Graham Reid | | 8 min read

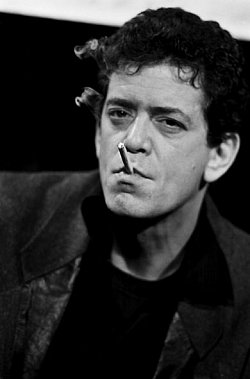

Think about it, Lou Reed shouldn’t be here in 1989. Scan his background and the death vultures were wheeling from the first time he came through with the Velvet Underground.

But all right, he’s here -- and should we still care?

Face it, his albums in the 80s have been pretty uneven, some just simply bad.

And yes, the granddaddy of punk now appears in American Express Card advertisements, so there’s his credibility blown away in a one-shot.

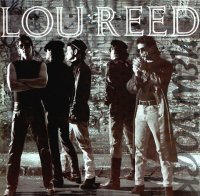

But you can’t count this man out, because just when you do he springs back with his best album in years.

New York is one of those fascinating self-referential albums, heavy with on politics, strong on poetics and -- of course -- it has been slagged by some of the more hip agents of the press.

The Sydney Morning Herald sniped it was “a classic rock critics’ album” because it supposedly shares a vision of the world (New York street life and dumping on politicians) which journalists like to think they also share.

Fair comment perhaps, but to then insist journalists tend to give priority to lyrics “because it brings the artist on to their own terrain” does a disservice to rock listeners and Reed. The man is literate. Should he hide it?

And Reed, doubtless delighted by this return to form, is out there giving interviews -- typically tetchy one, to be sure -- and reminding people of just how smart he is. He uses big words.

“The veracity of the thing,” he says referring to a song on the album about an anxious parent-to-be, “ shouldn’t rest on whether or not I have direct experience. I have a lot of friends with kids.”

And when he met Melody Maker writer Allan Jones the conversation was peppered with name-checks of his friends like post-modern artist Julian Schnabel, film-maker Martin Scorsese, and some astute, if belated, political analysis of the Reagan Years.

All of which is interesting, but can Lou still rock?

Here comes the good news. With a stripped-down band -- “you can’t beat two guitars, bass ands drums” he writes on the album sleeve -- Reed cranks up some old energies again for the broadly conceptual New York.

And on the strange metaphorical narrative The Last Great American Whale, he even nods cleverly towards his classic Walk on the Wild Side.

The sound of the album may be a look backwards to the 70s, but Reed calls the standard line-up “Lou’s Favourite Tones” and, says bassist Robert Wasserman, “goes where no bass has gone before”.

A critics’ album maybe, but chart success has followed and Reed was in Billboard with a bullet.

Yep, the old boy can still surprise, and you’ve only got to look at his erratic in the 80s to see just how much New York is a return to form.

Reed entered the decade in typical 70s-decadent fashion. His 1979 double album Take No Prisoners was a pugnacious live set with Reed squaring off jut-jawed against his audience and his songs. The album came with a sticker, “this album is offensive”. No qualification, no “may be offensive”. It is offensive.

“I wanted to make a record that wouldn’t give an inch,” he said later, and on that album after an audience members snipes at his ethnic slurs Reed opens up with both barrels.

“So what’s wrong with cheap, dirty jokes?” he yowls. “I never said I was tasteful.”

Nor diplomatic. That same year he boxed David Bowie’s ears very publicly in a Chelsea restaurant.

The following day Bowie’s new single was released, Boys Keep Swinging.

Lou, the master of timing?

It was an inauspicious entry into the new decade and subsequent albums didn’t offer much hope. Sometimes they were good enough, the old black humour still cutting, but somehow the transition from anger to adulthood seemed clumsy.

Around the time of The Blue Mask in 92 he reiterated what he was up to as he had done with his classic Berlin in 73: “I’m interested in making records as honestly as possible for adult people to listen to. I don’t make music for children or kids.”

When old literate Lou had been acclaimed as the granddaddy of punk, the ex-student of Syracuse University answered with a little Shakespeare: “all sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

With New York, Reed has brought all sides of his complicated background together. He still has a rock’n’roll heartbeat, addresses complex political ideas (Jesse Jackson’s “common ground” speech and the contradiction of his racist jibe calling New York “hymie town”) and gives free reign to his poetic inclinations.

It’s too easy to remember Lou Reed was a junkie and too easy to forget he’s had poetry published in The Paris Review.

New York reminds you of all these sides.

In Dime Store Mystery, a coming to terms with the death of Andy Warhol, Reed speaks of the philosophers Hegel and Descartes.

“Every great novelist gets a shot at the Great Why”” he told Newsweek. “Why shouldn’t I?”

There’s Reed’s framework. He’s still a man who calls rock’n’roll “a really stupid medium” and naturally prefers Raymond Chandler to Roxy Music. But it doesn’t stop him using the framework of rock to get the word out.

Chandler had a line, “he told Newsweek, “where he said a guy’s fingernail looked like the edge of an ice-cube. And I thought, could I ever even dream of being as good as that? And wouldn’t be fun if, while I did it, I had a guitar going?”

On New York Reed frequently hits the tough Chandler style -- “a cop was shot in the head by a 10-year old kid named Buddha in Central Park last week,” he sings on Hold On.

And when he speculates on having a family he says, “I’d raise my own pallbearers to carry me to my grave and keep me company when I’m a wizened toothless clod”.

In the Last Great American Whale he deals the dirt on his fellow citizens: “American’s don’t care for much of anything, land and water the least. And animal life is low on the totem pole, with human life worth not much more than infected yeast . . .”

Reed is angry, touching and, as always, very funny on New York. He’s read enough Shakespeare to know things can’t get too bleak all the way -- even Lear has his Fool.

In that dry talk-sing he has made his own, he can deliver lines like these with just the right sense of timing: “Some say they saw him at the Great Lakes, some say they saw him off the coast of Florida, my mother said she saw him in Chinatown . . . But you can’t always trust your mother”.

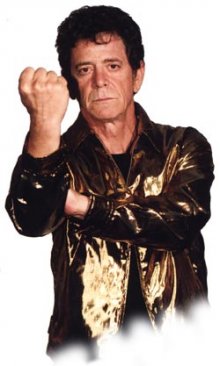

Curiously enough New York arrives at a time when Reed has a high and favourable profile.

A few years ago he appeared on the anti-Sun City song with Stevie Van Zandt and since then has become a socially committed political animal. He joined the Amnesty International tour of America in 1986 and took his place alongside Sting and U2, those great political consciences of the decade. He has appeared at Good Cause kinds of bashes in New York and rages against the Reagan legacy.

“It’s terrible what’s happened to New York in eight years of Reagan in the White House,” he told Melody Maker. “Especially when you realise it needn’t be that way. Something could be done. And the fact that nothing’s done just makes me made. You know the Reagan administration was the most corrupt American government in modern American history. And now we’ve got George Bush . . .”

This isn’t just Crazy Lou spouting off. Even that most measured of American commentators Alistair Cooke recently noted that nearly 100 Reagan appointees either resigned or were forced to resign amid allegations and charges of misconduct.

So Reed is tapping into a great vein of American discontent and the political indifference to problems like poverty an Aids.

It makes New York an uneasy listen in places.

Dirty Boulevard is a bleak image of life in a welfare hotel where “no one dreams of being a doctor or a lawyer or anything, they dream of dealing on the dirty boulevard.”

Elsewhere he rages: “This is no time for phoney rhetoric, this is no time for political speech, this is a time for action.”

All this, of course, is a long way from 1975 when he insisted songs shouldn’t have messages: “I have no right to expound my theories in my songs or give my opinions,” he said then.

But then offered the punchline: “I don’t want to hear other people’s opinions so why should they have to put up with mine.”

Reed has always been an contrary cuss and it’s encouraging to know that hasn’t changed.

Maybe what Lynden Barber says in the Sydney Morning Herald is right: “Lou Reed spent the Reagan era advertising Honda motorcycles and praising the joys of middle-aged life in the mountains,” and so these pangs of political conscience have come a bit late.

It is certainly true however the romantic gloss Reed once threw over the down-side of New York life has been shorn away on the New York album.

Whatever, this sequence of 14 songs, which Reed asks to be tackled like a movie, has thrown him back up in the credibility stakes. They also sound just fine when the stereo hits top volume and they repay careful attention.

Reed’s problem is that for many he will always be Lou Reed, ex-Velvet Underground, ex-junkie. He knows it.

It’s a problem which still dogs someone like William Burroughs. Reed has just got o stick around and hope others get it all in perspective.

But Reed has always been a contentious case, he shrugs off the praise of critics just as he shucks off their derision.

He’s the one too many writers have taken as a cultural reference point, someone -- like Lennon, Dylan and a few others among the select -- against whom people measure their lives and credibility.

Too many have placed too much on Reed’s shoulders.

The late Lester Bangs once wrote of him: “Lou Reed is the guy who gave dignity and poetry and rock’n’roll to smack, speed, homosexuality, sado-masochism, murder, misogyny, stumblebum passivity and suicide, and then proceeded to belie all his achievements and return to the mire by turning the whole thing into a bad joke.”

New York may not have entirely convinced Bangs -- but dignity, poetry and rock’n’roll are firmly in place about a whole slew of socially uncomfortable topics.

It’s a pity Bangs didn’t live long enough to hear it.

After all, he was warned.

Ten years ago Lou Reed got it in one when he said, “I’m a long-term player.”

And he’s still here.

post a comment