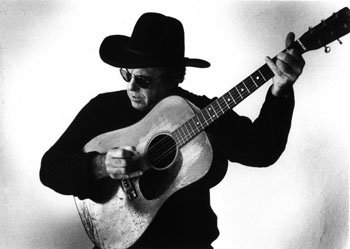

Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Tom Russell: A Dollar's Worth of Gasoline

Julio Gonzalez was pumped up and crazy when he was tossed out of the Happy Land Social Club in the Bronx in mid-March 1990. He was 36, unemployed and had been in the States for only 10 years after arriving with thousands of other Cubans in the Mariel boatlift.

An argument with his former girlfriend who worked in the cloakroom, a couple of bouncers heavying him into the streets, a short walk to the local service station where he brought gasoline...

When the smoke cleared, 87 bodies were pulled out of the predominantly Honduran nightclub. The well-dressed bodies were found piled up on the narrow stairwells. Building inspectors noted the inadequacies of the fire exits.

The politicians got a lot of mileage out of that dollar’s worth of gasoline.

“Oh Happy Land, we are drivin’ towards the Judgment on a dollar’s worth of gasoline …”

Claude Lafayette Dallas jun was a self-made mountain man, cowboy and trapper living in Nevada when he shot down two game wardens come to tell he couldn’t trap game. It took 18 men and 15 months before they caught him in the sage-brush. He was sentenced to 30 years...

When Edith Piaf tried to quit a three-pack habit once, she took to sucking on chocolate cigarettes...

These are the characters who populate the narrative songs of American singer Tom Russell. Delivered with righteous fury and a rock backbeat or spun out as campfire stories, Russell’s songs move across continents and through inner lives of their characters.

Black boxer Jack Johnson counterpunches with white racists by flaunting his relationships with white women; a waitress answers Bill Haley’s “Do you know who I am?” with “To me you look one more tired old man”; and steel workers talk during their last lunch hour on the day the plant closes...

“Yeah, if there’s any benefit to moving around for 20 years as a writer, it’s that you get to listen in bars and keep hearing stories” says Russell in an accent that locates itself somewhere east of California, west of Texas and contains a touch of the rounded Canadian vowel.

“I’m not prompted by the big issues in my writing but by the small things, like how people deal with their problems as opposed to me handing a big answer to somebody on a platter. We often see the truth in smaller things.”

Russell’s reference to his two decades of itinerancy contains the essence of who he is as a writer. He spent the first 18 years of his life in Los Angeles and watched as his father – who had come to California from Iowa – made and lost a fortune, eventually spending time in jail. Russell studied the criminology side of sociology and travelled to Nigeria during the Biafran war with one of his teachers who had been given a study grant to work there.

“I was a teaching assistant but ended up playing more guitar than teaching, I admired songwriters more than academics so I made a life choice – it was a rugged one, but it panned out.”

With his wife at the time he went to Vancouver to stay with a friend he’d met in Nigeria “and put together a country band playing hardcore honky-tonks for 10 years.”

He lit out for Texas to reconnect with the country music he had grown up with on California radio, drifted down to Puerto Rico and finally quit music after a couple of albums. He was driving a cab in New York when Robert Hunter – lyricist with the Grateful Dead – got in the back, struck up a conversation, heard Russell sing a few verses of his Gallo Del Cielo (a song about a Mexican boy who steals a fighting cock) and convinced him to sing at the famous Bottom Line club a few nights later.

It was a second start for Russell who then teamed up with crack guitarist Andrew Hardin – heard on many of Russell’s albums.

Out of that “half a lifetime of guerrilla warfare,” Russell draws on personal experience, half-told stories and bar-room incidents for his tough, tender and always memorable songs.

Music aside – and it is always fine music carved out by Hardin, who has invited comparisons with Ry Cooder and James Burton – Russell tells a good story.

“I grew up with a love of good writing and liked the Beats like Ginsberg and Kerouac and that outsider American literary tradition. I wrote short stories in high school and dreamed of being a novelist as well as a songwriter.

“But I opted for songwriting because it is a more powerful medium.”

His early 90s album Cowboy Real however was a left-turn away from the previous album Hurricane Season with its fierce, post-divorce bitterness in the title track (“baby’s packing the essential things, diet pills, potato chips and gin”), failed dreams in The Evangeline Hotel (“from the 10th-floor fire escape she can see the Great White Way”) and angry, rocking Jack Johnson. Cowboy Real was a collection of cowboy songs some co-written with Ian Tyson.

“I’d thought about it for five or 10 years and it was a hobby project. It isn’t in the mainstream of what I’m doing electrically but after I finished Hurricane Season I sat down in a studio in Brooklyn with my guitar and went back to my roots of country songs.

“Writing with Ian – being on the top rung of that renaissance of cowboy Americana western music – allowed me to accomplish a couple of goals, to do a hobby project for myself and to touch that western audience.

“Initially it was just going to be a cassette for fans, but the label liked it, so they put it out.”

And Russell – whose has toured through Europe and from the Yukon to New Zealand – says together he and Hardin aren’t “a laidback duo by any means.”

“We can bash ‘em out and Andrew plays almost rock ‘n’ roll style, so we can go from being soft to things like Jack Johnson.

“We get a lot of airplay in Canada and Europe, but are still an outsider cult in the United States. The success of John Prine in the States was good because we see ourselves in the same ballpark as him, Joe Ely, Guy Clark, Lucinda and those people.

“We’re just all still out here, knockin’ on the door.”

post a comment