Graham Reid | | 6 min read

The only sound in this small foyer is a huge fly buzzing monotonously and occasionally slapping itself into the windows. Peter, one of the guitarists studying at this retreat in Howick whispers “are you the journalist?” and our conversation is carried out in hushed voices so as not to disturb the 20 or so people in the room next door.

Their shoes lie around the floor, and beyond the thin wall the group is apparently involved in “The Practice of Silence” according to the noticeboard on the wall.

“Are you waiting for Robert?” whispers the guitarist. “He’ll be out at seven. It’s five-to now - five minutes.”

“Punctual huh?” I quip. “Punctuality is important?”

Peter smiles knowingly, nods, then excuses himself and walks off the dormitory area. At exactly 7pm the doors open and Robert Fripp -- onetime guitarist for David Bowie, collaborator with Brian Eno on the innovative No Pussyfooting (‘73) and Evening Star (’75) albums, and founder member of prog-rockers King Crimson -- emerges.

Dressed casually, but primly, in black sweater and loose trousers, he flits a smile, deftly picks up his small bag and disappears through the trees which surround Fowey Lodge here on the edge of the harbour.

Now in his mid-40s with tightly clipped hair slightly receding over a broad brow, Fripp looks every inch the description he and Eno once gave themselves, “a small mobile, intelligent unit”.

Slowly the musicians on this Fripp-designed Guitar Craft course emerge from the room, slightly pale and grasping for news of the outside world after five days as recluses.

Rising at 6am and setting aside half-hour blocks for “The Practice of Doing Nothing” is clearly something new to the people.

In his quiet, orderly way Fripp later explains the discipline of this Guitar Craft course -- the first held in this country and at the invitation of former New Yorker Nigel Gavin and members of the 10-piece guitar group Gitbox Rebellion.

“Punctuality is a personal technique,” says Fripp whose conversation is peppered with Zen-like aphorisms. “Punctuality is efficient and saves a lot of time. A good technique is part of any discipline and it’s too easy for me to be standing by the door and closing it when time is up.

“It’s harder when one is on one’s own. Part of my work is, for a period, to play the role of the student’s better self and make the demands they would make of themselves.”

He extends the argument by referring back to when he stood by the door at precisely 8pm - the time he had earlier announced this talk would take place - and closing it on late-comers.

“There is no such thing as a mistake, save one: failure to learn from a mistake. At the next meeting one can arrive in good time -- in which case no mistake has been made. The lesson has been learned.”

If these carefully judged words and the prim appearance of the man who played “hairy rock’n’rol guitar” on Bowie’s Heroes album seem at odds with a rock lifestyle then Fripp can simply point to his past. He has more often than not gone his own way, and this child of Wimborne in Dorset has remarkably specific recall of dates and places.

He bought his first guitar at 11 (on December 25, 1957, it was a terrible instrument he says) and carefully analysed the lack of a school of thought for the functioning of the right hand.

“This was very clear, even to an intense and earnest 13-year old,” he says with a slightly mocking smile.

With Michael Giles, he formed a pop band in Bournemouth at the height of hippie days in ‘67 but within two years was at the core of the devastatingly good King Crimson.

For the next six years the band toured extensively, grew from art-cult status to stadium fillers, recorded at least two classic albums (In the Court of the Crimson King in ’69 which featured their epic 21st Century Schizoid Man, and Lizard in ’70) then self-destructed -- although there have many subsequent re-formations with various players.

Within the band Fripp’s quiet presence stood at odds with that of the other members. For Fripp, something “clicked with a very loud bang and blew the top of my head off and [in ‘74] King Crimson was over”.

He was introduced to the teachings of JG Bennett -- a disciple of the mystical philosophers Gurdjieff and Ouspensky -- and took a year’s course at Sherbourne where he studied their philosophies and dug trenches.

“In ‘74 I left the music industry for three years and went into a retreat for a year of that,” he says. “I had no intention of returning to music but I’d get a few phone calls from musicians like, ‘Hello, this is Brian [Eno]. I’m in Berlin with David Bowie. We were wondering if you’d like to come and play guitar on his new album‘

“I’d say I didn’t know if I could still do it but if they wanted me to take the chance, well . . .”

Gradually he found himself returning to playing with the people like Peter Gabriel and producing for Darryl Hall (both of whom appeared in Fripp solo albums alongside other heavyweights like David Byrne).

“Then Blondie -- who had driven around Europe listening to Bowie’s Heroes -- would say, ’we’re playing at CBGBs on Saturday, it’s a benefit for Johnny Blitz of the Dead Boy who’s been in a knife fight, do you want to come and play?’

“So I’d do those things. Then I realised I hadn’t really retired.”

And, efficient as ever, he planned his return with a series of solo albums and collaborations of considerable eccentricity.

For his first solo album Exposure in ‘79 he thought up what he now calls “a wonderful wheeze for promoting it“.

“I would play solo concerts in offices, canteens, record stores and anywhere that would have me.”

And he did.

In May 1979 Melody Maker was reviewing his performances in the Virgin Megastore on Oxford St and the Pizza Express, a fast-food outlet in Notting Hill Gate.

There was -- as always with Fripp -- a parallel purpose however.

“In ‘78 I consciously set out to learn the music industry from the business side and to discover what it was like for the people who worked in the offices. Most people go into those jobs because they like music -- but they quickly realise that is nothing to do with it.”

He tells of seeing misdirected money. Of a promotional budget of $350,000 spent on a band “that had no chance whatsoever of being successful” (but was a pet project for highly placed record exec) and of cocaine being supplied to ensure certain people were given high profile promotion.

Then, just as abruptly, with a brace of acclaimed solo albums and work with another line-up of King Crimson behind him (their ‘84 Discipline album came with the perfect Fripp title) he quit again.

Then it was Guitar Craft.

In early ‘84 he did his first guitar seminar for the course which focuses on notions of silence as much as technique.

“Music comes from silence, so musicians must learn to be silent, or at the very least, quiet.”

But all this discipline and reserve makes you wonder where Robert Fripp -- the one who was sought out by Bowie and Blondie, and once tried to meld his guitar sound with avant-garde jazz guitarist James Blood Ulmer -- has gone.

He smile benignly, pushes his modest wire-frame glasses up his nose and considers the question for an impossibly long time. The guitar students sitting in a semi-circle around him wait without movement.

“In 1978,” he says in his gently modulating and very precise voice, “the next 12 years presented themselves in four three-year stages.

“Don’t ask me why that was so, it is not a rational process -- but a musician is used to dealing with creative impulses which you learn to trust and don’t process rationally.

“So that was until 1990. I don’t know what is beyond that but my sense is there is a powerful impulse coming into the world in the spring of 1991, so powerful we can’t predict it.”

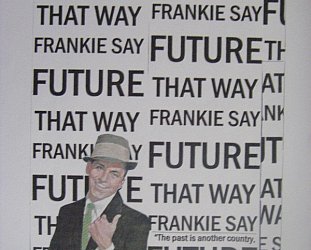

Illustration by Richard Dale

post a comment