Graham Reid | | 10 min read

It’s an old line but no less true for all that...and when you put it to Vernon Reid of Living Colour, he knows exactly what it means: “Everyone sees the world from their own disadvantage point.”

It’s late at night in New York City and Reid is at home and obviously tired. But he still gets a laugh out of the quip. He knows what it means because he sees it all the time...notably from rock critics.

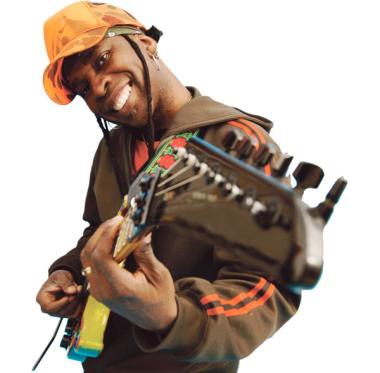

As a 15-year veteran of the music business – starting in left-field jazz outfits, moving through hard-edge funk bands and now a seven-year mainstay of Living Colour – Reid has seen the hype, the lies, the profit motive and the hidden agendas.

He’s smart, articulate – and frustrated by some of it. If it wasn’t about the core pleasure of making music, you suspect he wouldn’t be doing this stuff at all. As one of Living Colour, rock’s pre-eminent black band, he’s been carrying the weight and confronting critical perceptions within the analysis of rock.

As a founder member of the influential Black Rock Coalition back in late ’85 – with Village Voice writer and author Greg Tate – he has articulated what he has seen happen as the white critical establishment and power-brokers have crafted revisionist versions of rock ‘n’ roll history. From their own disadvantage point – wilfully or by uncritical unconscious consensus – critics have promoted their own agenda and relegated black artists.

As rock‘n’roll increasingly fell into the hands of the white, liberal academics – blame Rolling Stone and the late-60s “alternative press,” if you will – the black contribution was sublimated or ignored. Yet rock ‘n’ roll came from the blues, counts among its progenitors the likes of Fats Domino, Little Richard and Chuck Berry, then leaped ahead through Jimi and Sly and into the Parliament/Funkadelic combine.

Even today, rock still feels the aftershocks of James Brown, Otis Redding, the wicked Pickett and – increasingly, if the careers of Shai, Boyz II Men and Bel Biv Devoe are anything to go by – a hundred doo-wop groups.

“There’s a whole hidden history in rock‘n’roll,” says Reid, warming to the subject despite his tiredness and no doubt a hundred other rehearsals of the argument. “Bands like Mandrill, War and Osibisa exist now in a kind of no man’s land. Bands like MC5 and the New York Dolls, obscure as they were, are championed by white critics.

“I was privileged to see the Velvet Underground reunion recently – now there is a band whose reputation has been held by the white rock‘n’roll critical Establishment. I think they’re a great band, I really do. But you can’t deny part of the reason they are still viable enough to even make a comeback is because they are part of that hierarchy.

“Now, I see the Isley Brothers – a great band who had rock‘n’roll hits – but I wonder if they’ll ever be accorded their due.”

As he has always been, Reid is scrupulous about saying his beef with critics is not personal, more an observation about the very critical criteria in operation in rock. A critic like the late Lester Bangs, he notes, is rare: “He may have hated Living Colour, I don’t know...but no one wrote about [reggae artist] Big Youth like he did. He had the true spirit of the music.”

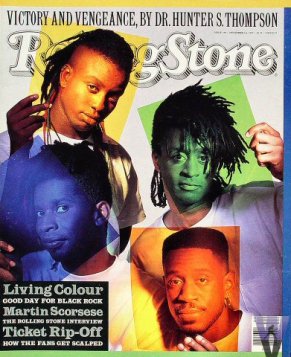

Reid’s observations are particularly relevant however when considering the Living Colour career trajectory. Signed to Epic Records in ’87 after being rejected by all other companies, their debut album, Vivid, was a slow starter but eventually sold two million copies. It also met with critical acclaim with many writers enthusiastically, but misguidedly, noting the arrival of the first all-black rock band.

But the reception for Time’s Up of ’89 was more muted. Critics seemed confused by what Living Colour were about as the band threw free-jazz and juju guitars at their heavy material. What was clear was that the white rock critical Establishment was working from a very different disadvantage point.

These days, white hard-rock bands find their references in other white rock bands. Sebastian Bach of Skid Row, for example is on record saying he’d love tell you he listens to all those old blues guys like Robert Johnson ... but he doesn’t. He listens to Guns N’ Roses and AC/DC, bands two, if not three, generations removed from the black sources of rock. That’s fine ... but it makes white rock self-referential.

Consider by contrast the tapes Living Colour were taking on the tour bus back in 1990: avant-jazz pianist Cecil Taylor’s In Florescence, the Afro-pop of Ray Lena’s Nangadeef, De La Soul’s Three Feet High and Rising, Fishbone, Public Enemy, Bonnie Raitt, albums from Peter Gabriel’s Real World label and King’s X’s heavy Gretchen Goes to Nebraska.

That’s a whole world of music shoved into the Walkman ... little wonder some white rock critics working from narrower references found the diversity of Time’s Up too unsettling and, in their opinion, unfocused.

“It’s weird,” says Reid, “because when people like you, they like you to keep doing what they liked about you. With Time’s Up, it became, ‘What are they trying to do?’ for the critics. They felt they had some kind of overview but it’s very presumptuous to think you know what’s in the head of an artist.

“Some said Solace of You [on Time’s Up] was us taking from Paul Simon’s Graceland. But hey, wait a minute! I’d been listening to [West African guitarist] King Sunny Ade and [Zairean] Rochereau and all those different musicians independently and on my own - believe it or not – so I felt some of that influence.

“And then I’m told I’m trying to be like Paul Simon! The critical mentality there is saying to me, ‘You couldn’t have been listening to African music.’ I’m saying this without rancour...but the rock critical Establishment is predominantly white and male. That’s not to say they are card-carrying racists, but there is a certain way of hearing things and having them cross-referenced which is interesting to me.”

That Reid should feel some anger about this is understandable. After all, he worked with strongly African-influenced jazz artists such as Jamaaladeen Tacuma and Ronald Shannon Jackson years before he formed Living Colour.

But as Living Colour vocalist Corey Glover cynically noted recently: “People know their history as far as two weeks ago. As we all know, history is disposable, everything about your culture in this world – and in one ear and out the other.”

His point is a good one. In June, for example, the English rock mag Vox did a countback on political rock ... MC5 got a couple of mentions in this survey which went all the way back – way, way back to ’77.

History in rock is starting to look like it began the year you first noticed it. Naturally Curtis Mayfield, Isaac Hayes and Stevie Wonder didn’t rate a mention. As for the Last Poets, Gil Scott-Heron and Sly? Forget them...

For Living Colour and their recent Stain album, it’s almost as if the novelty of an all-black rock band has worn off. Although not quite the fully realised stunner that Time’s Up was, Stain is musically and lyrically strong enough to command attention. But Stateside, where the reviews were more favourable than those for Time’s Up, the album peaked at only 26 on the Billboard charts, then dropped quickly despite heavy touring by the band to promote it.

Reid says he is disappointed by sales, “but everything is supposed to be big these days and it’s become like, if you aren’t big, you are nowhere...”

“I don’t think like that and even when the band was ‘big’ I never felt ‘big.’ That’s become the way music and art is defined, but not every album will be as ‘big’ as The Joshua Tree.

“Records are phenomenological events and so many factors come into play...but we’re doing okay.”

Being a darker album – “it’s more the internal demons we’re dealing with,” said Glover recently – Stain doubtless met some consumer resistance ... but there is also the larger perception that rap is on the cutting edge of black music and rock is an regressive idiom. Significantly, the Living Colour audience is predominantly white in America, and in Europe the band is operating at the same level as Alice in Chains, says Reid, offering the white rock reference point.

Over the years Living Colour have dealt with the way the media creates icons (Cult of Personality), the right-wing attacks on immigrants in Germany (Auslander) and Ignorance Is Bliss. It’s a broader, more intelligent and better-articulated platform than most bands offer, but Reid is uncomfortable with the jocular suggestion that, in a world of heavy metal, death metal and “metal metal” (as coined recently by Karl Wallinger), they could be construed as “message metal.”

“Hmmm, no that’s not what we are about. You take Axl Rose singing, “Turn around, bitch I got a use for you/besides you got nothing better to do and I’m bored” and he’s called a rock‘n’roll rudeboy. That’s a message. But if I comment on that and say it’s exploitive and fucked up, I run the risk of being considered some goody two-shoes.

“It seems it’s not cool in rock‘n’roll to have a basic sense of decency. It’s like you have to cover it up with a heroin habit or some outrageous public display of wild behaviour. People fucked up on dope are considered the most cool in rock.”

This is the perspective advanced by jazz musician Wynton Marsalis also: the media are more comfortable dealing with the stereotype of the black artist – broke, doped and down‘n’out – than taking on the educated, poised, assured face of many black musicians today. It’s a simple piece of positioning; gangsta rappers make better stories than Berklee School of Music graduates.

“The rock‘n’roll rap has always been, ‘Be different, be crazy, break all the rules.’ The worst part of rock'n’roll is that it is promoted as the place where everyone can be free – whereas nothing could be further from the truth. It’s all rules and regulations and creating another hierarchy like all other hierarchies. It has become very ritualised ... but the great bands – like King Crimson and Richard Thompson - transcend that.

“Maybe rock‘n’roll should just be adolescent fantasies. But that denies its history and connection with the blues.”

What Living Colour and more particularly the Black Rock Coalition have been about is denying the stereotypes which exist within rock. The frustration Reid has always felt is that once the drawbridge went down to let Living Colour through it went back up just as quickly on other black bands. Bad Brains, anyone?

Glover recently noted how many young black bands were being compared – unfavourably – with Living Colour. It denies those bands the opportunity to be themselves. Just as white bands and critics reference themselves off others, the critical cabal insists on making comparisons between bands as different as the Michael Hill Bluesband (whose references are more aligned to Gil Scott-Heron and Brian Jackson), the Afroblues jazz poetry of Blue Print and the power trio Shock Council.

It has been one of the Black Rock Coalition’s stated missions to break the stranglehold of stereotypes and misconceptions which surround what critics think black rock should be, rather than dealing with what it is.

What Living Colour are calling for when they say “time’s up” is the end to the stereotyping/pigeon-holing/media analysis/promotion-relegation on black artists. And, “by any means necessary,” it’s now time to say it’s not Malcolm X over Martin Luther King, or Living Colour over Michael Hill ... all can coexist. After all, Skid Row, Guns N’ Roses, Metallica and all those other white-boy marketable commodities (c’mon down, Rolling Stone/Cream/NME/Melody Maker mediaphiles), occupy the same territory without being mutually exclusive.

“You know, the Black Rock Coalition got together as just a bunch of friends,” says Reid, “but I have to ask myself that, if black musicians didn’t get together and ask questions, would anybody have said anything? You can talk about separatism and all that, but what is the real question here?”

The question is the word that dare not speak its name. Racism.

From where Vernon Reid stands, rock is the black-born music that gave him the thrill of hearing Sly and the Family Stone’s Family Affair, Led Zeppelin’s Black Dog and the Beatles’ Lucy in the Sky with Diamond. It gave him a chance to be free of himself on stage. to live outside that person who thinks too much, and pull together a consciousness of black rock history that stretches across the water from West Africa juju guitar to the Funkadelic throw-down and reggae rocksteady.

And in the seven-year lifespan of Living Colour it has also given him the opportunity of giving something back. Something hard, fast and heavy, to be sure ... but also something driven by a conscience, heart and a perspective that is rare in rock today.

But that’s only if you aren’t seeing it from your own disadvantage point.

For more on this subject in jazz see Amiri Baraka at Elsewhere.

DateMonthYear - Apr 14, 2009

This whole article is maybe more relevant now than when originally written. the revisionist view of 'rock' history has become more prevalent, and black artists in particular are being presented in ever more narrowly defined stereotypes.

SaveChris - Apr 14, 2009

The whole subject of revisionism in musical criticism is very interesting... in particular i can't stand the Marsalis brothers/Ken Burns version of Jazz history; that jazz died in the seventies only to be resurrected by the neo-conservative 'Young Lions' in the 80's... did a lot of damage then and to this day.

Savepost a comment