Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Big Star: Thirteen

The reputation and influence of some artists far outstrips their sales figures.

Dylan – even at his various peaks – was hardly shipping out albums by the crate load and Van Morrison’s seminal/essential/classic (pick your own adjective) Astral Weeks clocked up sales of only a quarter of a million copies in the States.

The trickle-down of the Sex Pistols and Velvet Underground is everywhere, but add sales figures for the Bollocks and “Warhol banana cover” albums and you aren’t even close to either of Springsteen’s ‘failures’ like Human Touch and Lucky Town.

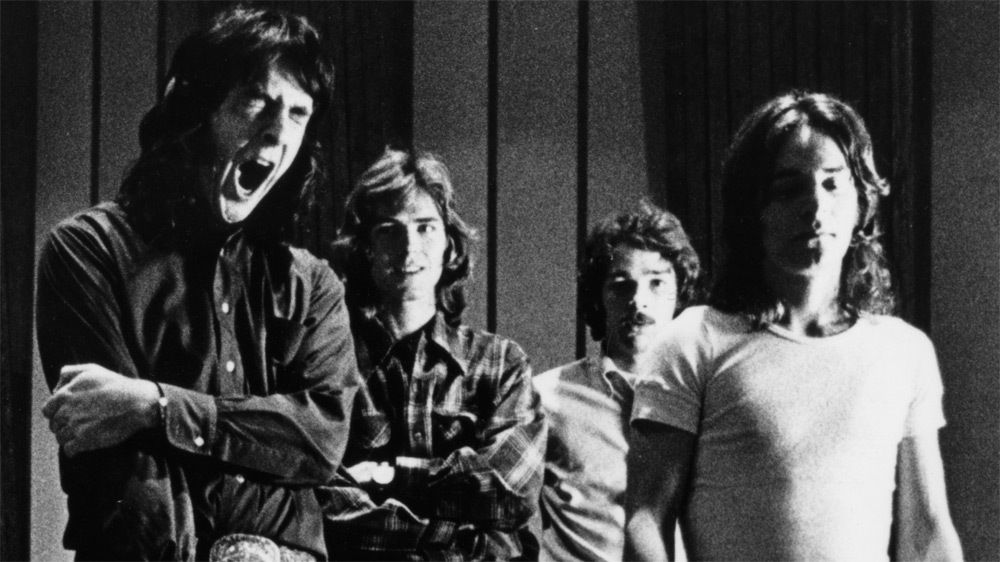

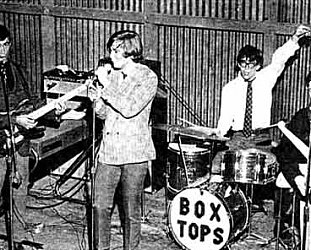

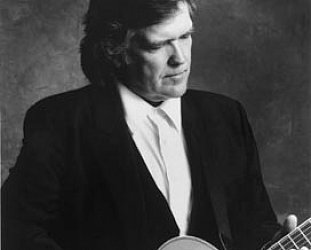

Round up the usual suspects (REM, Martin Phillipps of the Chills, the Replacements, Teenage Fanclub) and one groups gets a regular namecheck: Big Star, the Memphis band of the early mid-70s led by cult figure Alex Chilton, who’d come to prominence in the 60s as the teenage singer of the Box Tops (The Letter, Cry Like A Baby, I Met Her in Church).

Hipper folks than you and me would have you believe they were “always into Big Star.” If they were they had a funny way of showing it. The records sold nothing.

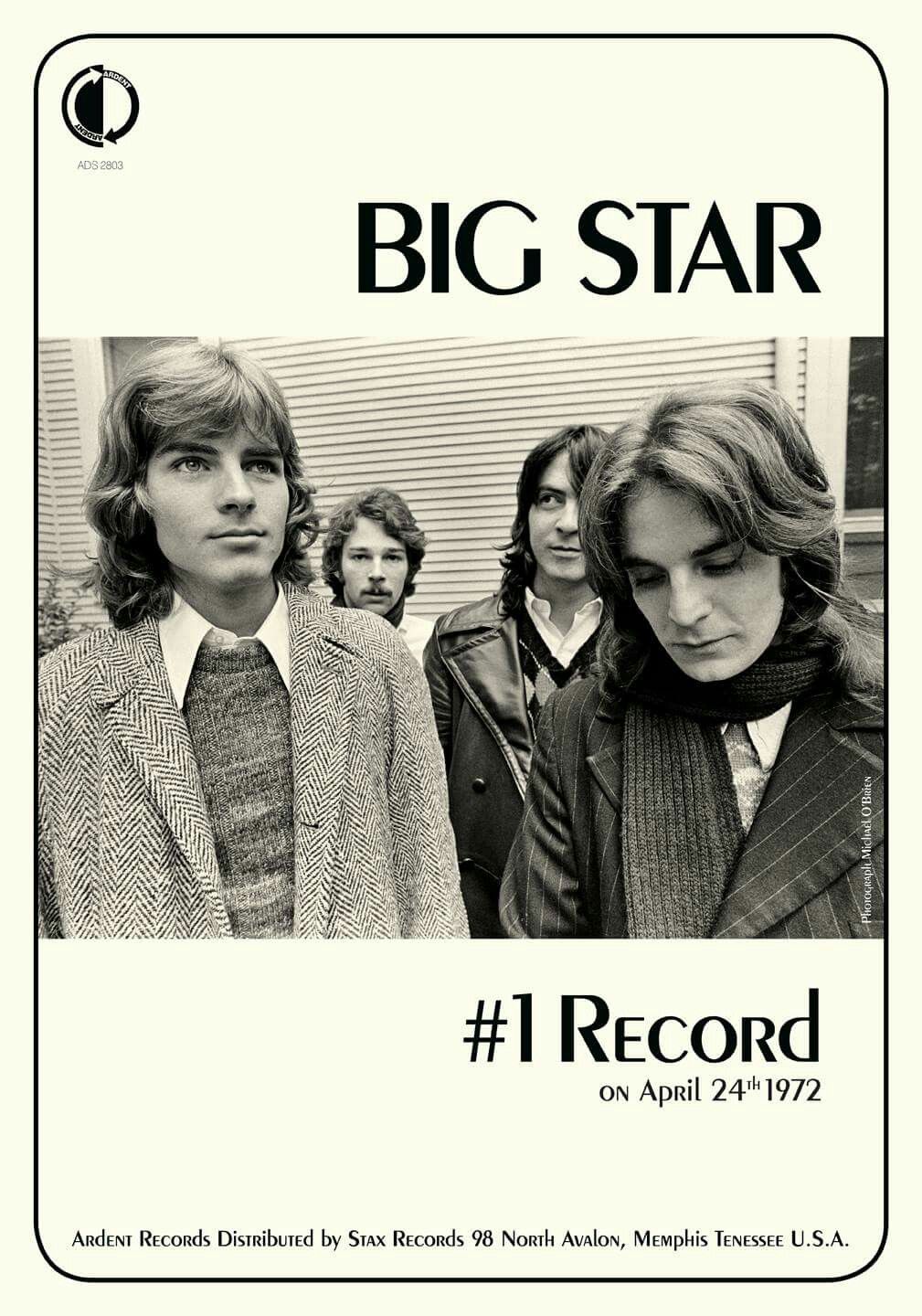

Anyway, Big Star’s albums weren’t even been available for years (except on microscopically small labels). Until the early 90s.

Then the band’s first two albums were repackaged on single CD by Stax, and Ryko -- the label that releases spectacular oddities like a six-CD set of Yoko Ono -- put out Third/Sister Lovers (released three years after the band broke up in ’75 and barely seen since) and Live, recorded after those first two releases.

Then the band’s first two albums were repackaged on single CD by Stax, and Ryko -- the label that releases spectacular oddities like a six-CD set of Yoko Ono -- put out Third/Sister Lovers (released three years after the band broke up in ’75 and barely seen since) and Live, recorded after those first two releases.

There was also a solo album by Chris Bell, a founder member of the band who quit after the first album and died two days after Christmas 1978 when his white Triumph TR-6 went head-to-head with a telephone pole.

The three Rykodisc albums are neatly packaged with extensive liner notes, the Bell story told by his brother in an honest account of a life in music which began when Bell, like Chilton, fell in love with Beatles pop and had the not wholly original idea of starting his own band.

Big Star were unfashionably poppy for their time, which partly explains why the Bangles covered their obscure pop masterpiece September Gurls in 1990 and the Replacements sang “children by the millions scream for Alex Chilton.” They didn’t of course – but may have, given the chance, because, as writer Holly George Warren wrote in her interview piece with Chilton in Option magazine at the time; “Chilton and Bell became the Lennon and McCartney of Memphis.”

And it’s the Memphis reference which is important.

As liner writer local Rick Clark puts it on Third/Sister Lovers: “We were full of ourselves.” The Elvis legacy, Stax/Volt, local chart hits ... It was a golden age for Memphis that ground to a halt as times changed and greed picked at the bones of what remained.”

Chilton lived through it all... and weirdly at times.

Sometimes his stark lyrics, pop formalism and fuse-wire guitar playing put them closer to some forerunner of Television. But with soul.

Chilton would also write the uplifting pop soul and cynical Thank You People and the Byrdsian/REM hybrid Jesus Christ. On Third they play a reverential and fragile Femme Fatale. They attack Ray Davies’ Till The End of the Day and Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going’ On in the extra tracks the CD format offers.

Chilton would also write the uplifting pop soul and cynical Thank You People and the Byrdsian/REM hybrid Jesus Christ. On Third they play a reverential and fragile Femme Fatale. They attack Ray Davies’ Till The End of the Day and Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going’ On in the extra tracks the CD format offers.

Try putting all that together plus a lot of Roger McGuinn and you almost get a bead on where Big Star was coming from.

By the time of these albums Chilton’s world weariness had taken on a dependency problem. Producer Jim Dickinson had been brought in because he “was very adept at venting lunacy in a perversely Southern fashion.”

A Rolling Stone reviewer of the reissues called Third/Sister Lovers “guitarist-singer Chilton’s untidy master .... beautiful and disturbing, pristine and unkempt.” That’s fair.

Live is a rare find, taken from a tape of a ’78 radio broadcast which some of the dB’s/REM cohorts had kept all these years.

It’s energetic and comatose by turns. It also includes the radio interview in which Chilton refers to the touring life with the Box Tops as “pretty scummy” and says “we’ve heard that before” when told of the critical acclaim for the then-released second album. Can’t find the albums in stores though, he notes dryly.

He follows those comments with a spare acoustic set which includes an elegant piece of sexual anxiety and the rock redemption written when he was 13. He then offers Loudon Wainwright’s ongoing suicide note of musicians, Motel Blues.

Chilton and Big Star are never dull.

Shadowy, tired and depressed? Yes.

Rocking, poppy and elevating? Yes.

But dull? Never.

Chris Bell’s solo release I Am the Cosmos, on Rkyodisc, is a collection of similarly thoughtful, melancholy pop painted in slightly darker tones and with more glum lyrics. His brother writes an eloquently straightforward account of Bell’s short, passionate twilight life in the liner notes but, despite brittle songs of pop precision, there are a couple of places where you are driven to shout “go ahead and jump.” The pop simplicity of You and Your Sister in three different versions redeems all, though.

Big Star were a great band in that dissenting American pop tradition whose pockets were felt up more than once by a legion of musical disciples such as Cheap Trick, the Shoes and so on.

The Great Lost American Pop Band, as someone said recently. Too true.

But that’s only my opinion and I can hardly be objective. Like everybody, “I was always into Big Star.”

I've got the reissues to prove it.

post a comment