Graham Reid | | 2 min read

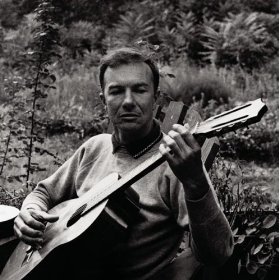

Pete Seeger: Hallelujah, I'm a Bum

When I was growing up and the sound of the Beatles and the Stones was the soundtrack to my life, the folk movement out of the US just seemed quaint and grounded in another era.

While artists such as Joan Baez and the young Bob Dylan made an impact, a bunch of buttoned-down college boys in sweaters singing "hang down your head Tom Dooley" or women in chunky-knits whining "we shall overcome" just seemed limp and lame.

They still do of course, which is why that Chrisopher Guest movie A Might Wind was so funny.

As time went however and I learned about Woody Guthrie and the Wobblies, the McCarthy witch hunt and so on, that folk movement looked and sounded less and less limp, and rather more courageous than I had given it credit for. I have to say though, Pete Seeger still wasn't on my radar and knowing that he tried to cut the cable on Dylan's electric and electrifying appeance at the 65 Newport Folk Festival just made him seem like a silly old duffer.

Seeger insists he wanted to stop Dylan, not be cause he objected to electric guitars, but because the sound was so bad.

Maybe, maybe not.

Seeger -- who has sometimes been called "the conscience of America" -- had a remarkable life and the resurrection of interest in him during this past decade, prompted by Bruce Springsteen championing his music, was arguably long overdue.

Seeger, who died this week at 94 showed few signs of slowing down in his final years -- he sang Guthrie's This Land is Your Land at Obama's first inauguration with Springsteen.

His was a remarkable life of dissent, consistency, music and protest.

Born to a musical family in New York, he dropped out of Harvard just before World War II and began a life of musical itinerancy and liberal political activism. He wrote and documented America's story -- its people, complaints, weaknesses and strengths -- in song, and made more enemies than he had hits.

That said, his music was influential (his group the Weavers inspired a whole movement of copyists) and his appearances at fund'n'conscience raisiers were often powerful and pointed lightning rods for dissent.

His time as a member of the Commnist Party inevitably drew him into conflict with the prevailing mood of America after the war and although he had served his country, he was a target for the House Un-American Activities Committee.

His statement to them was as direct as any of his lyrics: "I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this."

Needless to say he also opposed America's involvement in Vietnam and other such conflicts, and had been an active environmentalist from long before it was fashionable.

All the time he was singing, recording and influencing new generations, most notably that around Greenwich Village in the early and mid Sixties, among whose number was Dylan. He went to Russia in '65 which only confirmed in the minds of many that he was a threat to national security.

Quite how one man with a banjo or guitar could be so may seem odd, but his was a powerful voice and his songs had currency and the ability to travel.

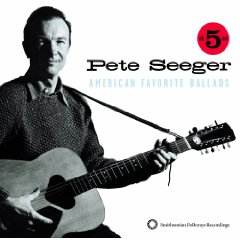

The five CD collection of his Smithsonian Folkways recordings -- which cover ballads recorded between 1957 and '62 -- form a cornestone of his work in that they reach out to the heartland in songs aimed at children and adults singing them together, but they also cover a wide range of themes (railroads, Native Americans, cowboys, old time religion, gunfighter songs, folk-blues and more).

Listening through to these songs you can hear the pulse of an older and perhaps less cynical America, a nation that Seeger felt was betraying its potential and better nature.

His life was never easy but, like the wheat that bends in the breeze, he let the vagaries of politics and presidents blow over him and come back to still stand tall.

A life less ordinary.

post a comment