Graham Reid | | 4 min read

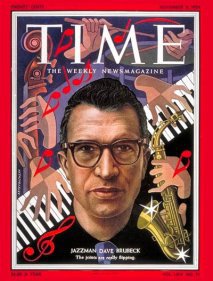

Time. It marched on. Dave Brubeck lived to a fine old age in jazz where unemployment, insolvency and lifestyle usually takes its toll much earlier. In his obituaries Brubeck could reasonably expect tributes for popularising jazz with American college students in the Fifties, appearing on the cover to Time magazine in 1954, releasing one of the most durable and popular jazz albums of all time (1959’s Time Out) and throughout his career experimenting with time changes.

Time. It had been the recurring theme in Brubeck’s career. But so too had been critical derision, although this last decade or so a career reappraisal happened.

Sony’s excellent and reasonably thorough overview of Brubeck’s music, Time Signatures: A Career Retrospective, released in 1992, was a turning point in challenging the consensus. This four disc set opens with a recording form 1946, which features clarinettist Bill Smith as a member of Brubeck’s octet, and closes with a Smith-Brubeck duet on ‘Stardust’, recorded in 91.

Between times – whether it’s Brubeck playing a duet with Charles Mingus, laying down chords behind Louis Armstrong or in previously unreleased live sessions for Moscow in the late 80s – it mounted an impressive case for the defence. And since then there has been a necessary, overdue critical reconsideration.

The Eighties edition of The Penguin Guide To Jazz on CD opened with this on Brubeck: “Often derided as a white, middle-class formalist with a rather buttoned down image and an unhealthy obsession with classical parallels and clever-clever time signatures, Brubeck is actually one of the most significant composer-leaders in modern jazz.”

That’s one in the eye for the New Yorker’s critic Whitney Balliet who wrote in 1971 after a Newport Jazz Festival appearance, “there is no need to worry about Brubeck anymore. He is what he is – a jovial amateur pianist who happened along at the right time with the right music and make a million’.

That was typical of what Brubeck endured most of his career.

Although to be fair to that critic, the Seventies weren’t good years for Brubeck in jazz. (Tellingly Time Signatures includes only three tracks from the decade). But Brubeck had moved elsewhere.

His quasi-classical jazz written in the late Sixties was extended in the Seventies, although he still managed to play alongside Lee Konitz and avant-garde saxophonist Anthony Braxton in ‘73, neither of who brought the critical line obviously. And that’s the key to understanding Brubeck; his successes in the 1950s allowed him full rein to explore other areas.

His quasi-classical jazz written in the late Sixties was extended in the Seventies, although he still managed to play alongside Lee Konitz and avant-garde saxophonist Anthony Braxton in ‘73, neither of who brought the critical line obviously. And that’s the key to understanding Brubeck; his successes in the 1950s allowed him full rein to explore other areas.

By inclination and education he was lead to a kind of jazz academia, but lived comfortably with jazz of the black/blues base. In January 1960, the day after recording with bluesman Jimmy Rushing – at the singer’s request – Brubeck and band were back in the same studio with the New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein. He also wrote music influenced travels in Japan (Fujiyama, Koto Song), sacred texts and Spanish sounds.

Brubeck’s life, recounted in an excellent essay in Time Signatures, began on his parents California ranch where he rode the range roped and rounded up cattle, and learned Indian songs from ranch hands. It wasn’t until his senior year at college that he taught himself to read and write music, up until then he’d learned and played the classics and jazz by ear.

They allowed him to graduate on the condition he never teach.

Arguably, through his great quartets – and notably those with long time band member, the alto saxophonist Paul Desmond – Brubeck did more for jazz education colleges than any other musician of his time. Yet he wasn’t so much a populariser as one who constantly extended the contract of jazz. Bebop might have ruled, but Brubeck had studied with French composer Darius Milhaud and brought complex compositional ideas into jazz.

Like the ECM label in the Seventies that found its audience in predominantly white intellectual circles, Brubeck’s initial appeal lay less on the bandstand than in the bedrooms of student flats.

When he made it to the cover of Time critics said Duke Ellington should have got there first. Brubeck, embarrassed by the coverage, agreed. The critics’ complaint should more fairly have been laid at the feet of Time’s editors, but from then on Brubeck, a white guy in black music, wearing geeky Buddy Holly glasses, couldn’t win. All he could was continue to play.

Time Signatures provided ample evidence he played brilliantly at times, often letting the musical personalities of his colleagues (notably Desmond with whom he had a testy relationship) take pre-eminence. But he grew as composer and experimentalist, although never turned his band on jazz standards and the music of greats like Ellington.

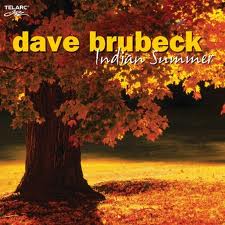

He continued to play into his 80s and in fact his Indian Summer album of 2007 -- recorded two days after injuring his leg -- was a quiet career highpoint for its thoughtful and wistful intimacy. Brubeck was 86 and did each piece in just one take.

He continued to play into his 80s and in fact his Indian Summer album of 2007 -- recorded two days after injuring his leg -- was a quiet career highpoint for its thoughtful and wistful intimacy. Brubeck was 86 and did each piece in just one take.

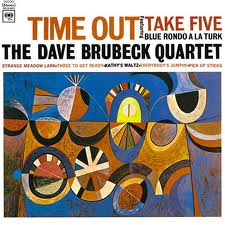

Naturally however interest always returns to that Time Out album. While its long shadow has to often fallen over the rest of his career – Time Signatures redresses the balance, only four tracks are included – it is album of inarguable invention.

But maybe that’s just me. As a kid I first heard it as an ineffably cool sound drifting up from the flat below. It sounded like the happiest thing ever.

I somehow got a copy and played it until the grooves were worn. The track Take Five explained jazz to me in one sitting: the way a piano and bass could interlock, how a drummer could shift time (hats off to you, Joe Morello) and how a solo can be improvised. That’s big stuff when you’re in primary school.

Almost 50 years on I’ve still got that same thick piece of vinyl.

The music hasn’t become obsolete either. Both, unlike the opinion of Brubeck’s contemporary critics, have stood that most difficult of tests.

Time.

There is more -- and more personal -- about the late Dave Brubeck at Elsewhere here.

post a comment