Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Smokey Robinson and the Mirales: I'll Try Something New

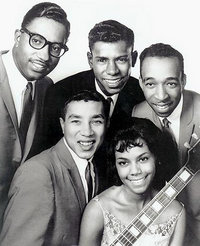

It was one of those fortunate circumstances that Motown Records founder Berry Gordy from Detroit met his label’s star (and later his producer and boardroom exec) Smokey Robinson -- who had been around the Detroit scene in high school groups for years -- when both of them happened to be in New York.

The ambitious Gordy, who’d written a couple of songs and got into small-time production, was in New York checking out the competition. Robinson and the Miracles had all but given up on getting a deal back in Detroit so had headed to the brighter lights trying to sell themselves and their songs to a publisher.

Their encounter changed their lives, and the direction of popular music.

But, ironically, their first minor hit together -- the doo-wop Got A Job -- didn’t appear on Gordy’s famous Motown label. That company was still some years in the future and Gordy leased it to End Records, and the romantic soul-drenched ballad Bad Girl to Chess. And the group’s first huge hit Shop Around came out on Gordy’s Tamla label, a forerunner to Motown.

But the story of Smokey Robinson and the Miracles -- told on the handsome 35th Anniversary Collection, a four-disc Motown box set released in ‘94 -- is essentially the story of Motown.

It was Smokey who fashioned the Temptations' career by writing and/or producing hit after hit for them, and he turned Mary Wells into the most famous black woman pop singer of the Fifties with a series of minor hits then giving her an international breakthrough with My Guy in ‘64.

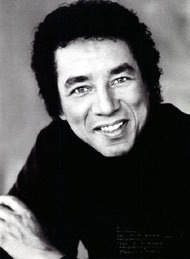

Robinson -- apparently called Smokey because of his light skin -- defined Motown’s Sixties style in his superbly crafted songs and exceptional voice: it says enough that artists as diverse as Bob Marley, Bob Dylan and the Beatles were all early fans.

And it’s a measure of his particular genius that so few of the songs he recorded with the Miracles were taken on by others. Smokey’s versions were so . . . so definitive.

The few who did cover his songs (outside of the Motown roster) did so by way of homage: the Beatles covered You Really Got A Hold On Me on With the Beatles; there was the Stones somewhat ill-considered Going to a Go-Go . . .

But these people never claimed to take the songs as their own.

How could they? Robinson’s rich, pure and high voice was -- even later on material from his worthy solo albums such as Cruisin’ in ‘79 and Being With You from 1980, included among the six post-Miracles tracks in the box set -- and is, peerless.

Robinson had a high, sweet and expressive voice: he’d grown up on his sister’s Sarah Vaughan collection and it was seeing Clyde McPhatter, who also sang high, which convinced him it was possible for a man to sing like a woman.

Robinson’s songs wrote themselves into the autobiographies of two generations; those who got them the first time around, and their kids who got them on soundtracks two and three decades later.

And consider how it all started, with their answer song to the Silhouettes’ Get A Job.

Well, Smokey Got A Job -- and it was turning out hits: Shop Around (included on the box set in both the slow Detroit and then the more urgent re-recording that Berry, right, insisted on and which became a national hit); I’ll Try Something New; You Really Got A Hold On Me; Mickey’s Monkey; Tracks of My Tears; I Second That Emotion; Tears of a Clown . . .

And he gave away My Girl to the Temptations. Everyone speaks of his generosity in the studio, as a songwriter and as a man.

Smokey loved words and his lyrics worked on paradox, antithesis, wordplay and spinning a cliché: “I don’t like you . . but I love you”; Bad Girl was an early twist on “bad” meaning “good”; and song titles include What’s So Good About Goodbye, The Day You Take One (You Have To Take The Other), I Gotta Dance To Keep From Crying, My Business Your Pleasure, The Love I Saw In You Was A Mirage, I Second That Emotion . .

And he created his own mythology: this astonishingly suave and good looking man following up Tracks of My Tears with Tears of a Clown (which was recorded within weeks of Tracks but not released for four years -- when it became a hit).

He might have loved wordplay like some Brill Building day-jobbing songwriter, but he was also older, married and had a maturity that was evident in his sometime autobiographical material.

After he and his wife Claudette (a member of the Miracles) suffered the premature birth and death of twin girls Smokey turned his pain into an aching declaration on More Love. “This is no fiction, this is no act. This is real, it’s a fact. I’ll always belong only to you, each day I’ll be living to make sure I’m giving more love and more joy than neither age or time could ever destroy . .”

This was a very long way from the innocent doo-wop he started out on. But looking through even those early songs his lyrics ached with emotional pain and yearning.

Robinson -- after grooming a successor -- quit the Miracles in ‘72 and although he had an occasional solo career (punctuated by massive hits such as Cruisin’ in ‘79 and Being With You in ‘81) he largely concentrated on his role as vice-president in the Motown hit-machine until he resigned in ‘88.

He continues to release albums but mostly spends his days picking up awards.

His music resonated down the generations and as late ’76 George Harrison would write Pure Smokey for his Thirty Three and A Third album, and of course there is a character in the Dreamgirls play and movie (which he hated) based on him.

In 2009 on the 50th anniversary of Motown, Smokey was being spoken about, and revered, again.

It was a long time ago when someone asked Bob Dylan who America’s greatest living poet was, no doubt expecting him to name Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti or some hipster Beat.

Maybe he wasn’t being so much glib as honest when he answered.

No prize for guessing who he named.

post a comment