Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Nick Cave: I Had A Dream, Joe

"I went out walking the other day the wind hung wet around my neck my head it rung with screams and groans from the night I spent among her bones... "

- Opening lines on Nick Cave’s album Henry’s Dream.

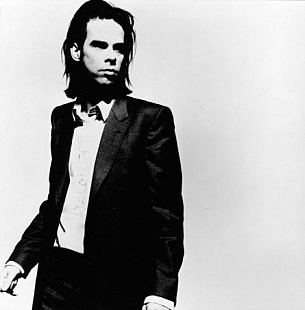

If rock music has a reigning Lizard King, it’s Nick Cave. Painfully thin, black hair swept back from a severe widow’s peak, shrouded in a permanent halo of gloom and cigarette smoke, Cave scowls into the vortex between Robert Johnson’s terrifying blues, Kurt Weill and a barn-dance in some in-bred Appalachian valley. The tunesmith from the charnel house, he makes music of almost criminal intent.

Cave’s songs walk through ghostly wind-whipped woods or swim in the shallows of despair beneath the killing moon. “Sorrow’s child wades in deeper [and] invites you under,” he sang on his previous album, The Good Son. And he means it, maaan.

In black suit and with bony fingers clutching a microphone, Cave, has been the vulture wheeling over bleak torch songs where fag ends of guilt and death smoulder. He feeds on sex and anxiety.

He’s also the one who lets critics get off their best lines and pull out a few fifth-form horror clichés. He’s an opportunity to take out the Edgar Allan Poe, Southern gothic novels or create a few dark demons from a middle-class childhood which never actually offered the throat-rattle confusion of landscapes of fear Cave deals in. He is wonderful...but he’s also functional.

“Cave is an empty vessel into which you can place whatever you want,” wrote Andrew Smith in a particularly astute live review in Melody Maker six months ago.

And Cave himself, although increasingly weary of his public persona as the Ambrose Bierce of rock, helps to feed the myth. Recently he noted that The Good Son was thematically and lyrically “still chained to the same bowl of vomit” as he always surveyed.

There are other Nick Cave realities, however, even if his latest album, the grisly, hypnotic Henry’s Dream doesn’t climb far from the bowl. Henry’s Dream is more grim, obsessive Cave music...but there’s a different Cave man now.

The heroin-soaked days are gone (“I didn’t really want to kick drugs, I had problems with being busted and basically it was either give up or prison”) and parenthood has changed him subtly too. Two years living in the splendid Brazilian isolation of the splendid surroundings of Sao Paulo have also made a difference. A quieter life. He wears a Rolex now.

Earlier this year a filled-out and less reptilian Cave turned up at his record company in Melbourne and wasn’t recognised.

An empty vessel?

“Yeah? Who wrote that?” he says with a suspicious laugh from his home in Sao Paulo.

“Well...people see me in various different ways and some have obviously got completely the wrong idea. It’s not in my interests to get bogged down in the that stuff.”

Cave, sounding weary and wary, spends considerable time explaining why he doesn’t like doing interviews much. But he is candid, humorous and genuinely apologetic for missing this phone call the previous day. “Sorry, I forgot and went out,” he says sheepishly. But...

“I find the more I discuss my work, the more removed I become from it. For that reason alone I hate doing interviews. I’ve done so many for Henry’s Dream that I’m starting to find the whole thought of that record nauseating. I don’t think there’s a question that anyone could ask that I haven’t answered.

“The record disgusts me, because when you have abstract feelings towards a thing in the first place you have to make them concrete. That doesn’t become your true feeling but just what you say in interviews.

“By having to have an opinion which you externalise and consolidate, you end up having wrong notions.”

He talks with frustration about interviewers who want to bat around the old cleaned-up-junkie-hero idea and others who want to test out their polysyllables and half baked literary theories on him. It’s tedious.

And to work the same vein, albeit one which is stimulating and demanding for himself and his audience, means there is little new to say even about a work as elemental, melodic an engrossing as Henry’s Dream, recorded, as always, with the Bad Seeds.

“I look at writers and musicians whose work I find inspiring and they have a lifetime pushing away at one idea....Like Samuel Beckett or Leonard Cohen. Basically, I’d like to continue in that way.”

Continuing has been what Nick Cave has done best. His first band, Boys Next Door mutated into the Birthday Party, the band that for much of the 80s allowed Cave’s peculiar vision grounded in anguish and grinding rock to swim upstream against most other trains of thought. Cave was the outsider, a boundary rider for whatever new apocalypse he thought up.

Like some figure from Coleridege' Ancient Mariner, this son of an Anglican minister would grasp whoever he could with skinny arm and fevered imagination, then tell for the nightmares. It was no surprise when the Melbourne-born band quit London for Berlin, a cry altogether more fitting for Cave’s smack-and-syringe storytelling.

He formed the Bad Seeds, watched friends die, wrote some of the most exciting, and scarifying music ever committed to record, assisted on the script for the Ghosts of the Civil Dead movie, wrote his acclaimed, almost impenetrable and little-read novel And the Ass Saw the Angel and appeared as himself in Wim Wenders’ film Wings of desire, a role which led to writing for Wenders’ recent and spectacularly over-wrought Until the End of the World.

Two years of living in Brazil has meant he hasn’t had a chance to see this latest Wenders – or do much other than drink beer and read. He speaks little Portuguese and, despite all those years in Berlin, very little German. He’s wilfully the outsider but appreciates the collective nature of film work.

“I really enjoy being part of some larger project,” he says with something close to enthusiasm. “It’s refreshing being involved with a lot of people, especially if you have to put your trust in people you don’t know.

‘You take a risk if you act or are even slightly precious about the way you want to be perceived. I don’t consider myself an actor. Any director who uses me risks me doing a shallow version of character.”

Yet the ever-vigilant Cave was also prepared to take the risk himself with Henry’s Dream, the first album he has recorded since Boys Next Door days which has involved a producer, in this case David Briggs, who has worked regularly with Neil Young.

Not my idea, he says grimly. The record company insisted and “some of our worst fears were realised.” After the critical acclaim for The Good Son three years before, that kind of pressure was inevitable, although Cave insists, rightly, that the new album certainly wasn’t tailored for chart success. And understandably it enjoyed very little - if any.

Briggs pushed them to do very tight, energetic takes he says and that was fine, “but when it came to the mixing, he never understood how the band should sound, so we had to take that way from him and remix the whole thing in Australia.”

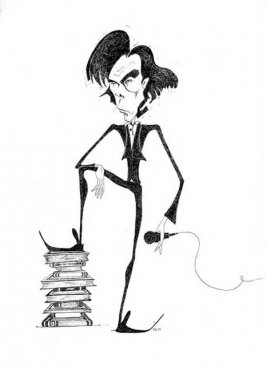

Back to the land of his birth and a place he now says he’d like to spend more time after being a self-imposed exile for a decade. He’s had enough of Sao Paulo and of the frustrations of distance meant the album cover art was beyond his control. It’s almost a caricature of himself, he says.

But then Nick Cave has increasingly become a caricature. His work has the same sinew and edgy presence it always had – Henry’s dream, which tosses the ball back to the band in a visceral, acoustic way, is even better – but Cave can barely escape his past. He speaks now of “his career’ and how it “can’t be managed properly” from Sao Paulo.

He’s thinking of going back to London, but he now has to pack for a family and moving isn’t as easy as it once was he says ruefully. The pure boredom in Brazil has led him to write more (“the piano used to be my greatest enemy”) and has the broad outline from a new novel. But yeah, he’s moving out some time soon.

Wherever Nick Cave ends up, it probably won’t change his music much. Same bowl of vomit, same obsessions, same hyena circling rock music's corpse. For years he strived to become himself and the image became the man. Now, at 35, he writhes quietly to escape. The questions are always the same, the replies are in the music.

It’s chilling music but, as he illustrated when talking to the Sydney Morning Herald recently, he still gives good quote. Asked where he sees himself in the rock’n’roll pantheon, he replied: “As a kind of novelty act. The ageing geek in a circus, covered with feathers, with chicken blood running down my chin.”

Being Nick Cave dies hard with him. He offers the caricature in lines like that. It ensure s that, whatever Nick Cave the man might be, Nick Cave will always be – in the minds of those who care passionately about this disturbing visions – the vulture wheeling, the haunted bluesman swimming in despair and staring into the vortex.

The one obsessive worship – and critics get to use their best lines on.

post a comment