Graham Reid | | 5 min read

Reggae is one of the bloodlines of New Zealand music. It is there whenever an acoustic guitar comes out on the marae or suburban barbeque, and you can hear it in the hi-tech dub incarnation in clubland and dance music like that from Salmonella Dub, Trinity Roots, Pitch Black and the many bands out of Wellington.

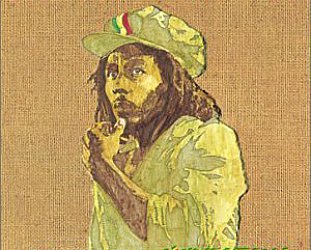

Yet since indigenous reggae burst onto the scene after the arrival of its mentor Bob Marley there has been a decline in the number of bands playing it in a roots style.

Think back to Eighties groups like Dread Beat and Blood and Aotearoa, or the solo work of Ngahiwi Apanui who amalgamated traditional Maori instruments with roots reggae.

And not forgetting the seminal Herbs in the late 70s, or Upper Hutt Posse a decade later who placed reggae alongside rap in their innovative sound.

Reggae has a long lineage, but the music went into decline in the Nineties. Bands broke up and radio moved on to r’n’b and hip-hop -- but roots reggae has always been popular in New Zealand.

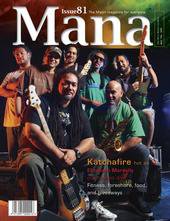

Which accounts for the extraordinary success of Hamilton’s Katchafire who, two years ago, emerged as the hardest working band in the country.

Katchafire took their Marley-framed original music to bars and clubs to the people who wanted it. And thousands did.

Their exceptional debut album, the prophetically named Revival, sold in excess of 30,000 copies (double platinum) and they scored massive hits with songs like Giddy Up, the biggest selling single of 2002-3.

Katchafire had tapped into that bloodline of New Zealand and people, being reacquainted with what they had lost, loved it all over again. It was also a message to the New Zealand music industry that out there was a huge audience which had been marginalised and ignored. These were often people whose lives had been tough but they were still here struggling. For many of them Katchafire epitomised how success is be the sweeter for the struggle.

Katchafire’s music was uplifting and celebratory, and they understood their audience. Their website was filled with praise from people of all ages, many in te reo, who had found the band which was providing the soundtrack to their lives. It was at once original music, but grounded in the spirit of Bob Marley.

“There are a lot of reggae bands out there now, “ said bassist Ara Adams-Tamatea at the time, “but the kind of reggae we play is different, more the Seventies style and very traditional. And that’s why people like it.

“You go to parties and they are still playing the same 70s Bob albums. Why is that? Because Bob’s message is still alive and the things he was singing about are still relevant.”

But Katchafire didn’t just recreate the sound of Marley as some casual listeners thought.

There was something almost indefinably Maori about their sound. It was in the slightly slower beat, the big and musically flexible line-up which hinted at the great Maori show bands, and the concerns for people’s everyday lives.

It was encapsulated in the lyrics of the hit Get Away: “Excuse me sir, me car broke down, my missus left me with the baby now, and I can’t make that date today.”

They brought a unique perspective to their lyrics which, while sometimes adopting the language of Rastafarianism, spoke to the people of this land who were in need of healing music.

Katchafire provided that, and much more. Their gigs were joyous singalong affairs where people of all cultures and affiliations were welcomed. Their audiences are still the most cross-cultural, cross-generational in the country.

Katchafire were, and remain, unique in New Zealand music. They are a viable, touring eight-piece band which can work the length of the country without exhausting the place. They can return to a venue they played just a few months before and pack it out all over again. That is rare for any band, regardless of what style of music it plays.

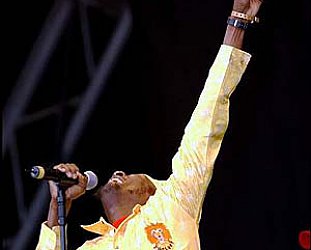

The success of the band was evident in album sales, opening shows for the likes of Michael Franti and Spearhead, gigs all across the country (three in one day on Waitangi Day 2004, in Hamilton, Manukau and Nelson), three tours to Australia and New Caledonia, and in late November headlining at a stadium-filling show in Fiji where they were also filmed for a documentary.

“We didn’t realise how big the fan base was for us there,” says Ara. “When we were walking in the street there were whispers, girls giggling and people giving us the sign. It was great. There was a press conference for radio, television and the newspapers.”

And now they are stepping up again with a cracking new album Slow-Burning which shows them reaching a new level.

From the terrific cover slip -- a cheeky homage to the classic Bob Marley album sleeve from which the band took its name -- to the eleven diverse tracks within Slow-Burning is a leap forward, both musically and lyrically. The title is again appropriate, you will feel the fire from this for a long time to come.

Produced by Chris Macro (of Dubious Brothers) and with international guests, this is a new level of consciousness music from Katchafire which moves effortlessly from classic JA-sounding roots-reggae to material which could be located nowhere else other than in Aotearoa.

While mindful of the traditional they are part of, they also extend their concerns into contemporary issues. When they say “don’t frisk me down because of my brown skin” they also bring dignity to bear, “we must hold our head up high”.

And the deeply felt, fiery I And I stands proudly in the local lineage of politicised reggae that was kick-started by Herbs.

More than on their debut they pull in threads of dub and toasting, There are musical references to the sound of classic Trojan records (Close Your Eyes, Hey Girl Version) but, courtesy of the French horn section Mister Gang whom they met on their first trip to New Caledonia, you can also hear echoes of DD Smash-styled pop.

And on the first single Rude Girl, with toasting by Tuff Enchant, the band open with a tricky rhythm and a nod to the music of Cuba.

“We wanted that out first,” says Ara, “just so people could see we were branching out, and so people knew that could expect something different from us.

“If you don’t grow you become stagnant and we want to continue to grow.”

However Katchafire haven’t sacrificed the pop sensibilities they showed on that debut and classic pop singles like Hey Girl, I Got Ya Back and Close Your Eyes should be all over radio this, and every, summer.

With Slow-Burning, Katchafire have fulfilled the promise of their debut that here was a band schooled in roots reggae, which has honed its professionalism on the road, and has within its ranks songwriters who can take their place alongside the best Aotearoa has had to offer.

Katchafire shows are always celebratory affairs and with Slow-Burning the band have even more to be joyous to be about. Be prepared to celebrate with them.

Written for Katchafire on the release of their Slow Burning album in 2005

post a comment