Graham Reid | | 10 min read

U2: Even Better Than The Real Thing (Perfecto Mix by Paul Oakenfold)

The whisper-voice and marble polish Hilton Hotel in Melbourne isn’t the sort of place you’d normally associate with rock ‘n’ roll. Suits and chic glide by, uniforms open doors and fingerprints on the gilt are removed discreetly by maids with an imperceptible swipe of a cloth. The place breathes class. Upper class.

But this time last week the lobby of the Hilton was a swarm of bomber-jackets, back-stage passes and the well-worn jeans that is rock on the road in the 90s. Because just across the park outside the automatic doors is the MCG. And there, for two nights, the U2 Zooropa travelling show has set up shop.

When rocks comes to town on this scale – a permanent crew of 120, most housed in the Hilton and other scattered in other hotels – then it’s good business.

As some of the crew sit in the lobby bar after the first show and keep those rock ‘n’ roll hours which see last drinks ordered around 2am, the air is full of multinational laughter and voices, stories about that time in Jersey City, talk of the boxes of T-shirts seemingly in permanent limbo between Sydney and Auckland …

And how smoothly this two year tour has been going. By consensus, U2 management is a good employer, knows what its doing and treats its people right.

These guys stay in the Hilton … and the Hilton accommodates rock ‘n’ roll.

But when a classy hotel has three “adult” programmes (sample dialogue: ‘oh baby, that’s right, just like that”), the Pentagon supplies pictures from cameras in smart bombs, and contestants on a game show have to identify fake “new items” from real world (and can’t) then you know you are in the post-modern age where one image is worth about the same as any other.

It’s the television zoo. Zoo TV.

And U2 have brought theirs to town.

With satellite feeds, high-definition screens stacked 20 metres high and technology so far advanced they had to write their own computer programmes, the Zoo TV tour is ambitious, provocative, mind-jarring and maybe even on some kind of as-yet unclear cutting edge.

“I knew it was going to be big, but this was amazing,” wrote reviewer Ian MacFarlane grasping for words in the Weekend Australian after the opening night of the Australian leg in Melbourne.

But there wasn’t much more than that to say. Amazing.

“Television, the drug of the nation …” The Disposable Heroes of Hiphoprisy, 1992

The lights around the MCG go down, 50,000 punters roar in anticipation and on the three-storey-high stage a stack of 50 television screens crackles with high-definition visual static.

More lights on the stage towers flash with blinding intensity, dozens more screens are illuminated. Out of the cathode collisions, sonic mash of Beethoven’s Ode to Joy and blitzkrieg of visuals Bono appears high on the stage engaged in some demented puppet dances before a wall of images.

He does a mocking goose-step and hauls his hand down from a Seig Heil salute which set the political subtext for a show which runs well past the two-hour mark and touches bases with a number of recent periods in the band’s 15-year career.

As white light hits the stage and the rest of the group are lit up, the huge crowd roars again, presses towards the stage and the first brittle chattering notes of Zoo Station are unleashed through the massive sound system.

The band that began life named the Hype and then became the hype – only to walk away from it on their last two albums – have opened in uncompromisingly aggressive mode. Bono takes the mike at centrestage and sneers the lyrics, “I’m ready for the laughing gas, I’m ready ... ready for what’s next …”

But only because he knows where this is going. The crowd is trying to get a hold on it themselves. Ready to let go of the steering wheel, as Bono says?

The screens fire images and words at an almost incomprehensible rate and what can be deciphered is variously funny, ambiguous, oblique or nonsense. Achtung, baby. But achtung to what? Words and pictures fly by.

For an instant it’s as if the languages and images of the world can be brought down to this stage as a crew of over 200 have pulled together high tech, low art, hype and type into a show which can’t be called the future of rock ‘n’ roll for one very simple reason. It’s happening right now.

And only U2 perhaps – 50 million albums sold, a new record deal signed in may for an estimated $400 million for their next six albums – have the financial clout and intellectual curiosity to put it together. The statistics here defy comprehension: 1200 tonnes of equipment, a dozen laser discs preprogrammed, nine cameras scanning the stadium all linked to be mixed live, a sound system that pumps out over a million watts of power, 26 on-stage mikes fed into 60 monitors …

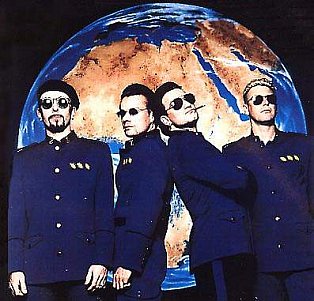

And in the middle of all this are four men from Dublin whose collective worth has already grossed them $1500 million from album sales. Drummer Larry Mullen sits behind a remarkably small kit back and centre, bassist Adam Clayton is off to the right impassively cool behind shades, guitarist The Edge carves out great shards of sound and up front is Bono, outfitted eerily in black leather and wraparound black glasses.

The man who once brought love to town in messianic mode is

now transformed into something like a crack-fuelled cricket as he snarls his

way through Zoo Station, The Fly and Even Better Than The Real Thing …

The last two U2 albums – Achtung

Baby and Zooropa – may not have

done the dollar business like their earlier ones, and radio backed away when it

heard the gritty left-turn U2 had made musically, but on the night as The Edge

drags his Eno-inspired monotone through Numb

and as Bono turns on his Bowie/Lodger

voice for Lemon, the new material

sits seamlessly alongside New Year’s Day and

a mid-set acoustic bracket which includes Angel

of Harlem and When Love Comes to Town.

For a show which has sometimes been written off by English rock writers as the triumph of television over rock, the songs hold their own without difficulty. Where once the band too readily reached for the anthemic, now they take each song on merit. They also include Lou Reed’s Satellite of Love which has Bono singing in a video “duet” with his childhood hero who appears on the digiwall of screens. And they keep stadium gestures to a minimum.

They don’t have to reach out … the screens are doing that for them. And if that makes the Zoo TV show just a little more detached, then that, too, is fitting. This is rock … and television.

Images and words appear and disappear in blink-time and the band call a halt while Bono, as with anyone in these “pass me the remote” days, takes time out to graze the local channels. It’s Ironside briefly, advertisements and, on this night in Melbourne, the Kiwis pasting the Australian openers at the WACA.

The crowd bays, lights race up the huge conning towers that make up the stage and Bono taunts mockingly: “You didn’t come here to watch television, now. Didya?”

The 50,000 roar, “Noooo”. But the answer is, in fact, yes.

Zoo TV may be rock. But it’s also about television.

“Everything you know is a lie. Believe everything. Watch more TV.” Zooropa concert epigrams, 1993

It might be nothing new to note, but it is worth remembering

that the generations which have filled this stadium – and bought the $15

programme and $30 t-shirts – are those which have never known a world without

television.

These are people who watched Live Aid on the small screen and were told it was their Woodstock, have had a decade of MTV and watched the Gulf War and the Koresh compound in flames from the comfort of their own homes. And when they got tired of it, they simply changed channels.

Zoo TV is, in that sense, nothing new. It’s just been brought into a stadium and for two hours people can watch television as they never have before … in the company of thousands of others. It is big, brash and briefly, participatory.

In the ground is a customised Portaloo made over into the

Video Confessional (television camera as priest now, is it?) where people file

in and say what they will. It is all

filmed and towards the end of the concert the best/most

interesting/particularly bizarre are edited out and fired up onto the

videowall. On this night in Melbourne –

the first concert for the band in 10 weeks – the biggest cheer goes to the guy

who intones slowly into the camera: “I’m an undertaker … and I have slept with those who sleep

forever.”

Bono too stalks the stage with his own portable video filming the crowd as words, prerecorded footage and his pictures flash across the screens. This is a concert for the age of video artist Jenny Holzer’s “failed epigrams” (as Time magazine art critic Robert Hughes describes them) which appear on specta-colour boards in Piccadilly Circus, Times Square (right) and San Francisco. It’s music for the age where we send photographs over the telephone and when Sega’s Sonic Hedgehog video game made more money in Britain on the day of its release than the best-selling rock album of 1992, Simply Red’s Stars, did there all year.

And standing before the U2 videowalls are the Donkey Kong kids who have known nothing else. That ... and rock music.

“I do think that we see the platform we have as an opportunity that should not be squandered, one way or the other.” The Edge, last month.

While dislocated images and words assail the eyes it becomes hard to know where to look. The television generations watch the screens but on the long catwalk a belly dancer snakes around tantalizingly while the band plays Mysterious Ways. Bono reaches out … not to her flesh, but to her image on the screen now projected two storeys high at the back of the stage.

Television and reality, they are becoming one and the same. The image? Even better than the real thing?

Then the boundaries blur again. One

is dedicated to the people of Sarajevo who, at the Wembley concert in

September, were given the screens to deliver their own undiluted message of

despair and anger at the world community’s indifference to their

suffering. On this night, however, the

band’s own video appears as they sing it.

It’s a live video now.

Television, in the service of the real thing?

This much imagery can reach overhead fast, however, and the band knows it. The centerpiece of the show, the modestly rendered acoustic bracket at the end of the catwalk, shows the relentless momentum and the fireflashes across the screens are noticeably reduced in the second half of the show.

Older material such as Bullet the Blue Sky and Where the Streets Have No Name are delivered but appreciably free of the self-aggrandising manner of the Lovetown tour. Some of the screens shut down and at the end of Pride with the frozen image of Dr Martin Luther King behind him, Bono abdicates his frontman role again. King can speak for himself in the video age as the footage rolls, there is a palpable frisson of sadness in the crowd.

But did we come here to watch television? Yes and no, simultaneously.

This hemisphere, however, offers fewer video grazing options than Europe, where Bono has scanned the channels. Seeing Australians being whumped at the WACA, however pleasurable for a New Zealander on this night, isn’t the same as the band acting a conduit for the people of Sarajevo.

And when Bono returns as his Macphisto character – decadently devilish – to make his nightly phone call to the famous, there are also fewer options. No Salman Rushdie to phone and then call in from the wings. But Buckingham Palace’s number has been beside the mirrored phone on stage during the day.

He goes for the local option on this night and there on the line is television’s Derryn Hinch, recently sacked from his programme. Hinch, clearly surprised by this call to his home (“How did you get my number?”), responds with gales of laughter when he is offered a job on Zoo TV. The crowd eat it up … then it’s back to the rock.

As the show passes the two-hour mark, the videos ignite again and burning crosses and swastikas are appropriated and condemned. It’s about television and rock … but politics, too.

The back of the handsome programme contains the addresses of Amnesty International, Greenpeace, the Aids Trust and Community Aid Abroad. There is a full-page ad for Zoo Condoms.

Whether there is always a message in the fast-forward language on screen is another matter. But one stands out which may need reinforcing: “Rock ‘n’ roll is entertainment.” And this is never less than spectacular rock ’n’ roll arena entertainment … with a great soundtrack.

“And these are the days when our work has come asunder, And these are the days when we look for something other …” from Lemon on Zooropa, now.

On the last night of 1989 at the final concert of the Lovetown tour, U2 played a concert in Dublin which was broadcast to an audience of over 200 million in a live radio link-up. At that time Bono said, “[Now] we have to go away and dream it all up again.”

They dreamed from live radio to live television.

The Zooropa tour has filled stadiums, the lobby bar and 100

rooms at the Hilton. It sells

merchandising and records and asks more questions that it answers. Mostly, it doesn’t even ask questions,

though. It just is.

It is both using television and about television. What that means is anybody’s guess. But it’s also about rock ‘n’ roll … and rock ‘n ‘ roll as entertainment. At least for the night – short concentration span conceptualism pumped by a backbeat.

What U2 dream up after the final throes of the Zooropa tour, which ends at the Tokyo Dome a week after the Western Springs concert, is anybody’s guess. To look ahead seems unnecessary anyway, even if Zoo TV suggest a path.

But it can’t be called the future … because it’s here already.

post a comment