Graham Reid | | 10 min read

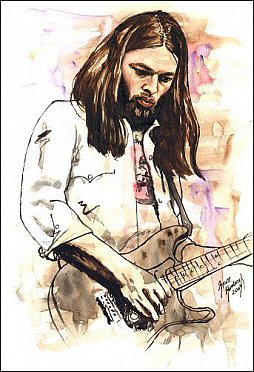

Rock stars shouldn’t talk this way, not in these well-rounded vowels and carefully constructed, oh-so English sentences. But then, this is David Gilmour from Pink Floyd – and as rock bands go Pink Floyd are no ordinary band at all.

Here is the band which presents astonishingly visual concerts, every couple of years unleashes a monster of an album and then disappears into silence for long periods.

But on this day just before Christmas 1988, David Gilmour, lead guitarist and mastermind behind the new Floyd album A Momentary Lapse of Reason, is keen to talk.

He’s just come back from carol singing at the home of Phil Manzanera, the guitarist from Roxy Music who co-wrote One Slip on the album, and very comfortable with the idea of an interview before the band’s Auckland concert at Western Springs on January 22.

Then again, there actually is a bit to talk about on the Pink Floyd front these days and it all comes down to exactly what, or who, Pink Floyd is.

A little history here first, then we get to the bit about lawyers and dirt-slinging and litigation over the use of the name Pink Floyd.

Sounds strange? It’s a strange world.

Can you image carol singing at Phil Manzanera’s house?

Way back in the early ‘60s art student Syd Barrett founded Pink Floyd with Rogers Waters, Nick Mason and Rick Wright, architecture students in London.

After the usual shuffling of line-ups to include a few other friends, the group settled down as The Pink Floyd, a name picked up by Barrett from an old blues album he had by Pink Anderson and Floyd Council.

At the time the bulk of Pink Floyd’s material came from Barrett who, as lead guitarist and vocalist, shaped the sound around his own idiosyncratic ideas.

The first single, Arnold Layne, was about a chap who pinched ladies underwear off clothes lines.

But Barrett was more seriously troubled than his unusual songs hinted at.

His mentality instability, combined with pharmaceutical ingestion, put him over the edge and David Gilmour was brought into the band.

With Gilmore on guitar, Waters handling the bass and the bulk of the song writing, Nick Mason (drums) and Rick Wright (keyboards) the band went on to become the mega-monsters of the ‘70s who gave us The Dark Side of the Moon, Animals, The Wall and a few years ago The Final Cut.

The title of that last album is full of ironies for it saw the end of Pink Floyd As We Know It.

Simmering disputes within the band had surfaced during the recording of The Wall and after The Final Cut main-man Waters called the whole thing off.

Waters walked and the hard words between him and the rest of the band have been carried by the media in a very public slanging match.

And in came the people with briefcases.

The short of it is that Waters doesn’t think the other guys should be using the name Pink Floyd. After all, he argues, he wrote all that stuff.

That’s where the rounded vowels and quiet reasonable approach of David Gilmour comes in.

“The state of play is that Roger has brought two or three actions against us which will probably go to court in about late ’88 or early ’89, maybe even later.

“That’s if we don’t settle it first.

“But that’s really all he’s done. He hasn’t done anything which stops us from working, so we don’t have any problems in that sense. We’re trying to ignore it and just get on with things, actually.”

Simply getting on with things hasn’t been all that easy as the war of words between the two sides of Floyd reached a scream some months ago.

Waters is on record as calling Gilmore, Mason and Wright (who he dumped from the band during The Wall sessions) “a spent force creatively” and stating flatly, “If one of us was going to be called Pink Floyd, it’s me.”

But Waters is in real trouble.

Despite being the main force behind The Wall, The Final Cut, Dark Side of the Moon – in fact everything that people associate with Pink Floyd – his new album, Radio KAOS, barely crawled into the Billboard Top 100, whereas the new Waters-less Floyd album rocketed into the Top 10.

While Pink Floyd filled big venues in the Stages in the months prior to Christmas and fully expect to do the same through New Zealand, Australia and Japan, Waters’ audiences were much smaller.

The Waters argument is that it all comes down to the name. Use it and you are onto a winner.

Gilmour agrees.

A check the credits on A Momentary Lapse of Reason shows the bulk of the ideas and input came from him, but he didn’t opt to use this material for a solo album as he has in the past.

“I never considered doing another solo album, after all I’ve spent 20 years of my life building up Pink Floyd into the thing it is and I figure I might as well use it.

“I couldn’t possibly put on the sort of show we are doing if I was a solo artist. I’d lose money.

“To put it in the most real and simple terms, my solo name isn’t worth what Pink Floyd’s is worth.

“It would take several years and a very, very hard slog to build it up...and when I’ve done it already with Pink Floyd I can’t see any reason, not have any desire to do it again.”

Perhaps the wisdom of that insight comes from the luxury of watching Waters’ solo career languish.

“Well, one has to make one’s own decisions in life and stick with them,” Gilmour says slowly.

“Roger hasn’t helped his own cause by trying to time his records and tours to coincide with ours.

“He thinks it’s going to do us some damage, whereas all it’s doing is damaging him. If he spent half as much time and energy making his records and getting his tours right he could have had a better career than he currently has.”

Yet for all the animosities and serious legal jargon which surround the Waters v Floyd case, it comes as something of a surprise to hear Gilmour say he had spoken to Waters as recently as that afternoon.

“Today’s discussion was...fairly amicable,” he says pausing just long enough on the final words to drip them with a little meaning.

“And tomorrow I’m going to see him to see if we can settle some of our differences.”

If the nub of the impending case is over use of the highly bankable Pink Floyd name, Gilmour isn’t worried about the possibility of losing it in front of a judge.

“I haven’t even considered that possibility because it won’t happen. We will be able to carry on as Pink Floyd.

“Roger left the group,” he says emphatically, “and he didn’t invent the name or start the group all by himself. There’s two other original members in there and I’ve been in nearly 20 years so we all have the same rights.

“After all, he left on his own accord and quite voluntarily, so can you seriously see any judge in the world saying, ‘you’ve worked at it for 20 years but you’re not allowed to use the name?’ ”

And, says Gilmour, “maybe all the fuss that Roger’s making is good publicity for us too.”

Not that Gilmore-Mason-Wright line-up has needed the publicity.

If the name didn’t guarantee it as of right, then a Momentary Lapse of Reason has all but sunk Waters as any kind of Pink pretender – despite his former role.

While Waters has called A Momentary Lapse of Reason “a very facile but quite clever forgery” of the Pink Floyd sound and made disparaging comments about Gilmore’s lyrics, Gilmore is both proud and a little defensive of the album.

“I have a studio at home and tend to work away on stuff by myself but I wouldn’t start an album until I had enough material of good quality. Some of the material I discovered later on I didn’t like enough or I couldn’t quite write the right lyric to.

“So we lost some in the studio, but we certainly had enough material at our disposal when we started to be fairly certain we could make a good record.

“I also think I’m quite a good lyric writer and some on the album are very good. They certainly stand up to a lot of other people’s lyrics. The average quality of lyrics in the music business is not very high and so it’s not hard to be beat.

“They may not be as intense or as clever as Roger’s but its one aspect of our career and business I’m not extremely experienced in. I’m a new boy to writing lyrics and I don’t know how far I can go with it.

“But I’m happy with those on the album. They’re fine.”

Unlike the last few Waters-penned albums, the new one has no consistent theme running through it which has been a hallmark of Pink Floyd albums.

“I don’t care for consumer expectation a lot,” Gilmour says. “My aim is to please myself, or more correctly our aim is to please ourselves, and we figure if we do something we’re proud of then it’s great.

“We thought for a while we might try a concept album and had one or two things we were thinking about. But I thought we were limiting ourselves and trying too hard to get titles to fit.

“Eventually we thought if a theme is going to come along later, it will come along, if not...

“But I didn’t sit around thinking, ‘how do we make this more Pink Floyd? Is this what Pink Floyd would do?’“ he says, smarting a little from Water’s contention that the album had been made with the intention of making “something that sounds like everyone’s conception of a Pink Floyd record.”

From all that he says, Gilmour is clearly the man at the helm of the current line-up of Pink Floyd. He wrote the music and lyrics (with a little help, but none of it from Mason or Wright although in-studio contributions are hard to measure), his name is at the top of the lengthy cast list and he produced it with long-time Floyd offsider Bob Ezrin. The liner photo shows on Gilmour and Mason, keyboard player Wright now reduced to being a salaried member whose name gets the smaller type.

There is the temptation to speculate on whether the band is now any more democratic than it was when Waters charted its course.

“As I’m the one who is actually doing most of the writing and most of the stuff in the studio, it’s not even likely the others will disagree with me very much unless they’ve got a strong feeling about something not being right. Then we sort it out.

“It’s not democratic in as much as I’m likely to get my way if I want to get my way. But it is democratic in that I’m likely to do what at the band thinks we should do if I think there’s a good reason for it.”

Not surprisingly, the new album takes up a large part of the current Pink Floyd show, the one which swung through the States from September through December and begins its Australasian/Japanese leg at Western Springs in a week.

“It’s quite a long show, nearly three hours and the album takes up about 50 to 60 minutes and there’s an hour and a half of old stuff.

“The earliest thing we do is One of These days from the Meddle album. We don’t happen to have found anything older than that which we all like enough to want to play.

With the new album not having a concept, the show is also freed from an artificial linear structure, says Gilmour. But the band’s legendary ability to pull off something spectacular is undiminished.

“You don’t get the Spitfire,” he says referring to the aircraft which formed a centre-piece of the old Dark Side of the Moon shows. “But you get the whole shebang.”

The Floyd show includes their trademark lasers and computerised light system, a rear-protection screen, videos, beds and fireworks, smoke effects and flying pigs.

And somewhere in that are the musicians.

“We are about 11 people on-stage including three backup singers. A couple of them, Scott Page the sax player and John Carin who co-wrote Learning to Fly, were on the album. But I don’t know what the size of the whole sound and lighting crew is. About 70, I suppose.”

Gilmour, now in his mid-40s, is still enthusiastic about the band he has committed half his life to.

“We all try to do something to keep fit once in a while, a half-hearted attempt at squash or racquetball and regular exercise of the right arm,” he laughs

“I’m going to take quite a long holiday after this though.

“I’ve got quite a lot of material written, enough for another album.

“But no plans really, I’ll keep doing what I’m doing until it gets boring.”

post a comment