Graham Reid | | 7 min read

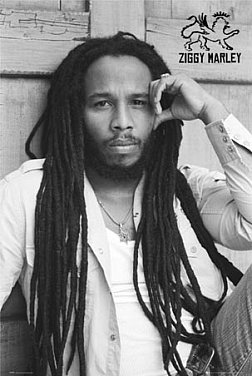

Ziggy Marley: Look Who's Dancing (Jazzie B remix)

Ziggy Marley’s throat is dry and he sounds tired. It’s nearly midnight at the Mayflower Hotel in New York and a day of photo sessions and interviews is almost behind him. But he’s going back to Jamaica soon – back to Tuff Gong Headquarters, his father’s home in old colonial style which now houses the Bob Marley Museum.

These days Ziggy Marley spends little enough time at home in Jamaica. The demands of touring take him across Europe, America and occasionally to Africa. But now it is time to rest up before a tour through Japan, Australia and New Zealand.

“Just finished a college tour,” he says earnestly in the lilting clipped JA patios. “I like to spend more time in Jamaica but now I can’t. I have to go and work. Sometimes I get very tired...”

As the son of the man Judy Mowatt recently acknowledged as “the king of reggae – the reggae ambassador,” there must be enormous pressure on 21-year-old Ziggy. He shrugs it off – but speaks with measured gravity. He knows that to many he is the bearer of some flame and the one who keeps the spirit alive.

But that ignores the evidence.

Ziggy Marley, with his sisters Sharon and Cedella and brother Stephen, have their own music. As recently as a couple of years ago Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers (as the band is called) were easily, but even then unfairly, dismissed as pale shadows of the guiding spirit.

The Conscious Party and One Bright Day albums changed all that. With Ziggy’s name pushed out front and backed the Chicago-based Ethiopian band Dallol, suddenly it was time to pay serious attention, especially as Marley combined the reggae pulse with African sounds.

“I been to Zimbabwe and Namibia for the independence celebration,” he says, “and some other places in Africa. But I live in Africa because I live in Jamaica and that is black people. Black people are the same everywhere so I don’t separate Africa and Jamaica

“But in Africa they play reggae different and have an African feel. But that is something I like to do – to explore the roots more.”

In the course of a 20-minute conversation, this is something he returns to again and again. The heritage is out there, he says, and it must not be lost. His voice is soft and remote, the words come with slow deliberation. And he feels particular unhappy that as a young man growing up in Jamaica – and going through the ordinary school system – he was taught nothing of black history.

“Nah, them teach nuthin’ of the ‘istory in school. They taught Caribbean History,” he says mocking the course title. “They teach slavery and Columbus, nothing ‘bout the African story. But, mon, consciousness is on the rise – it is on the rise.

If that is true then Marley and the Melody Makers can take some credit. Black My Story on Bright Day (written by Ziggy and Stephen) plays similar lyrical games as some of his father’s songs as it offers “black my story, not his-tory.”

Link that to Dallol’s lively step and the song places itself easily into the company of some of his father’s later songs. And pull together the other snappy, thoughtful originals the Melody Makers have, toss in a couple of long grooves to lively up yourself and music by these Marley’s takes on a life of its own.

If quality is a consideration, then Ziggy and the Melody Makers may not disappoint in concert. They also give quantity. Any promoter will tell you of how artists’ contracts state a maximum playing time. This one states a minimum.

“It’s a long show sometimes and we do songs from us from right back,” he says before acknowledging the guiding light which is ever-present.

“My father’s spirit’s is still alive and you have to let people know that. And we do songs that people know - they know my songs now, but the more popular ones are my father’s like Get Up Stand up, Could You Be Loved and War, you know.

“And there is a young generation now who don’t even know who my father was. These youths don’t know as much as the older generation, so it is important to keep these songs alive.

“You should always have respect to the people who come before like my father, Marcus Garvey and other men too. That is our heritage also. We are the people,” he says solemnly.

“But we are not too mindful of the task. We are just doing what we feel like at the time. And so far, so good. Now we are trying to get into some new things.”

For Ziggy Marley, one of the new things is his own record label, Ghetto Youth United, which he has established in Kingston and which echoes his father’s involvement in recording younger musicians on his own Tuff Gong label.

“We try to get some of the youths to make their own music but I don’t get much time to do it. I’m always away. It’s only in Jamaica for now and hasn’t got big yet because we are on the road too much. It not had a chance to settle down and get started – but I like every kind of music...”

Every kind? American pop?

“Oh not everything,” he says laughing for the first and only time. “Soul music is a good thing. And reggae – I like Dennis Brown and some oldies like Alton Ellis. I listen to those things to find out about them.”

But again he returns to the point of having so little time. When the interviews are to be done, he is the one everyone wants to speak to – but that has been a direct result of his name being pushed out front perhaps?

“That’s right, mon, but that’s not a pressure on me. We’ve been doing this from when we were young and we do it because we want to. That name means nothing to me. It’s all the same – but it helps people identify the band, right?”

That last comment shows a keen sense of business smarts, however, and Marley, after firing a shot at his previous record company (“dem do nuthing”) says things are getting much better now. The promotion is all taken care of these days so people are getting to hear the music.

But the other side of that coin is the tiredness he now feels after a long day of promotion. What is on his mind most is going home.

I’m going home to relax, get back me strength, eat good food and ready myself for what comes next. To relax I stretch and exercise, I read Scripture too.”

The Jamaica Marley and his family return to is – according to Judy Mowatt – still rife with violence, gun culture and political factions. But Marley says he avoids the obvious political grandstanding so common in music these days.

“We don’t deal with that thing – not directly anyway – but sometimes we get involved. When you deal with people from all over like we do then we have something to say. But sometimes I mean something and the lesson is understood.

“But what people write about is just what they understand. It’s shallow, shallow. You have to think about more than what you hear in the music. You have to read in between and underneath and over.”

But there’s a trap in that too. At the bottom of the One Bright Day inner sleeve is the inscription Daniel 89. Some kind of reference to the book of Daniel in the Old Testament? The delivery of Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego from the fire of Nebuchadnezzar?

“Nah, mon. That’s me son – he was born in 1989. But what that means to you, it means to you – but what it means to me is different. You take out what it means to you and you can get message in that way. That is a good thing.”

Marley barely breaks his aloof, slightly imperious manner to find humour is the well-intentioned gaff. He approaches every question with a seriousness which is perhaps the result of the shadows which swirl around him.

To come out from under the deepest shadow of his father hasn’t been easy but the recognition is starting come. After a faltering start this Marley is finally reaching deeper lyrically and wider musically. Stephen Marley even adds DJ style to their work.

“Now you have to sing and DJ together because the youth is used to the DJ and you need to give them something new everytime. It makes it a better thing for us to look at that style because we must grow in all those ways too.

“But our music is reggae and it comes to us from our life and is our hearts. But a lot of the reggae musicians don’t dwell with the spiritual things. That is what it is, you understand, mon? It is the spirit thing.”

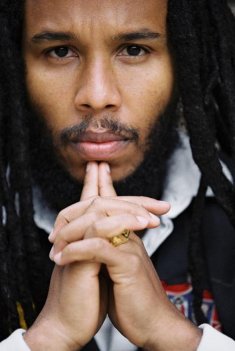

The spirit is on the rise, again with Ziggy Marley and the Melody Makers, whose huge touring party contains some interesting names. As well as bringing their own chef with them and tutor for Stephen, who is still in high school. Rita Marley will travel with them and the band includes ex-Wailer Tyrone Downie on keyboards. Jamaican guitarist Earl “Chinna” Smith is also in the band.

“This is not a new band, just different. You understand? Just another different thing, mon.”

His voice gets weary and the pauses longer between the words. Somewhere in the room at the Mayflower Hotel a voice calls him and he gets distracted. Time to let this one go.

“It is time,” he says in a hoarse whisper. “But it is alright, mon. Alright?”

Alright.

“Yeah, alright.”

Someone in the room takes the phone, says a hasty “thank you” and Ziggy Marley is gone.

Nic - Jan 24, 2009

respect

Savepost a comment