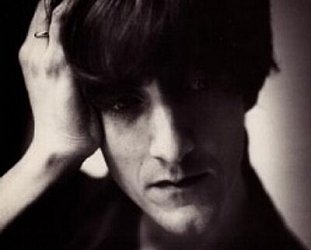

Graham Reid | | 6 min read

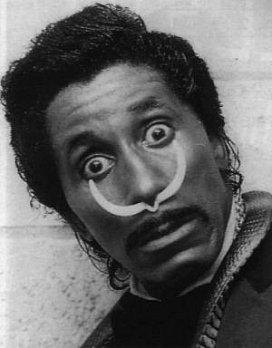

The man on the phone with the curiously quiet voice gently sets the record straight quite quickly. He’s never considered himself a singer he says. But after 35 years of making records and giving the world one of the most outrageous stage shows ever, then what is he?

“I’m a big mouthed screamin’ man who uses a lot of flamboyance in his shows,” he says seriously.

Well, the first part of that is certainly correct. Anyone who has had part of their skull severed by his astonishing I Put a Spell on You, She Put the Whammy on Me or, even better, the hacking, primal roar and pain-ridden torturing of Poor Folks would agree. Yes, this is the work of a big mouthed screamin’ man.

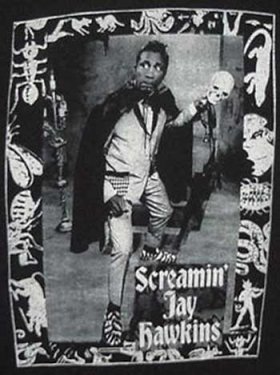

But somebody who uses a lot of flamboyance in his shows? That seems just a little understated.

After all this is the man who crawls out of a coffin, carries a skull on a stick, pokes the voodoo magic, has been known to perform with live snakes (rumoured to toss them into the crowd) and generally set new thresholds in outrage. And he started doing that in the mid 50s when Doris Day kissing on screen was a Real Big Deal.

What do you call this kind of thing? “Flamboyant“?

At the very least.

Call it Screamin’ Jay Hawkins and believe the hype. This man is in the inventor of Hoodoo Blues, is hailed as The Wildest Man in Rockn’n’Roll and while Little Richard was trying to decide whether to be a rocker or a preacher Screamin’ Jay was pushing his voice -- and audience – to the limits of tolerance and excitement.

The man who sings Baptize Me In Wine, I Found My Way to Wine and Constipation Blues tells a fine story. Consider this one about the recording of that shattering song I Put a Spell on You which featured on the soundtrack to Jim Jarmusch’s ’84 movie Stranger than Paradise and made Hawkins a cult hero all over again.

“The producer says, ‘How do you act in nightclubs?’ ‘Like any other entertainer.’ ‘Do you drink?’ ‘Yes, I drink.’ ‘Do you get drunk?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘Do you go onstage when you’re drunk?’ ‘Yeah.’ ‘How do you sound when you’re drunk?’ ‘How the hell do I know, I’m drunk, I can’t remember.’

“So he went out and got a case of whisky and got me drunk, the whole band got drunk and then we recorded I Put a Spell on You.”

Hawkins may not get drunk quite so often these days but at sixtysomething he hasn’t slowed down at all.

Born in Clevedon in 1929 as Jalacy Hawkins, he came late to music. He grew up with as much light opera and jazz in his listening as the sound of blues and swing dance music. A little formal training on piano, some rudimentary saxophone and then it was into the Air Force until 1952. When he emerged he hung out with tough tenor saxophone players like James Moody, Arnett Cobb and Illinois Jacquet.

His first professional gig was with guitarist Tiny Grimes, a kilt-wearing showman whose Rocking Highlanders had briefly included the up-and-coming saxophonist Charlie Parker.

It was with Grimes’ band that piano-playing/saxophonist-singer (and chauffeur) Hawkins first started to emerge as a stage presence. It was also the cusp of the rock’n’roll era.

Conventional wisdom today says Hawkins’ formative years around Cleveland -- where no particular musical style predominated -- accounted for his development as a stylist unaffected by influences. Hawkins discounts that.

“A lot of fine artists came for Cleveland,” he says. “The Platters were from there – and Fats Domino was playing around there. And Alan Freed started there, we called him ‘Moondawg’ in those days and he was the first to put on black and white performers together.”

Freed’s role in the history of rock is well documented. A radio DJ (“we thought he was black,” says Hawkins), he knew Hawkins and when he heard the re-recording of Spell – the blind-drunk 1956 version – he put Hawkins on the bill of his live shows.

Freed encouraged Hawkins’ outrageous performances but when the payola scandal came along and Freed was fingered (“they hounded that man to death”) – Hawkins’ name was inevitably linked. The question was simple: how could such a bizarre scream-fest as Spell get on radio if a DJ hadn’t received money to play it? Nobody surely liked that stuff, did they?

They did – and Hawkins career continued despite a conservative white lobby which thought his “savage” music was corrupting the youth – and the black National Association of American Coloured People (NAACP) which took him to task for demeaning and parodying blacks. The bone through the nose was what did it.

Now, as he did then, Hawkins defends his actions as those of an entertainer and pins the argument on to the NAACP itself.

“An entertainer’s position is to entertain and be an individual. Like Tiny Grimes wearing a kilt, Dizzy Gillespie and his hats. Yet the NAACP came after me when they don’t even know who killed Malcolm X and still haven’t found the truth about who killed Martin Luther King.

“Why come after an entertainer when there are so many other things they should be looking at?”

And regardless of the criticism, Hawkins continued to perform – not always to huge crowds admittedly, but performing nevertheless.

In time he spawned the inevitable crop of imitators.

Few would be so courageous as to cover his songs (although Alan Price a surprise hit with a courteous remake of Spell) but the “flamboyance” of his shows could be seen in The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, Alice Cooper whose nightmare and snake act was clearly drawn from Hawkins and, more obviously, England’s Screamin’ Lord Sutch.

Hawkins says he is flattered by being imitated although he has spoken with Arthur Brown over lunch and posed the question: if your are imitating me who are you going to imitate when I’m dead?

These days Hawkins says he is as busy as ever. He has homes in Hawaii and California which he seldom sees, and ironically for a man whose appearance in the ’57 movie Mister Rock And Roll ended up on the cutting room floor because it was considered in bad taste and racially insulting to blacks, he is in demand for movies.

He dismisses his cameo in Jarmusch’s Mystery Train where he played a hotel keeper (“I just got to wear a red suit, they wouldn’t let me perform”) and hasn’t even seen some of his more recent screen efforts.

Yet for all his outrage, controversy, multiple banning and censoring. Other than a wandering eye when it comes to the ladies -- he has dozens of children to as many mothers -- Hawkins is scrupulous about keeping clear of the obvious temptations of his lifestyle.

He was even careful about his reworking of Paul McCartney’s Monkberry Moon Delight back in ’71 -- a song McCartney clearly wrote in the Screamin’ Jay style -- because of a reference to “pillow up my nose” in the obviously nonsense lyrics.

“I am very cautious about what can touch my name or surround me,” he says. “I stay away from the people who cater to those things in this life. If you lay down with dogs you come up with fleas and in my life I have always been clean and free of those temptations.”

But how does a man who makes the demands he does of himself survive in an industry and lifestyle which is so often one of dependency and addiction?

“It’s easy. I watched Clyde McPhatter die, I watched Frankie Lymon die, I watched Ike Quebec die, I watched Gene Ammons die. I watched and learned and vowed never to repeat their mistakes.

“You have to work for opportunity to knock and if it does you have to be able to hear it. You have to always be alert.

“You come into this world naked and broke . . . and you go out naked and broke, but you have to live along the way, you can’t go on wallowing in a barrel of rotten apples.

“I’m an entertainer giving 100 per cent. To give, you have to be prepared all the time.”

Hawkins sounds prepared. It’s just that every now and again someone has to warn his audience.

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins died in February 2000.

post a comment