Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Wayne Shorter: Face of the Deep (from The All Seeing Eye, 1965)

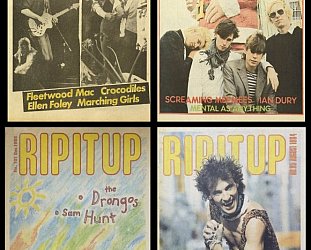

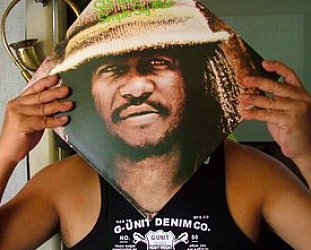

When my eldest son bought a one-way ticket to London and packed his bag, he brought over three boxes of vinyl for me to store. Over the weeks I picked my way through this eclectic treasure trove admiring his excellent taste, sometimes wondering where I had gone wrong (the Joey and John Travolta albums, were a joke, surely), his bizarre acquisitions (Spiderman and Wonder Woman albums?), and light-fingeredness (so that’s where my Joy Division went).

It was fun (the David Hasselhoff album recorded at Mandrill in Auckland) and also slightly nostalgic (why don’t I listen to the Fall anymore?).

I also discovered a few albums I once enjoyed but hadn’t heard since they disappeared in his direction. Among them was saxophonist Wayne Shorter’s Atlantis from 1985, which I banged on again.

It opens with the sound of 80s synth-jazz, a kind of pre-programmed jazz-light feel is perpetuated throughout and Shorter seems bereft of new ideas. A couple more plays and these impressions fade a bit – his playing is typically excellent, but it is still far from his best. Shorter turned 70 in 2003 (he looks alarmingly youthful still) and he’s still making albums but is – as with his bandmate in the seminal Weather Report, keyboardist Joe Zawinul, and long-time friend and collaborator Herbie Hancock – probably not much listened to by many these days.

Not even by those who remember when he was widely considered the heir to the John Coltrane/Sonny Rollins lineage and crashed onto the jazz scene in the 1960s.

After studying music for four years in New York in the early 1950s, Shorter joined the army for two years then started his jazz career in Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in 1959. He played alongside Miles Davis for six years until 1970 (during which time he recorded some of these finest albums under his own name for Blue Note and matured as a composer).

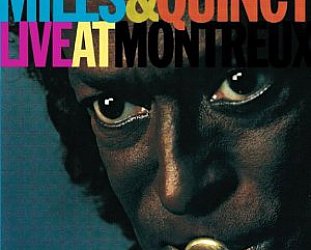

His work with Davis during this period can be heard on great albums like Live at the Plugged Nickel and he wrote some of Davis’ classic material: ESP, Dolores, Footprints and Nefertiti among them.

In 1970, he co-founded Weather Report with Zawinul after they both left the Davis band, and for the rest of that decade they were the most influential group in jazz. Their exploratory and inventive albums were as eagerly anticipated as any rock groups, and they had a sizeable rock following in those days when the boundaries sometimes blurred between the two. In their ranks they also had the fleet-fingered bassist Jaco Pastorius who had rock star looks and was a genuine genius on this instrument.

When Weather Report folded in the mid 80s after a couple of disappointing albums, Shorter ambled into the 90s and seemed adrift. He made albums that touched on fusion and funk, sometimes had Brazilian influences, but he seldom captured the magic he once conjured up with apparent ease. Some said his compositional abilities were at their best when he was in a stable group as with Davis or in Weather Report, where he could write for the specific voices in the band.

Whatever, Shorter largely slipped from the jazz consciousness during the early 90s. His thoughtful High Life (1996) – his first for the Verve label –went almost unnoticed until it won a Grammy. Until then, we might have through Shorter’s career would go into a stately decline. All it needed was the tribute album (thank you Rachel Z, the acolyte who orchestrated High Life and delivered one) and the reissues which Blue Note obliged with, among them Speak No Evil, The All Seeing Eye and Juju, which should be in any serious jazz collection.

Perhaps it was these late 90s reissues which alerted the world to Shorter again, but he certainly made good on the promise of High Life. His 1997 acoustic duo album with Hancock, 1 + 1, was gorgeous and its tribute track to the Burmese political leader, Aung San Suu Kyi, won him another Grammy (Best Instrumental Composition).

In his late 60s, Shorter was producing some of the most considered music of his career, and he solidified his position with Footprints Live!, that prompted Amazon.com reviewer Eugene Holley Jnr to declare, “Wayne Shorter is a jazz god, and these are his sacred sonic scriptures”. Well, maybe.

With much the same group – pianist Danilo Perez, drummer Brian Blade and bassist John Patitucci – Shorter released the excellent, diverse Alegria in 2003 (his first studio album in eight years) which reached back to his Blue Note and Davis days for some of the material – Angola and Orbits got substantial reconsideration; Capricorn II was a sequel to ‘Capricorn, which appeared on Davis’ Water Babies – and it dipped into Celtic music (She Moves Through the Fair).

There were Spanish stylings (Vendiendo Alegria) and medieval music (12th Century Carol), but only one new composition, the straight-ahead light bop quartet setting of Sacajawea, which many said wouldn’t be counted among his better originals.

But elsewhere this was an often delicately sculpted album which invited in cello, bassoon and clarinet where required. And Shorter’s playing was undiminished by his years.

The same year Wayne Shorter was honoured with a Carnegie Hall concert, then a tribute to him on his birthday at the Hollywood Bowl with Hancock, Joni Mitchell (Shorter has played on many of her albums) and others.

Alegria won him another jazz Grammy (Sacajawea picked up best instrumental composition).

It’s encouraging that, unlike some elder statesmen of jazz, Shorter is deserving of such accolades, not for that illustrious past but for the innovative music he has been making for this last decade.

Now you can’t say that about Joey and John Travolta can you?

post a comment