Graham Reid | | 3 min read

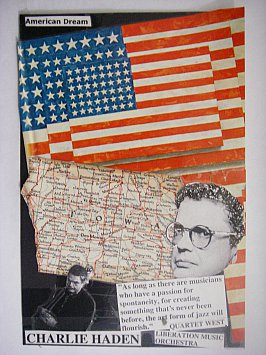

By rights, 71year old bassist/composer Charlie Haden shouldn’t be around in jazz today. Like so many of his generation he had a heroin addiction in the early 60s and often wouldn’t show up on the bandstand until midnight, and even then only be half there. But there’s also another reason.

Haden was born in Shenandoah, Idaho – hardly a hotbed of jazz innovation – and in his early years played with the family country and western band. His roots are in the great American traditions of folk and country and that makes him one of the most durable and interesting players in jazz today. He draws on a deep well of inspiration and isn’t unfamiliar with the classical repertoire flyer.

Haden moved to Los Angeles after high school and fell in with Art Pepper, Dexter Gordon and others -- then met Ornette Coleman in 1957, a chance encounter when he dropped in to a club when Coleman sat in with the band playing his distinctive white plastic alto.

“He played three or four phrases,” Haden would recall, “and it was so brilliant I had never heard any sound like that before. Immediately the musicians told him to stop playing and he packed up his horn, but before I could reach him he’d already left through the back entrance.”

Haden tracked down Coleman which began a lifelong association starting with the revolutionary albums with the prophetic titles: Something Else!, Tomorrow is the Question and The Shape of Jazz to Come. Haden was there for Coleman’s Free Jazz album of 1960 and continued to play with Coleman, or his alumni of Dewey Redman, Don Cherry and Ed Blackwell in Old and New Dreams.

Over the years this lifelong socialist extended himself with his own Liberation Music Orchestra for whom he wrote one of his most durable pieces, Song for Che. Latterly he has recorded duet albums (notably with pianist Hank Jones on Steal Away, a profound collection of spirituals) but has also kept his Quartet West outfit going, an LA-based band which includes former Aucklander Alan Broadbent in its ranks as pianist and arranger.

Haden has performed with most of the great jazz artists of our time: Hampton Hawes, Joe Henderson, Paul Bley, Jan Garbarek, Shirley Horn, Pat Metheny on the excellent Beyond the Missouri Sky of the mid-90s, Archie Shepp, Egberto Gismonti, Keith Jarrett, Joe Lovano, Gonzalo Rubalcaba, Geri Allen...the list goes on, and as far back as 1989 the Montreal Jazz Festival organised eight tribute concerts of Haden who played with the stellar guests.

Most of those performances have been drip-fed out as The Montreal Tapes since the mid-90s, and they are almost all superb.

Oh, did I mention he also played with the Portuguese fado guitarist Carlos Paredes and has recorded albums with Quartet West which evoke the atmosphere of Raymond Chandler film noir?

Since the boundary-riding period with Coleman, Haden has become more considered and nuanced in his playing, these days preferring the less-is-more approach, which is why Broadbent fits in so seamlessly in the elegant Quartet West.

For example Broadbent appeared as an arranger on Haden’s 2002 American Dreams, which featured saxophonist Michael Brecker, the brilliant pianist Brad Mehldau and drummer Brian Blades.

American Dreams is embellished by an orchestra on many tracks, with Haden exploring all those parallel American roots of popular song (the theme from Tootsie is here), some material by past collaborators (Coleman’s Bird Food, Metheny’s Travels, Jarrett’s No Lonely Nights) and even an evocative treatment of America the Beautiful.

For a man who once berated “Amerika”, he seems to come home to the slightly sentimental traditions of his homeland. Which makes for some over-ripe lushness in places on the album, but no matter.

This is quietly probing music best considered over its complete arc. Haden’s depth of tone allows him to dominate should he wish (he doesn’t) and Brecker’s mature tone is the perfect foil.

The Coleman track (originally on Change of the Century way back in 1959) is the standout. Over its seven and a half minutes it is taken from its bouncy, archetypical Coleman head and deconstructed first by Haden, who strips it back and expands it by bending notes in the lower register before setting up a lively funk pace, then by Mehldau, who takes a pointillistic approach before opening out in a trickle of notes like water down a wall, and then by Brecker, who picks up some gentle swing-bop.

As with everything here, however, it is spare and lithe, dexterous and positively charming. And yes, there is perhaps much here which charms rather than digs deep.

But it’s unlikely you’ll hear a more engaging, emotional and considered album for quite a while -- and it is a useful introduction to Haden‘s work.

Haden brings so much intelligence to this album it is no surprise he includes Vince Mendoza’s lovely Sotto Voice (arranged and conducted by Mendoza, as is Metheny’s memorable ballad Travels).

Haden is a composer, arranger and bassist whose long career has always rewarded attention. He’s the only jazz musician working today who can put in his liner notes a quote by Albert Einstein which makes perfect sense: “If I were not a physicist I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music. I get most join in life out of music.”

Charlie Haden, who grew up playing country and western, makes daydreams come true through music. It’s a rare gift, and American Dreams - which was not been prompted by September 11 as some shallow thinkers suggested – realised them again.

post a comment