Graham Reid | | 2 min read

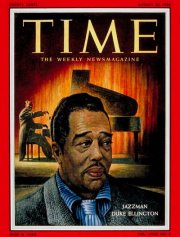

Duke Ellington: Blues for New Orleans (from New Orleans Suite, 1970)

Few statements about music can be delivered unequivocally, but here's one: Edward Kennedy Ellington was one of the greatest composers of last century. And of all time.

And no discussion need be entered into.

Other than to observe he didn't "compose" in the traditional sense: most of his best-known songs were written with collaborators, his instrument was an orchestra, and his gift was as part of a collective.

His genius was perhaps more akin to that of a movie direcotr than a painter or an individual jazz genius like Charlie Parker.

Given all that, Duke Ellington (1899-74) could only have found his expression in jazz.

Writer and critic Leonard Feather used to argue that jazz was the classical music of the 20th century because in it you could hear the diversity and dissonance of a century in turmoil, and also something of the human condition.

Ellington was of jazz, but bigger than it. He wrote elaborate suites which reached thematically from the Middle East to Latin America, complex music for orchestra, liturgical music, blues and pop standards.

Not all were successful -- there's a strong argument his forte was the four-minute miniature, and that the extended works don't hold up -- but it is impossible to imagine a world without Sophisticated Lady, It Don't Mean A Thing If It Ain't Got That Swing, Black and Tan Fantasy and dozens of others.

Even if he didn't "write" them, they are Duke's.

James Lincoln Collier's 1987 biography of Ellington outlined the argument against acceptance of Ellington into the pantheon of great composers: he relied heavily on Billy Strayhorn for arrangements and musical advice; he was a good but not a brilliant pianist; he lacked musical knowledge and the self-disciple to acquire it; and, because he wrote at rehearsals and took ideas from the musicians as they improvised around his often-unformed ideas, one observed, "I don't consider you a composer, you are a compiler."

But it was precisely because of the jazz milieu, the collective art, that he could find his expression there.

He wrote for specific musicians and their tone, intuitively knew how to place tonal colour in harmony or counterpoint, and managed to find (although Collier and others say more by accident than astuteness) those who could embellish, improvise and give character to what he wrote or heard inside his head.

It is a measure of the flexibility of Ellington's music that it could be played by large and small ensembles, and that New Orleans gris-gris and voodoo-pop man Dr John could also play Ellington on his album Duke Elegant in 2000.

That album found the good Dr on excellent form and reconfiguring Ellington tunes into distinctive, funky New Orleans grooves.

Ellington's work can, and has been, orchestrated and jazz-rocked, soul-funked and distilled to its essence for solo guitar. It is both a template and a finished tapestry.

Narrow minds unthinkingly impose a hierarchy on the musical arts. You know the kind of thing: opera at the top, jazz around the middle rungs below string quartets and orchestral music, and rock music -- with a few honourable exceptions such as the Beatles -- at the primordial depths.

Ellington gives the lie to such nonsense. He was, quite simply, a great American composer who worked in a serious, co-operative art form.

You can analyse his music, re-interpret it or simply whistle it.

More than a quarter century after his death, people still are.

As Dr John says in the liner notes to Duke Elegant: "You want to know the ticket to immortality, write a bunch of tunes that people can keep on singin' and playin'."

Duke Ellington did.

post a comment