Graham Reid | | 11 min read

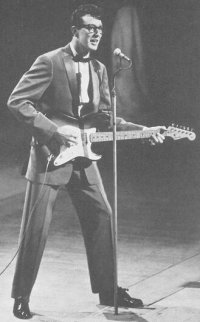

Buddy Holly:Maybe Baby

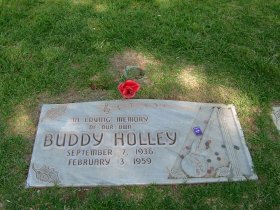

It was 50 years ago, on February 3 1959, that the tail-lights of the red four-seater Beechcraft Bonanza faded into gusty winds over the airport at Mason City in Iowa.

Within minutes the single-engine plane had plummeted into the snow-covered cornfields of the thinly-populated countryside.

And so it was that America woke up on February 4 to the news that Buddy Holly was dead. He was 22 years old and for many, as Don McLean was to sing some 13 years later, it was “the day the music died”.

The teenage John Lennon was bereft. Holly -- with spectacles like he had to wear -- had supplanted Elvis as his hero and with Presley in the army and others sidelined, Holly had been one of the few rock’n’rollers still active.

Holly’s biography is brief, as you would expect. He was born and raised in Lubbock in West Texas; like Elvis he listened to country, pop radio and black music with equal interest; he learned guitar and became the hottest ticket in town.

He saw and met Elvis in ‘54; did radio shows and endless live work; there were some abortive studio sessions in Nashville then he signed to a small label. He pulled together the Crickets and catapulted to stardom on the back of That‘ll Be The Day in May 1957.

He moved to New York and fought with his management; broke up the band, wrote some of his most ambitious songs, married Maria Elena Santiago who took over his management, toured . . . and then the plane crashed.

Not for Buddy Holly the indignity of Vegas Years like Elvis, a slow decline into obscurity like Bill Haley, or life on the oldies circuit with Jerry Lee Lewis and Chuck Berry.

The man might have been gone, but the music did not die.

Buddy Holly was a pioneer of rock’n’roll whose music remains even now fresh and innovative when aligned with that of his peers.

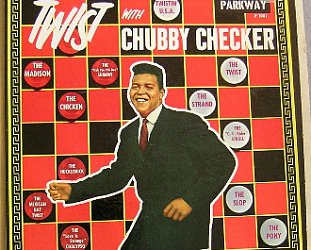

Holly’s songs -- only a couple of dozen recorded in about 18 months -- have been covered by the young Beatles and Stones, Eric Clapton, solo Beatles, Linda Ronstadt, Waylon Jennings (the latter-day Cricket who gave up his seat on that ill-fated flight to the Big Bopper), Los Lobos . . .

Holly has been the subject of three very different biographies; a terrible film starring Gary Busey (which so outraged McCartney he helmed an excellent doco screened by the BBC); and the stage show Buddy which opened in London in the late 80s. It broke box office records in the States, Australia and London. Unlike Holly (who toured as far as Australia), the musical made it to New Zealand where it was equally popular and acclaimed.

To be honest, Holly’s music is of negligible influence today, but they still stand up.

Unlike most 50s rock’n’roll songs which were little more than rowdy slogans -- Shake, Rattle and Roll, Tutti Frutti, Rock Around the Clock and so on -- Holly crafted lyrics which told stories or conveyed emotions, and he could construct a supporting melody. He was a songwriter.

He was also musically curious: for Everyday he used a celeste, an instrument he’d found in the studio but which was rarely heard again in rock until the Beatles‘ middle period.

He experimented with drums patterns and sounds; cribbed riffs but made them his own (Not Fade Away borrowed the “Bo Diddley beat”); used close harmonies country-style (It’s So Easy); dropped barrelhouse piano into Think It Over; and married the urgent beat of Peggy Sue with a distinctive hiccupping vocal.

He worked with his small group, or pulled in a string section for the sublime and simple True Love Ways. He was precociously gifted and even in his small catalogue you can hear extraordinary musical diversity.

His lyrics could be direct and economic (“I’m gonna tell you how it’s gonna be, you’re gonna give your love to me”) or like some Dylanesque haiku (“drunk man, streetcar, foot slip, there you are” on Looking For Someone To Love).

He would lift from varied sources: “that’ll be the day” was John Wayne’s famous line in The Searchers; “maybe baby” was a phrase Holly’s mother used, and those odd lines from Looking For Someone To Love was his uncle’s saying.

Even today the Holly name has resonance: the drum patterns which open Peggy Sue; the movies which have been named for Holly songs such as That’ll Be The Day and Peggy Sue Got Married; the clean simplicity of Rave On or the romantic string-soaked True Love Ways.

As late as the 80s Bob Dylan played Holly songs when rehearsing his bands, remembering perhaps when, as a teenager, he saw Holly play in Duluth. Two nights later Holly was killed.

Holly and his music may not have much influence today but in 1998 -- almost four decades after Holly’s death -- when collecting a Grammy for his Time Out of Mind album Bob Dylan remembered that night in Duluth: “I was three feet away and he looked at me, and I have some kind of feeling that he was -- I don’t know how or why -- with us all the time when we were making this record.”

If, as a complete stranger, Holly could write himself into the biographies of Dylan, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Mick Jagger (the Stones covered Not Fade Away) and Elvis Costello, then we can only imagine what life must be like for Maria Elena for whom True Love Ways was written.

Here was the woman who, for six intense months, lived and worked with the singer as both wife and manager.

Six months may seem a short period in a long life (she is 73 and living in Dallas) but with the music, the legends and more specifically the stage show Buddy, she constantly lived with the legend.

“I never put Buddy away,” she told me in early 93. “I though I’d start a new life and that’s why I remarried, that maybe I could continue with my life. But I was not able to, even to this day.

“And that’s why I’ll never marry again.

“I didn’t do justice to my second husband knowing my feelings were completely for Buddy. I couldn’t stop thinking about him.

“And now being involved with his music again with Buddy, and talking about him, makes it impossible. You can never forget.”

Maria Elena and her second husband divorced and today her three adult children from that marriage are “out and about”.

She was reluctantly drawn on the cost the memory of Holly had on that relationship.

After perfunctory and well-rehearse remarks about how her second husband encouraged her to take an active interest in the musical legacy of Holly, she admits to the price he paid.

“I could never imagine how he felt and how I felt about Buddy. It must have been difficult. Although he didn’t say much about it I can tell it actually had a lot to do with us not being together now. It must be hard when you have to compete with someone like Buddy Holly.

“And it’s not only me . . .. Priscilla [Presley] must have the same thing.

“The people who get involved with someone who has been with a star can always be shadowed by that ghost. But there’s nothing they can do about that.”

Maria Elena may have had only a brief marriage to the Lubbock-born singer but it was cast in true fairytale fashion.

Born Maria Elena Santiago in Puerto Rico, she moved to New York to live with her aunt Provi at age eight after the death of her mother.

Provi was head of Southern Music’s Latin American Division and, after work in various other music companies, Maria Elena joined Southern a few months before she met Holly in June 1958. She was a receptionist and he was a star coming in to discuss a business deal with Southern’s boss Murray Deutch.

Their brief courtship - a morning flirtation, lunch with Holly and the band, and a proposal from Holly after an evening recording session -- has been much documented.

The interracial relationship -- compounded by Holly’s fundamentalist Baptist background and her Catholic upbringing -- found remarkably little opposition within the families, although Buddy’s mother had some reservations, unspecified but perhaps because Maria Elena was four years older than the 21-year old singer.

Some months after their August marriage -- kept secret while Maria Elena travelled as Holly’s “secretary” -- Holly’s father acknowledged the self-confidence the marriage had given his son.

“You’re the best thing that ever happened to Buddy,” he told Maria Elena, according to John J Goldrosen’s thorough biography of Holly. “You’ve cut his umbilical chord. When he was younger he was tied to his mother, then he was tied to [his manager] Norman Petty, but now he’s come into his own -- he’s finally a man.”

But while the Holley family (the original spelling of the name) was happy, producer/manager Petty was not so easily appeased. In fact, there was and is little love lost between Maria Elena and Petty.

While Petty’s astute skills had opened up a national audience for the young singer, his tight control over the musicians -- and most specifically their money, he took co-writing song credits as was the habit of many managers in the period -- became a point of conflict.

Before his death Holly parted ways with Petty, and Maria Elena took over the management role, lining up Holly with top New York photographers for session shoots and using her music industry contacts to advance his career.

As Cricket Joe Mauldin recalled to biographer Goldrosen: “None of us ever saw a nickel of the publishing money. But I saw this beautiful studio and all the nice offices [Petty] had.”

However Maudlin also defended Petty and acknowledged that to paint him as a parasite on Holly’s success would be unfair.

“I have hostilities against Norman, but I think this is only normal with any group that has a manager. At some time in their career they get crossways. I still do feel Norman Petty was very instrumental in our career and success.”

When Holly parted company with Petty, the Crickets remained with their manager/producer, perhaps to lure the singer back to the fold.

It was never to be and it appears Petty’s bad-mouthing of Maria Elena ensured Holly would never return.

“Norman told Buddy that I was a cheap girl who tried to pick up practically every entertainer who walked into the office,” she told Goldrosen in 1974.

Petty -- who died in August 1984 -- had his own view of the break-up between him and Holly and directly, and often, blamed Maria Elena.

“She told him that he didn’t need the Crickets, that he didn’t need me,” he would say.

“He says I was after Buddy’s money,” fired back Maria Elena to Goldrosen. “What money? Norman had it all. Anyway I didn’t need it. I was no poor kid from the slums, I always had plenty. Whenever I needed or wanted anything, my aunt gave me the money for it.”

By the early Nineties however Maria Elena -- who consciously steered Holly away from his Texas background and towards the high-powered New York publishing and business world -- was more circumspect and considered about her responses to Petty.

“Even after his death Buddy never faded away although he never got a lot of promotion from Norman. He never had the management that, say, Elvis Presley had.

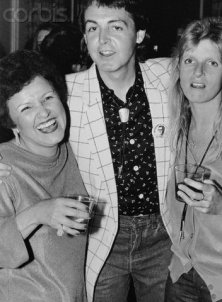

“Norman never worked the catalogue or did the publicity needed. He sold the catalogue to Paul McCartney who started working it so Buddy’s songs are now out there through Paul’s exposure of the music.

“That’s the thing I regret -- that Norman didn’t do justice to the music and let Buddy get out there. He over-protected Buddy.

“But the man is not here now so . . .

“At least he chose someone to sell the catalogue of Buddy’s songs to, someone who loved Buddy and thinks of him as an artist and friend and someone he respected.”

In 1975 Paul McCartney -- who revered Holly as a fresh-faced and impressionable teenager and whose band with Lennon was in part inspired by the name “the Crickets“ -- bought Holly’s publishing and began an annual tribute with Buddy Holly Week. He wasn’t short of stars lining up to play.

Maria Elena has been a guest at some (right, with Paul and Linda McCartney) and takes an active interest in all matters related to the Holly estate. She owns the rights to Buddy’s name, likeness, trademark and other aspects of intellectual property.

She protects these assiduously, and is often unpopular as when she insisted his hometown not use his name in relation to a Walk of Fame in Lubbock.

As with Yoko Ono, she has framed herself as the keeper of the flame and feels chosen.

“We were only married for six months but . . . it was like he was only ever going to be here for a certain amount of time and I had to come into his life for that time.”

She has an office in her home dealing with Buddy business, travels regularly in a promotional capacity, receives awards on behalf of Holly and has been to many openings of the Buddy musical about which she is enthusiastic.

It was when the production opened in London in 1989 that she first became aware of the musical biography in which she, naturally, appears. A newspaper tracked her down in Texas and flew her to England to see the show.

“I was pleasantly surprised because you are always apprehensive about these things and you can’t judge the response they will get. You always have to ask if they are true to life.

“I had mixed emotions because of all the memories they bring but I thought it was very good. The movie [The Buddy Holly Story in 1978 which starred Gary Busey] was also good, although there were some things that weren’t true to life.”

There is a story that she left the theatre during a screening because she couldn’t bear to watch the lives being acted out.

“I am always reluctant about these things but it was my children who said I was being egotistical and should approve of them to let the world hear this wonderful music again.”

There is a moment in the show which catches her every time she says, when the actor playing Holly sits down with the woman who plays her and, in a mock-up of the New York apartment they briefly shared, sings the simple, affecting ballad True Love ways that Holly wrote for her.

“That is always my favourite moment because that is exactly how it was. He came in and said he had this song he had written for me and wanted me to hear. He sat there and played it on his guitar just like he does in the show.”

As her language blurs the boundaries between the long gone reality and the recreation for an audience,. Maria Elena Holly lets her much publicised, prepared responses go for a moment.

“You know, deep inside he was my first love . . . . And that, you never forget.”

Which, in some way, might also explain why after that fateful flight into the history books he wasn't forgotten by Lennon, McCartney, Jagger, Clapton . . . .

post a comment