Graham Reid | | 4 min read

A true story from the battleground of fun: a few fortyjust wags finishing last bottles when someone mentions an album title which reduces the gathering to choking laughter for a good two minutes.

As someone observed later, “it’s some album when just the title breaks you up.”

True – but the album in question wasn’t actually that bad. “Their finest so far, evincing a discernible new style of some compositional activity making full use of the group’s greatest assets...” said The Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Rock.

The album?

Larks’ Tongues in Aspic, the ’76 album by English “progressive” art-rockers King Crimson, who – with guitarist Robert Fripp their sole constant – hobbled their way though the late 60s to mid-70s.

With their albums remastered by the diligent and posterity-conscious Mr Fripp, KC are worth a few minutes of anybody’s time.

Sometimes, unfortunately, very few.

The laughter over Larks’ Tongues however wasn’t specifically directed at the album or the band, more at what they represented: ambitious often pretentious music of the kind the arrival of the Sex Pistols dealt a death blow.

These days it’s easy to point the finger at KC buy calling it self-indulgent – but isn’t all music? Mr Lydon indulged selfishly. So let’s get that accusation out of the way.

The big knee-capper with early KC was the lyrics by Pete Sinfield, an on-again/off-again member with the uncanny ability to write astonishingly pompous nonsense. Call it a gift if you will; this boy was bad. But not always.

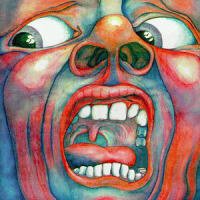

The KC debut in ’69, In the Court of the Crimson King, still stands up well. Impressive Fripp power chords and weedlingly melodic mellotrone and a whack of sax from Ian McDonald, all in a brutally ugly gatefold cover (always a plus when parent baiting) which small CD reproduction can’t do justice.

Sure, there was some rubbish within (the earnest Epitaph) but the band’s crunching weightiness in the title track was the perfect amalgam of Tolkien and a tab.

It doesn’t exactly rock, but then again KC – like Zappa, Can, Eno and others – were never quite rock, just part of its culture.

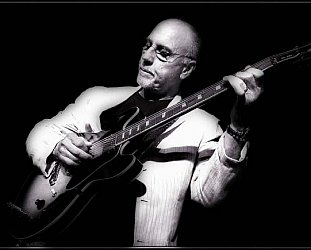

When McDonald and drummer Mike Giles quit after “a gruelling 11-day US tour” (Gruelling? Tell it to B.B. King, man), guitarist Fripp – who sat down when he played, so how gruelling was it really? – was forced to rebuild the band. It wouldn’t be the first time.

As a result, the second album, In the Wake of Poseidon in 1970, was a pallid, more twee re-run of the debut, although it was easy to make a case for the uncharacteristically rocky Cat Food which lifted heavily from Lennon’s Come Together.

Like all KC albums, it wasn’t without its high points...or duffers.

But constant line-up changing (which made the Chills look mere novices at the “musical differences” press release) effectively nobbled the band for the next four years until Fripp officially blew the whistle in ’74.

They had, in their various forms, released an album a year to mixed reactions. People loved ‘em or hated ‘em. Or more correctly, worshipped or despised them.

With the advantage of 20/20 hindsight, it is easier to pick directions and highpoints in the band’s brief but influential career.

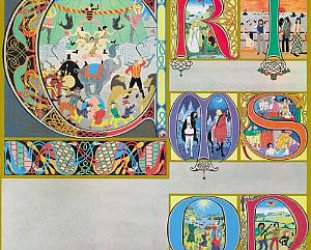

Lizard, from December ’70, was a considerable advance over Poseidon Fripp’s Bolero track pushed profitably into jazz of a free, loose kind (the line-up included pianist Keith Tippett and adept saxophonist Mel Collins), but, typically, reviewers were divided.

“The perfect record for the person you like least,” sniped the London Evening Standard; “a flowing flexible marriage unfalteringly stepping from one idiom into the next,” wrote NME generously. They were probably both right.

Lizard (the subsequent live Earthbound more a holding action), Islands from ’71 and (giggle) Larks’ Tongues vindicated Fripps’ vision of a band that bridged rock, jazz and The Big Statement. He was also increasingly and mercifully shot of Sinfield’s lyrics.

The problem then – and even today, if drunken fortyjusts are to be believed – was that they were dumped in alongside lumpen dolts such as Gryphon, Renaissance and various Dutchmen With Attitude (and usually a sociology degree).

After Fripp called it off, he unveiled Red, seductive in parts but mostly unengaging and evidence the band had run its course. By then they were up to about line-up nine in five years.

But Fripp was unable to entirely disengage himself and after a couple of classy collaborations with Eno (two more scrupulously exact intellects you couldn’t find) and work with Bowie, he resurrected the band name in ’81 with the most stable line-up ever.

For three albums – Discipline, Beat and Three of a Perfect Pair – with bassist Tony Levin, drummer Bill Bruford and guitarist Adrian Belew, they pursued a different style.

Discipline and Beat were appropriate titles for albums that offered perfect renderings of precise, sometimes soulless, guitar asceticism. Beat might have entirely missed the passion and energy of its theme (Kerouac and Cassidy/On the Road) but, taken together, the three albums were the most satisfying of the KC – in the name only – catalogue.

Must’ve been the Discipline.

So, King Crimson? A bunch of public school (private school) wallies? Perhaps. A rock band? Not really. A grand conceit by Fripp, a man prone to smug aphorisms? Undoubtedly. How best to check them out, then?

Fripp – ever helpful – compiled A Young Person’s Guide to King Crimson in ’76 (bit dodgy) and The Compact King Crimson in ’86 (much better). Then came the inevitable, four CD box set, the exceptionally beautiful/arty/thorough and quite superb Frame by Frame, which came with a courageously honest 64-page booklet which included unfavourable reviews alongside the slavering raves.

If the budget allows it, Frame by Frame is the way to go, all you needed to hear.

But then you’d miss the necessary unevenness of that (titter) debut, the (snicker, chuckle) Lizard/Islands period or the (guffaw, haha) full effect of (hahaha) that interesting (hawhawhaw) Larks’ Tongues in Aspic.

Hahahahahahahahahahahaha.

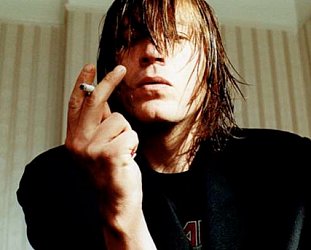

Robert Fripp illustration by Richard Dale

post a comment