Graham Reid | | 4 min read

I only saw the Doors once, in a packed club on Sunset Strip. That was five years ago.

Jim Morrison had been dead 35 years but there they were -- or at least an excellent replica -- going through their hits as the leather-clad singer exuded menace, animal sexuality and seduction.

The crowd -- mostly people not born when the Doors peaked in the late 60s -- included other Morrison look-alikes.

Quite why the Doors have endured -- and as recently as early 2007 had their studio albums reissued and remixed (with extra tracks) by their original producer and engineer Bruce Botnick -- is one of rock’s more interesting questions.

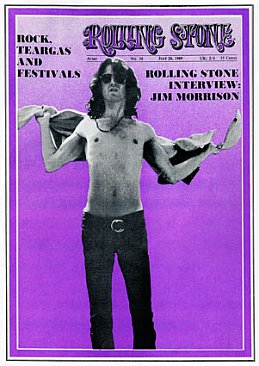

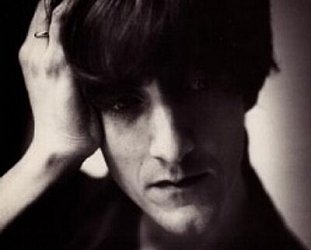

Certainly Morrison’s death at 27 ensured he would never be bald, old and boring like many of his peers. Jim will always be Adonis in leather pouting out of iconic photos, his image untarnished by age.

Ask fans what the Doors’ appeal is and answers invariably come back to Jim: poet, sensual shaman, theatrical performer, sexual rebel . . .

The most curious of those descriptions is “poet“. If he were a poet then his collection The Lords and the New Creatures would have sold better, and the album An American Prayer -- his words set to music posthumously by the other Doors -- would be a best seller.

But his poetry goes largely unread, unquoted, and absent from anthologies, and the album stiffed.

In the end The Doors’ enduring appeal comes back to that often thrilling conjunction of Morrison’s image and words with the music provided by drummer John Densmore, guitarist Robby Krieger and Ray Manzarek on organ, an unusual instrument in rock then and even now.

Listening through to the reissues of the five Doors studio albums released between January 1967 and May 71 -- a journey from the muscular command of Break On Through to a glimpse into the abyss of the dark Riders On The Storm -- it is the music which still impresses.

Jazz-trained Densmore turns a melody on a brilliant rhythmic shift, punctuating even the most mundane of songs (and there were more than a few) with accents and angles; Manzarek’s draws on his classical training and love of blues, and Krieger’s guitar shifts seamlessly from raw blues to mercurial jazz-styled phrasing, it keens and swoons which provide counterpoint or support to Morrison’s baritone, and provides eerie atmospherics on the more brooding material.

But if it were only about the music then the two post-Morrison albums Other Voices (71) and Full Circle (72) would be in record collections. They aren’t.

The Doors were always greater than the sum of their parts, and that was evident on their exceptional first album, one of the great debuts in rock.

Along with Hendrix’s Are You Experienced and The Velvet Underground And Nico albums of that year, the Doors’ self-titled debut charted territory previously unexplored in rock, and provided a blueprint for their career.

Consider the landscape it covers: the challenge and optimism of Break On Through; sexuality and a celebration of life and death; and two exceptional and diverse covers, Weill and Brecht’s Alabama Song (Whisky Bar) and Willie Dixon’s Back Door Man.

The final track is The End, a vision given new life in 79 when Francis Ford Coppola used it in Apocalypse Now -- and consequently enhanced its sinister allure.

Like all such breakthrough albums it proved hard to top: however Strange Days (67) which followed was its equal -- to be fair it followed much the same pattern -- and contained the hit Love Me Two Times (in the era of album stars, the Doors always cracked radio hits and most were written by Krieger), the bad trip paranoia of People Are Strange and the 11 minute nihilism of When The Music‘s Over. These two albums stand up even now, 40 years on.

But by Waiting For The Sun (68) the band was in disarray.

Morrison -- who believed his own publicity -- was by now an uncontrollable drunk, unhappy being the rock star when he aspired to recognition as a poet. Densmore threatened to quit, so did Morrison. The album did however contain the extraordinary Unknown Soldier, and the pop hit Hello I Love You.

The more experimental The Soft Parade (69) took a year to make and is their nadir, not even elevated by the single Touch Me. Morrison, who wrote little for it, distanced himself from the album, preferring to concentrate on his poetry. Its recording was made more difficult by the obscenity charges hanging over Morrison after he allegedly exposed himself at a concert in Florida.

(Densmore later quipped Morrison didn’t, “if he had, he would have tripped”.)

Morrison Hotel (70) was a return to form -- more instinctive and earthy with Kreiger angrily on fire in places -- but it wasn’t until the bluesy LA Woman (71) that they recovered their form fully. Morrison sounded like a mature mix of bluesman and the poet he wanted to be.

Ironically it was to be their last album but contains some exceptional songs: Texas Radio and the Big Beat (Morrison’s most successful and confident spoken word track); the dirty Crawling King Snake, Cars Hiss By My Window, the obligatory radio song Love Her Madly, Hyacinth House and it closed with the still compelling Riders On The Storm.

But it opened with The Changeling (“see me change”) which may have been Morrison’s public farewell to rock life. The once beautiful man-child was now bloated, bearded, smelly and an indiscriminate drunk.

Shortly after the album was finished Morrison the rock-poet changeling went to Paris. He drank and died, but got what he wanted: his death certificate reads “poet”.

Jim Morrison wasn’t much of a poet and writer Dylan Jones was probably right when he said, “Jim got out before he was found out”.

But for four years he was a rock god, albeit flawed, and -- with the good fortune to have the support of exceptional musicians -- he realised it in places all over these albums, three of which are essential.

post a comment