Graham Reid | | 3 min read

Chet Baker: The Thrill is Gone

Trumpeter Chet Baker's death in 1988 was tragic -- but, at 59, he was lucky to have lived so long.

A brilliant stylist whose work in Gerry Mulligan's piano-less quartet in the early Fifties -- and whose recordings in Paris shortly afterwards -- are worth serious investigation, Baker modelled himself on Miles Davis at his most ineffably cool.

Although his trumpet playing rarely explored much beyond a diffident mid-range, Baker was an accomplished and distinctive stylist.

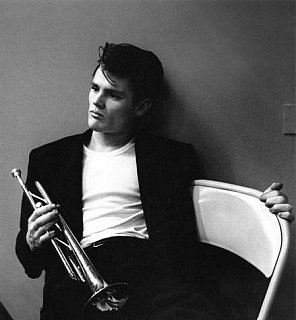

He was also a beautiful boy. With high cheek bones and moody good looks, and as a singer whose smoky style breathed seduction, he was James Dean recast as a Sinatra-styled crooner. If he'd been born in the Seventies, he'd have been in Calvin Klein ads.

He looked jazz as much as he played it.

Reviled by many jazz writers who were dismissive of his singing and drew the inevitable comparisons between this West Coast trumpeter and the more innovative Davis of the East Coast, Baker's life was also plagued by demons of his own making.

It is said he learned to play the trumpet in a fortnight, and that his singing came equally effortlessly. Perhaps because of the ease of his accomplishments he became a spendthrift of his talents and didn't respect them. He certainly didn't respect himself and developed a smack habit of heroic proportions. He was given so many blessings that he didn't have to try for anything, not women or fame which so many of his young peers courted.

Baker's life had all the elements of a terrific James Dean live-fast-die-young story. Except he lived.

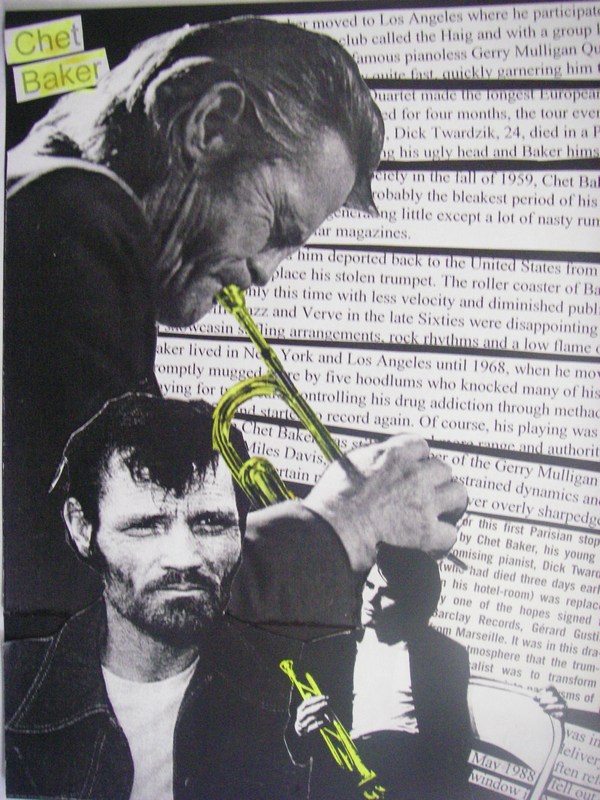

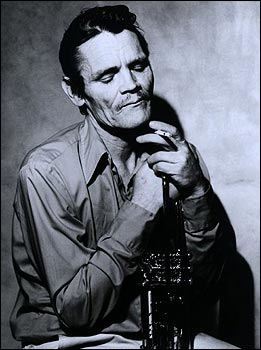

He lived to do time, lose his teeth during a beating in the mid-Sixties and have to learn to play trumpet all over again, to look in the mirror and see his youthful beauty eroded by his habit, to hear his music float away from him into an ether of diffidence . . .

Then in May '88, he fell to his death from a hotel room in Amsterdam.

He'd been sitting on the window ledge and his manager said, "he probably nodded off". Chet was great one for being on the nod, and of course heroin and cocaine were found in his room, and his system. It was the final fall in a life which seemed to have had an endless downward trajectory.

Baker's style and image undergoes periodic revivals: in New Zealand Greg Johnson modelled himself on Baker during the first few years of his own trumpet playing/singing career in the late Eighties/early Nineties, and Elvis Costello wrote Almost Blue in the manner of Baker's atmospheric jazz-noir stye -- and then had the trumpeter play on Shipbuilding.

Baker's style and image undergoes periodic revivals: in New Zealand Greg Johnson modelled himself on Baker during the first few years of his own trumpet playing/singing career in the late Eighties/early Nineties, and Elvis Costello wrote Almost Blue in the manner of Baker's atmospheric jazz-noir stye -- and then had the trumpeter play on Shipbuilding.

Almost Blue became one of Baker's signature tunes, the other being My Funny Valentine. (In the film The Band's Visit there is running mention of Baker and that song as a seduction piece.)

Bruce Weber's homo-erotic documentary Let's Get Lost in '89 put the ferociously photogenic young Baker back on the screen for a new, hip young audience, attracted as much -- you suspect -- by the heroin chic as the jazz Baker played.

By the early Nineties the young German trumpeter Til Bronner was effectively resurrecting aspects of Baker's style -- the wispy muted trumpet, the unadorned singing style -- and he was playing material associated with Baker such as My Funny Valentine. He also paid tribute in the lyrics of his own piece Have You Met Chet?

Baker's legacy in jazz is as thin as his voice was in the later years, but he did leave a large body of work for others to explore, even if it was a very narrow vein: the cheap films he made in Italy where he did walk-on parts for dope money, all those marvellous photos of him as a young man, even those of him as a drug-ravaged walking corpse in his 50s.

But there was one final irony in this life so wasted, and "wasted".

Despite the imprisonment, being kicked out of various countries, having the learn how to play wearing dentures, and all the rest of the attendant problems he brought on himself, Baker just kept doing it.

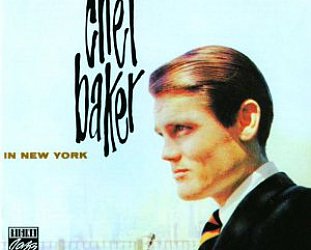

He recorded dozens of albums in the last decade of his life, and some have argued that his album Chet Baker in Tokyo recorded in his final year counts among his best work.

By that time he may have been a ghost of himself and had worn the gifts he was given smooth and into a series of crowd-pleasing gestures, but he was also occasionally still finding something within himself.

There is a perfect description of Baker's playing in Geoff Dyer's book But Beautiful: it also summed up the man as much as the music.

"Chet put nothing of himself into his music and that's what lent his playing its pathos. The music he played felt abandoned by him.

"He played the old ballads and standards with a long series of caresses that lead nowhere and subsided into nothing."

mark robinson - Jun 15, 2009

Wonderful musician. I was lucky enough to see Chet at Ronnie Scotts. i was a member of the club for several years in the 80s and early 90s. Mark

Savepost a comment