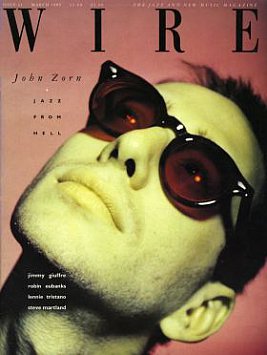

Graham Reid | | 5 min read

John Zorn doesn’t sound like your typical New Yorker. His speech is slow and measured, not quite the expected machinegun rattle of words. Then again, composer and saxophonist Zorn is no ordinary New Yorker – and no ordinary composer either.

Take his two most recent albums as a sampling from a career which has seen him come screaming from the sidelines as “avant-garde composer” into the mainstream, where his records now sell in healthy numbers, his concerts are sell-outs and his picture appears in articles in the New Yorker with captions like “the most interesting and influential composer to arise from the downtown avant-garde in 20 years.”

Hmmm, that’s serious talk – and Zorn’s music is serious stuff. His Spy V Spy album was a nuclear meltdown of old jazz tunes by Ornette Coleman played with the clenched teeth attitude and style of hardcore thrash. It was aggressive, loud and fast.

And his most recent album, Naked City, hammered home the hardcore, deftly slipped sideways into re-interpretations of film soundtracks (much like his earlier The Big Gundown,, which reworked Ennio Morricone tunes) and included short stabs of pure volume-thrash noise. “Noisecore,” as Zorn calls it.

For most of his career Zorn, now 37, has been alienating one kind of audience and gaining another. Right now the very hip avant New York scene is shying away a little from the noisecore stuff, much like the jazzers of earlier times shuddered, when he didn’t perform to their expectations either.

But funnily enough, he’s still on the bill at jazz festivals. He knows why.

“The Naked City band members are all so busy we don’t get to play together a lot. We go out about three times a year for a couple of weeks through Europe, the States or Asia and that’s it. Next week we’re playing the Montreux Jazz Festival but the jazz thing can be a drag.

“I learned a lot from that music – but I also learned a lot from other music’s. Personally I think it’s a shame we always get put into jazz festivals just because they need someone to make trouble or cause a controversy – and that’s my role at these festivals.

“The audience always wants to hear Art Blakey and Max Roach, and then I come on and they can’t figure out what’s going on. It’s okay for a while – but after 15 years of being in that position. I’m sick of it. That’s why the Naked City Band is going to record a whole lot of short noisecore pieces soon, to try to attract a more hardcore rock audience.

“I’ve been listening to hardcore for about 10 years and people doing it now are putting together music in different ways. People in the jazz idiom are less interesting these days.

“There’s very conservative backlash in jazz and they seem to have forgotten the revolution that happened in the 60s with, people like Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor. Jazz listeners now put all that into the trashcan and get uptight about how you should be playing on chord changes. I find that sad and don’t want anything to do with it.

“Albert and Cecil and all the free jazz players of the 60s appeal more to the punk hard core crowd.”

In that opinion, Zorn seems right on target. Henry Rollins of Black Flag is a fan of Ayler’s free blowing unstructured style, and so is Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth.

The revolutionary music of Ayler and Coleman, of course, alienated as many then as Zorn’s noisecore has now, and critical reaction from the mainstream jazz press about Spy V Spy has suggested Zorn is a mere dilettante who is playing with the work of a master to no obvious purpose.

“Most of the jazz people who heard that record were very insulted but there is a clear connection between the energy music of the 60s and hardcore punk in terms of energy, sound and tension.

“I played Ornette’s music for 15 years, ever since I first picked up a sax. He completely changed the way I thought about music and I worked very hard on that record.

“I figured I was only ever going to make one record about Ornette in my whole life, so I put everything into it. I didn’t whip it off as some cheap idea – but some people aren’t willing to give the benefit of the doubt because they see me as always working on different projects. That makes it too hard for them to understand.

“If I’d done the same thing year after year maybe they’d get the idea, but who needs that? They say I have no focus or move on without thinking about things – they just don’t understand.

But if that sounds like Zorn is whinging, far from it. His tone is one of weary resignation that some critics and listeners only hear the disparate nature of his work and not the continuity.

He points to his background in film and performance art scenes in New York during the 70s which give his works a theatrical, dramatic context. He points also to his first major recordings. The Big Gundown, and more recently Spillane (a kind of aural film-noir) as being part of the continuum.

He acknowledges his work has a political subtext and in the mixing of genres and styles he is saying “all these things are the same and there’s no hierarchy in music.”

That “musical cuisinart”, as one writer called it, makes Zorn’s work hard to market and denies its potential as a fashion accessory or commodity.

“I’m lucky it can’t become just another thing in the market-place because when you start dealing with artists like Madonna or whoever, people aren’t listening with their ears. They listen with their eyes and it’s just another fashion. It’s like mind control. You are told what to like with that stuff.

“With my music people have to make up their own minds and think a bit.”

If Zorn is engaged in some sort of battle against the corporate marketeers, he seems to be winning. His records sell in increasing numbers and critical and popular opinion are swinging in his favour.

He’s always going to be a minority taste – he appreciates that – but his recent Naked City album conveniently ties up the threads of the last few years in its scanning of soundtracks, noisecore, jazz and rock.

Somewhere down the line will be another Naked City noisecore album, his New Traditions in East Asian Bar Bands release (“It’s a bit too hard to explain but basically it is a series of compositions which allows musicians to improvise in a new way”) and something in the long term using Tom Waits to narrate a piece which will include the strange handmade instruments of composer Harry Partch.

All of which sounds typically Zorn – a wayward idiosyncratic path through styles which once again must give a headache to his tolerant record company.

“Record companies thrive on artists doing the same thing over and over. But it’s give and take with my company and there’s always a lot of discussion. But they’ve been good had have let me go where I want to. Even if they haven’t like the music they’ve been helpful and supportive – and that’s rare.

“But,” he laughs knowingly, “I still have to get in there and pitch it to them from time to time...”

post a comment