and the Sly Stone-influenced funk-rock of Big Fun, Get Up With It and On The Corner released later in the 70s. And the beautifully packaged, well annotated collection of jams and alternate takes revealed an embarrassment of musical ideas from pure rock courtesy of guitarist John McLaughlin (the pivotal player) to groove-oriented soul-funk held down (mostly) by drummer Jack de Johnette.

There is electro-funk jazz with Chick Corea or

Keith Jarrett on electric piano, and Herbie Hancock on organ in places.

Avant-guitarist Sonny Sharrock is there, Dave Holland plays superb electric bass

Bernie Maupin drops by with his bass clarinet and Wayne Shorter plays soprano

sax.

The context is important.

On New Year’s Eve Jimi Hendrix had unveiled his new outfit, Band Of Gypsies (drummer Buddy Miles was scheduled to the Davis sessions but didn’t show because of Jimi commitments); Black Panther radicalism heated up the disenfranchised black communities: Sly Stone (a star of Woodstock the previous year) had his song ‘Stand’ adopted as a Black Power anthem and funk was in the air.

Davis, ever the hipster, put aside his suits, got into urban streetwear and had McLaughlin pull out his wah-wah pedal. These sessions were experiments in sound and according to Maceo “The musicians didn’t know what the hell they were doing.“

But Davis knew, he was in tune with his times. The Tribute album was critically acclaimed and embraced by more rock than jazz listeners who had turned their backs on him by this time.

But listening through this set is like hearing templates for possible directions in jazz and rock.

And despite the presence of white players, this is

– from its funky bottom by Stevie Wonder bassist Michael Henderson to Davis

probing trumpet – black music.

Jack Johnson said, “I’m black, and they never let me forget it. I’m black alright, and I never let them forget it”.

On these sessions, Davis – as he bobs and weaves, parries, ducks low then comes in underneath – is saying the same.

Like this? There is plenty more on Miles Davis at Elsewhere, including an interview, here.

mark robinson - Jan 25, 2011

When I interviewed Chick Corea he told me about Herbie Hancock performing on this session. Herbie had his car running outside the studio, Miles croaked at Herbie "play that keyboard" Herbie protested that his car was double parked, Miles glared at him and Herbie played.

SaveJack de Johnette brings a gig to Melbourne called "Jack Johnson: Soundtrack to a Legend" in March - not sure if it is going to NZ. Can't wait.

Jeremy - Mar 9, 2011

There's a fantastic Ken Burns doco about Jack Johnson called Unforgiveable Blackness - The Rise And Fall Of Jack Johnson. Long but fascinating. And the soundtrack is by Winton Marsalis. Not knowing much about jazz beyond the rivalry between Marsalis and Davis it would be interesting to know which album serves Johnson best.

SaveRickG - May 12, 2012

If Burns was beaten so bad in Sydney, why was he at the race track later that day and Johnson in the hospital for the next two weeks? And if after following Burns around the world for a match for three years, why didn't he give Burns the rematch he was asking for?

Savepost a comment