Graham Reid | | 4 min read

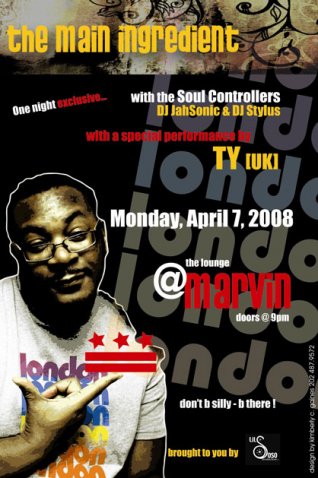

From this distance, British hip-hop comes down to a few big names: the Streets, Dizzee Rascal and Skinnyman. It takes keen interest -- or a look at the nominees for the highly regarded Mercury Prize -- to come across rapper Ty.

But he's not a new name. His debut album Awkward appeared three years ago in 2001 and the Mercury-nominated Upwards came out in 2003. He's had a run of successful and catchy singles (including Wait a Minute and Oh U Want More?, featuring Roots Manuva) and his fusion of soul and jazz into hip-hop has set him apart.

He was born in London to a Nigerian family and lately has connected with drummer Tony Allen, who shot to fame with the Lagos rebel Fela Anikulapo Kuti.

It adds up to a rapper with a broad and intelligent view of his art, and a consciousness that this is an art which can elevate the soul as much as possess an edge from the streets which gave it birth.

"I have 10 godchildren, so people have assigned some responsibility to me for 10 young people," he says. "Not all rappers get that. I'm so much more aware that when kids are around and you let them swear, then later you have the worry of something you haven't checked coming back to bite you.

"Rap's been blown up into these clowns with gold chains and hi-top haircuts. But the reason we make music is for the feeling -- there may not be a message. Rather than being caught up in being called a conscious rapper or whatever I've just tried to make music. So if I make a song which doesn't perpetuate a cliche then that's what I will do.

"The [gangsta] way is easy but not realistic, not for me. Where I live and what I see is a constant reminder that you have to be realistic in how you deal with people. You can't drive a flash car in a poor neighbourhood and park it outside and expect nothing to happen."

Ty, real name Benedict Chijioke, says that when he was growing up in London he was just like other kids tuned to the pop of the day: "Duran Duran, the Thompson Twins, Fine Young Cannibals, soul like Marvin Gaye, and the BeeGees and disco songs."

The first hip-hop track that affected him was Doug E. Fresh's The Show: "It wasn't the first I heard but was the one that really stood out. There's that keyboard horn at the beginning. It was quite anthemic and almost like a fanfare of horns that crept up on me."

He started rapping in his bedroom then to people on the street and says hip-hop had him studying it like he'd never studied anything before.

"I knew the words to most of the songs and I was fascinated by the music behind them and it got to the stage where I got to perform to a classroom. Then I was performing in my area in the youth centres. You don't have confidence, you learn to front. Hip-hop is about looking like you have more confidence than you actually do."

The biggest problem that rap and hip-hop faces in Britain is that powerful media don't let it come into the mainstream, he says.

There is always the suggestion that British rap is struggling, but that isn't the case -- it's doing fine. But trying taking it out of the hip-hop community and you come against a wall.

"If there is any genre not allowed to be on television, not play-listed or given the same push as pop, it is hip-hop.

"We're pop artists ready to become mainstream but we're not given the same platform.

"My record is one of the easiest albums to become commercial as far as being a credible rap record and having the ability to transfer into a bigger market.

"But we found doors closing to us.

"Specialist people in jazz, soul and hip-hop picked up on it but there was a bottleneck regarding particular shows which would have allowed to go mainstream. I don't have a theory on it."

Let's put one forward, then. Racism?

"I wouldn't be surprised. I can't say there isn't racism in the music situation -- but some of it is just ignorance and they are not interested in making this music open and big for a young audience."

If anyone could progress the music it is Ty, whose use of live musicians, and connecting with his Nigerian roots, gives his sound breadth. He observes that the Streets, Ms Dynamite and many record labels conspicuously keep the label "UK hip-hop" away from themselves because it puts off important people.

Working with Tony Allen was a turning point and made Ty realise that the revolutionary activist and musician Fela Kuti hasn't had the same sort of kudos that Bob Marley and James Brown had.

"But they were all equally powerful in their own way.

"When you check his stance, Fela was by far the fiercest of those three so maybe that's why. My parents were playing Fela music and it was their kind of hip-hop in their day."

The discussion turns to gun culture in Britain and Ty questions why so many young men had to die while governments did nothing. Are young black males expendable?

But while he thinks deeply about such issues and drops them into his lyrics, he denies carrying a flag for any particular cause. If others change because of what he brings up, the responsibility he advocates, or decide to use real musicians like him, then his job is done.

"But I won't make a big noise. You won't see me leading a parade with a big band and a fanfare."

As Bob Marley said: "Check my life if I am in doubt"?

"It is as simple as that."

post a comment