Graham Reid | | 5 min read

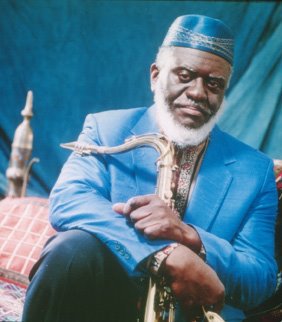

Pharoah Sanders (with Bill Laswell and Foday Musa Suso: Kumba (1995)

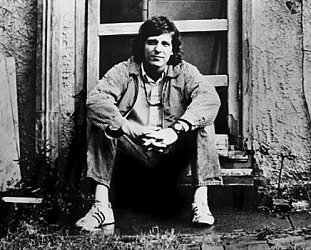

Pharoah Sanders proves to be not the easiest of interview subjects. But if he has a poor phone manner and doesn't sound interested in talking, you tend to forgive him because he's a jazz genius. Or at least an occasional genius, although one who has consistently alienated critics.

Maybe because he has rushed in and is about to rush out we should be grateful for the 15 allotted minutes -- even though they are torturous, and punctuated by silences and ambivalent or non-committal answers. Still, he didn't even bother with the two interviews set up for Australian journalists.

Sanders is 63 and on his way to New Zealand with a group which includes his longtime pianist William Henderson. Asked whether he plays much these days -- a web search turns up very few gigs -- he offers the unhelpful, "Somewhat, uh-huh."

On subsequent probing he says that while he now lives in Los Angeles he's "just passing through".

"I don't deal with the musicians around here too much. My whole thing is still in New York City and when I want to use guys I go back East. I'm just an East Coast person, I just live here that's all."

So are you playing much back there?

"Somewhat. In and out maybe once or twice a year. Once is enough."

Suggest to him that his albums in the 90s with hip New York producer Bill Laswell caught a new generation and he seems baffled. "New generation?"

Yes, younger listeners.

"Oh, I see what you mean. Well, maybe."

At this point you may wonder why anyone would continue interviewing. But it is Sanders' body of work -- from the mid-Sixties when he was with John Coltrane, to the late Nineties when he worked with Laswell and the Gnawa musicians of Morocco -- that you keep in mind when repeating questions and getting little response.

Sanders' playing demands respect, and a blazing set I saw in New York's Village Vanguard five years ago is enough to make me hang in despite increasing frustration.

In the 60s Sanders was considered the most fierce tenor saxophonist of his generation. He developed a tone which blasted like a blow torch, was influenced by the free jazz of Albert Ayler, and came to the attention of the great Coltrane, who saw him play in New York clubs in the mid-Sixties.

Sanders -- born Farrell Sanders, he adopted the uniquely spelled Pharoah -- had come to New York after a childhood in Little Rock, Arkansas, where both his parents were music teachers. He played blues gigs around his hometown and after high school went to Oakland Junior College in San Francisco, where he became known as "Little Rock".

He hooked into bebop and according to most sources played with saxophonist Dewey Redman.

"I never played with him too much," he barks. "Interviews get wrong things. I knew him closely, we'd sit on jam sessions together in San Francisco, but that's the only time."

At 20 Sanders moved to New York, yet despite his unquestioned talent he was often unable to get gigs. He'd pawn his saxophone, work whatever jobs he could and sometimes slept in the subway. When he did play it was with the likes of musical innovators Sun Ra and Don Cherry.

He recorded a fiercely intense album for the ESP label in 64 which was "terrorist grunge with a shake of mysticism" according to one source, and "composed entirely of extremes: overblowing, screaming out clusters of notes, the line a furious supersonic scribbling" according to another.

Jazz lore has it that saxophones would shriek for minutes after he stopped playing.

He'd formed his own group in '63 which included pianist John Hicks (with whom he would play occasionally over the following three decades), drummer Billy Higgins (of Ornette Coleman's famous Fifties free jazz ensemble) and bassist Wilbur Ware. It was this group saxophonist Coltrane saw at the Village Gate, and in late '64 he asked Sanders to sit in with his band.

Sanders played regularly with Coltrane, and although he was never made an official band member he appeared on most of Coltrane's most demanding albums up to Coltrane's death in '67.

At the time, Coltrane was on the crest of his spiritual quest and the music stretched out, single tunes reaching past the 30-minute mark. Critics were often underwhelmed and dismissive of Sanders' part in the dialogue between the two saxophones. They acknowledged his physical and emotional power but felt it was undisciplined.

Sanders offered raggedly scribbled outbursts in contrast with Coltrane's iron-prowed obsession, said one writer.

Sanders has always seemed bemused by those wanting to probe his relationship with Coltrane. He has consistently said they could sit together and simply not converse. The conversations took place on the bandstand.

"We just played music that's all. It's very simple. Just played music. What was there to talk about? Talk about what?" he asks rhetorically.

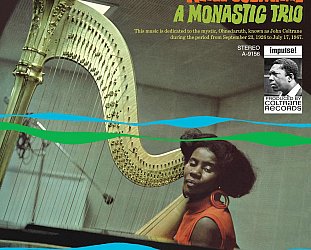

After Coltrane's death, Sanders was rootless. In the late Sixties he joined pianist Alice Coltrane - John's widow - for her Indo-jazz fusion and spiritually inclined music which has largely been reduced to a footnote in jazz histories, yet the album line-ups included great players like tenor saxophonist Joe Henderson, bassist Ron Carter and drummers Jack de Johnette and Rashid Ali.

"I don't know, I can't speak for her," Sanders says when asked to consider her legacy. "I haven't seen her in quite a number of years."

The Seventies didn't favour Sanders: he regurgitated earlier material, tried disco, then didn't play that often. When he returned to jazz his tone was more mellow and palatable. In the Eighties and Nineties he was on small labels and explored West African music in a jazz context. Some said his music was flabbier and more dull.

When he recorded an album of jazz standards critics who had previously described him as too tough now said he was too soft.

"I don't worry about who writes stuff like that," he laughs. "I don't have nothin' to do with them and I have no respect for them anyway. I don't listen to stuff like that, it doesn't bother me one bit. It don't bother me. I just go and play and play for people who want to hear my music."

And despite his infrequent live appearances there are many who do want to hear his music. His song The Creator Has a Master Plan is a jazz standard, and his synthesis of jazz and African idioms pulls big crowds at places such as the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival.

Now an elder statesman of jazz -- with a distinctive, jaw-line white beard -- he has no advice for younger musicians.

"Younger musicians have been through it all and it's up to them to decide what they want to do with their music at this point. They've been through all the schools."

He says he loves to travel and explore all kinds of music, as he did in West Africa and Morocco, and shows unexpected enthusiasm for didgeridoo. He says he would like to work with an Aboriginal player when he's down this way.

But last year Sanders said he wasn't a jazz musician, didn't have anything to do with that word and wasn't interested in being a jazz musician.

"Maybe what I do is not jazz, I don't know. If they say that [it isn't] then do they want to leave or stay? I don't mind. I just try to play music, you know?"

ANDY - Sep 21, 2021

I didn't realise he was naturally grumpy! When I met him backstage in the early 2000s he was certainly grouchy, but I thought that was because he saw I had a rice paddy hat for him to sign and all the band members were laughing and waiting for his reaction...

SaveIt was a rare honour to see him and briefly bother him.. I didn't stick around for a proper chat as that was never my style unless it was an actual interview:)

post a comment