Graham Reid | | 10 min read

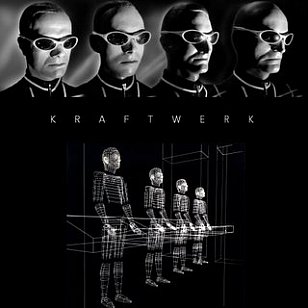

Kraftwerk: Pocket Calculator (from Computer World, 1981)

Ralf Hutter -- founder of the innovative German electro rock pioneers Kraftwerk rarely does interviews. And when he does speak to the press he sometimes doesn’t make it easy. One reporter tells of the constraints being placed on questions: the first being no asking about Kraftwerk.

Kraftwerk are, shall we say, different: their Kling Klang studio in Dusseldorf has no phone, no reception area and all mail delivered to it is apparently returned unopened; when they first came to attention in the early 70s they rarely played live and their perfectionism in the studio meant there were long delays between albums.

They

cloaked their music, albums and lives in an almost Teutonic concern for

efficiency, automatism and industrialism. They loved machines and technology,

wrote about autobahns and train travel, behaved as Futurists already living in

the future, and were astonishingly influential.

Albums

such as Autobahn (1974) profoundly affected David Bowie and Brian Eno,

DJs like Derrick May and Afrika Bambaataa, and producer Giorgio Moroder (who

lifted the repetitive Kraftwerk rhythms for Donna Summer disco-hits like I

Feel Love). They are probably responsible for the whole electro-rock

movement of the 80s.

Given

the mystery, the music and the effect they had on popular music it is

frustrating that Hutter does so few interviews.

And

on the rare occasions Hutter does speak it appears his answers are elliptical,

questions deflected and nothing of a personal nature is revealed. Other than

that they are all mad keen cyclists.

Hutter’s

co-founder Florian Schneider, after whom Bowie and Eno named the track V2

Schneider on the Heroes album, is entirely off-limits these days: he

no longer tours with the band.

Despite

this lack of information about them, Kraftwerk have a slavishly loyal following

and their appearance at the 2003 Big Day Out was little short of astonishing:

four men behind laptops, motionless, making repetitive, minimalist electronic

music while computer-generated images flicked up behind them.

In

an age when rock musician prowl the stage, work the audience and ask us if we

are feeling awwright, Kraftwerk were the antithesis: intellectually remote,

anonymous, aloof -- but producing thrilling music to a capacity crowd which

bayed its approval.

It

was an extraordinary performance, if you can use that word about four men who

might as well have been automatons.

Oh,

and they tour with robots who sometimes perform instead of the band.

All

this makes Hutter’s reluctance to be interviewed incredibly frustrating.

Yet

quite unexpectedly here he is on the line from Dusseldorf sounding chatty,

laughing even, and directly replying to every question put -- including those

about Kraftwerk, the studio, things of a personal nature and, of course,

cycling.

So

why would this normally reluctant man want to speak now, on the eve of a

concert in Auckland which, if that 2003 showing is anything to go by, is almost

guaranteed to sell out quickly.

“When

there is something to say, why not say it?“ he says, which is either Zen

simplicity or Teutonic directness.

Thank

you for taking the time because I appreciate you are busy. You are playing in

Krakow in a couple of days?

Yes,

we are travelling there tomorrow and we are doing three dates and finishing a

festival, we are some kind of ‘highlight‘. I think it will be a beautiful

occasion in an old industrial complex re-functioned for cultural events. So we

travel tomorrow to set up.

Does

it take Kraftwerk longer to set up than most bands given the amount of

technology you have?

No,

faster I think. Two or three hours. But it is more like checking cables and

connections and having the computers working properly. It’s not so much a

physical set-up.

Is

it easier now to perform live than it was say 20 years ago because the

technology is better?

Definitely,

we’ve been very lucky that the technology developed in our direction. (laughs)

This is what we envisaged in the late 70s when we worked with mostly analogue

[equipment] of course. Then we composed the concept of [the album] Computer

World coming out in 81 and we didn’t even have computers at that time. So

that was more like a visionary album. We only got that technology, a small PC,

around the tour of that album and we used one on stage just writing letters.

Just typing them in, not even in synch or anything. Just live, and a guy

putting that on screen.

So

we have been very lucky because you can imagine in the late 70s the travelling

problems. We couldn’t tour at all because all our drum tracks were recorded and

were synchronised by sequencers.

Did

you want to tour more? The image of Kraftwerk was that you were very reclusive,

you didn’t do interviews and you didn’t perform live every often. Would you

have preferred to have performed more back then?

Yes,

because in the late 60s and the early 70s Kraftwerk was the man operating the

machine and was not a museum. It was a live electronic outfit and we came from

free form improvised music, classical or certain jazz. And so at one point we

were stuck with all this complex analogue technology that took so long to set

up we couldn’t perform the music to the same level as on record.

We

had multi-tracked on record so on stage we used tapes, especially for the drum

tracks. So the drummers were just posing. (laughs) Then with computer

programmes in the 90s it was like a restart in 91when we finally had the

technology. It had developed to our standard and we could afford it, and could

travel with it. It is light and very compact.

I

saw you in New Zealand when you played The Big Day Out and people were very

impressed. You mentioned writing letters earlier on. People thought that you

could have been sending e-mails home to your friends because that is what it

looked like.

Yes,

that is a very funny vision. Of course there is black humour involved so

whatever people have -- serious thoughts or whatever -- are okay. Electronics

is very mind-stimulating music. It is not instruments like a violin where you

admire someone playing a violin and their technique. This is more essential. It

is basic frequencies and we have a wide range of audible frequencies from 20 to

20,000 hertz.

There

are no limits, the limit is our creativity and we have the instruments . . . .

but this time for the first time for you we will have the robots.

Last

time they had to stay in Dusseldorf and they were very fat. But this time they

will travel with us.

Speaking

of technology, I enjoy Kraftwerk and get a sense of fun out of the music, but

also there is an ambivalent feeling because it is technology which tends to be

alienating and emotionally distancing?

I

think there is that, but it has to do with the people operating it. If you just

make bank accounts or text or make financial calculations, just technical

configurations, that is only one type. But creativity, computer art is

different and that is what we are doing, creating computer patterns of sound

and images, a technological multi-media performance that we create ourselves.

We create the visuals that are synchronised with the music and sometimes we are

working with outside artists or cameramen. Basically we develop the whole

Kraftwerk concept.

And

you trigger your images live, or are they predetermined?

Everything

is on-line and in real time.

So

when you are on stage and you improvise, because I know you do a measure of

that, you are also triggering the appropriate visual imagery.

Yes,

but not everything can be done yet. When we rehearse in the afternoon or when

we change from country to country we change the languages. When we go to Poland

we will do Pocket Calculator in German because they want to hear the

original language, but in New Zealand obviously we will sing in English --

although I may use some German words, and we will create the images out of our

storage.

So

in a way some people call it live DJing. With the Kraftwerk repertoire we now

have maybe 40 years of sounds in our computer memory, so we are able to use old

and new sounds to modify and modulate our music. Some people call it sound

design, from 40 years of the Kling Klang archive.

We

have the original Autobahn sounds from 74 and then we modify and work

with those, and we might change them during the performance. Although there is

a basic structure so everybody knows where they are going.

If

you didn’t you’d be a free jazz group at that point.

Yes!

Although we do have some free jazz type of feelings: no harmonics, atonal

things and frequent improvisation.

One

of the things that was always said about

Kraftwerk and explained why there was such a delay between albums was because

you were perfectionists. You’ve said you can replicate exactly on stage what

you do in the studio. That is important to you? Because when a rock band is on

stage or at a classical performance people don’t expect, or perhaps even want,

to hear the same as the studio.

No,

we treat the records as a documents in time and for example something from 1977

is there, but now it is 2008 and it will sound completely different -- but it

is still the same composition. Our compositions are very minimal --

minimum/maximum -- but we have all the maximum possibilities of changing and reprogramming. Even during the tour we

would do that. There are experiments all the time.

Who

is coming as Kraftwerk to New Zealand, because I see Florian hadn’t played with

Kraftwerk in Ireland recently.

Yes,

he never likes touring so in the last years he is working on other projects,

technical things. So we are travelling with our live set-up as on the last

American tour and now Europe. We are me, Mr Henning Schmitz, Mr Fritz Hilpert

and Mr Stefan Pfaffe who is programming visuals with us.

Another

interesting area where Kraftwerk seems separate from what we might call rock’n’roll

culture is that people in rock are very attached to a band having the same

line-up. Whereas for the music that you make it may not be necessary the

membership stays the same. The Ramones changed members because in a sense it

didn’t matter who was up there, the sound was important.

Yes,

it is a strong concept. Kraftwerk is a concept for electronic music and when I

started with Florian in 1970, even before that when we were students actually,

we always worked a lot with different musicians and many other people like

artists, painters and poets, and we have technicians or computer programmers,

cameramen and animators, and people who do the album covers. We work with

people in the printing stage. And graphic people.

So

we are involved in all different levels which makes it for me very interesting.

When I was a kid I never liked being at the piano, I hated that. So we keep

alive by working these different fields.

You

studied architecture didn’t you?

At

one point I did, and constructing music and live performance comes from the

same spirit.

It

makes sense that you would want to be involved in album covers in that you have

an eye for design.

Yes.

Because sometimes, as you know, some people just make the music and somebody

else is developing the video concept for them. That’s not the case with

Kraftwerk, we do everything ourselves. And that is how we worked right from the

beginning.

One

of things about Kraftwerk is that you have remained largely anonymous in that

you don’t do too many interviews and people don’t go to your studio. Which

makes me wonder -- but thank you very much anyway -- why are you talking to me

right now? You probably don’t need to do this.

We

do once in a while when there are things to be said or when there are things to

make clearer. When there is something to say, then why not say it? But in general show business people are being

used for their image. For us part of our work is exchanging creative ideas and

travelling into different cultural contexts. Like we go from Poland into

Ukraine now for the first time, and after New Zealand we perform in Singapore.

We’ve never been in that part of the world and so we are also curious to

communicate with our music into different cultural contexts.

It

is the minimum/maximum concept.

I

think people in popular culture talk too much about themselves and the more

they do that, the less important the work becomes. For many people the

interview is the most creative thing they do.

Exactly,

for us it doesn’t make sense because we have visual media.

I’m

curious about 8-Bit Operators [the 2007 album on Kraftwerk’s label where

musicians interpreted Kraftwerk music using very primitive pocket calculators

and Game Boy equipment]. The challenge those people had was to make Kraftwerk

minimalism even more reduced.

Yes.

It is mind stimulating, the minimum/maximum coming from sound levels and

thoughts and ideas. Like Autobahn and Trans-Europe Express are

very basic and elementary ideas, but they offer a pattern or concept for

improvisation. And we use very few words, sometimes even just phonetics so they

become the music itself like ‘dah-dah’ or ‘tchuk-tchuk’ vocals. Like in the

beginning though as we said, it is very difficult to talk about this music

because everything is said in the music, and that is what we are still trying

to work out.

This

may be why when people talk to rock musicians they rarely talk about the music

but about their lifestyle, but you don’t do that either.

Yes,

we call ourselves musical workers, kraft-werk. We go to the Kling Klang Studio

and we speak with music. That takes longer, it is not just every year a new

album because we still really haven’t found an instrumental form and then just

do a new selection songs. In our case it is different because the studio, the

technology, is an influence which means it unfortunately takes longer.

I

remember speaking to Philip Glass when he was very much a minimalist and he

observed that if you set up a repeated pattern of 20 notes you only needed to

change one and it would sound like thunderbolt.

Yes,

because it makes for a different composition. Or you change the tempo.

Are

you disciplined, do you go to the office, the studio, every day?

Yes,

to Kling Klang, that is our office where we work on our laptop computers or

keyboards and I do my speech-singing and Vocoder.

And

when you are not touring you go in regularly?

Well,

we ride our bicycles. Unfortunately we couldn’t bring those to New Zealand but

I know you have hills and mountains. That is where the composition comes from,

our cycling activities. It is our electro-lifestyle. (laughs)

As

someone who doesn’t cycle I have to ask: what is the attraction? Because I just

don’t get it.

It

started 30 years ago -- although obviously in our childhood too -- it was

man-machine and it in a way is the men of Kraftwerk on their machines, like

cycling.

On

the other hand it is similar to music because it is always going forward and

you keep a rhythm and you keep your breath -- and try not to fall off.

Once

you stop, you fall off.

Gerald Mcneil - Nov 7, 2008

In my teasure box of keepsake's I possess.Autobahn,Electric Cafe,Computer World,Radio-Activity,Tour De France,(Soundtracts)Trans Europe Express,and lastly Aerodynamik(the cd single)...Signed by Ralf Hutter...Permafrost!...Don't you think?...Gerald McNeil.Glasgow.Scotland...Thank you.

Savepost a comment