Graham Reid | | 10 min read

The Beatles: Come Together

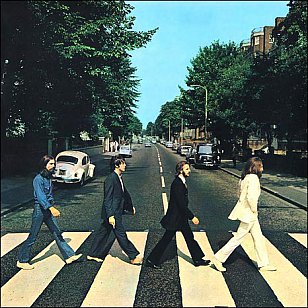

Four decades ago the Beatles released Abbey Road, the album that marked the end of their career even though the inferior Let It Be would appear later, a sad coda to decade which they defined.

Producer George Martin loved Abbey Road and considered it “Sgt Pepper, Mark II . . . it was innovatory but in a controlled way, unlike The Beatles and Let It Be which were a little beyond control”.

John Lennon on the other hand would later dismiss it, and he was especially damning of the segue of song fragments on the second side -- Martin’s idea -- which created a memorable mini-suite.

Lennon had wanted all his songs on one side and McCartney’s on the other. (He didn't say where he thought Harrison's might fit.)

Although most of the sessions had run smoothly (at least according to Martin and McCartney’s memory), others report tensions and especially a huge argument which came to fisticuffs between Lennon and Harrison.

Yet Abbey Road sounds like the fine full-stop on their career and includes some of the best music Lennon, McCartney and Harrison ever wrote. Harrison’s Something (which McCartney said was the best thing on the album and Frank Sinatra acclaimed as his “favourite Lennon-McCartney song“) proved the Quiet One to be a mature songwriter.

And the cover of Abbey Road wrote itself into history as one of the Beatles most iconic.

On the street outside EMI studios on August 8, 1969, while a helpful policeman held up traffic in the leafy suburb of St John’s Wood and a photographer stood on a ladder in the middle of the road, the Beatles walked back and forth across the pedestrian crossing having their picture taken.

It took just 10 minutes and for the rest of the day the individual Beatles went their separate ways: Lennon and McCartney back to Paul's place, Harrison off to London Zoo with roadie Mal Evans, and Ringo Starr went shopping -- before they met up at the studio later to continue work on what would be their final sessions together as a group.

In the course of their lives together as a band, that photograph seemed a mundane incident. But one of the six photographs Iain Macmillan took that day became the cover for an album simply named after the street outside EMI Studios.

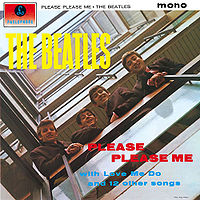

And in a curious piece of symmetry to a career that unwound gradually in personal vindictiveness rather than ended abruptly, that casually shot cover echoed that of their debut album Please Please Me (recorded in one day, February 11 1963) of just six and half years previous.

For that cover the band -- which had a couple of hits but, as with all British pop groups of the time, wasn’t expected to last -- were hustled up to a stairwell in the EMI offices and Angus McBean took a quick snap of them looking down at the camera.

Few today mimic or pay homage to the Please Please Me cover, yet on any given day scores of people cross Abbey Road and have their photograph taken “just like the Beatles“.

Long before you reach the most famous recording studio in the world you can hear the sound. But it is not music coming from inside the walls.

It is the squeal of tyres as another car or truck slams on its brakes because a tourist -- and often a whole group -- has stepped onto the nearby pedestrian crossing to have a photo taken in imitation of that iconic image.

And it isn’t just tourists too young to have been born when the album came out in September 1969, or sixtysomething Beatles fans reliving a fading memory. Margaret Thatcher and U2 have also strode purposefully across the street outside the graffiti-ed walls of the studio, now renamed Abbey Road Studio, for publicity purposes.

The Red Hot Chili Peppers notoriously walked across the zebra crossing naked but for well-placed socks for their Abbey Road EP released in 1988. The Simpson were here too -- and the cover has inspired more homages, copies and parodies than any other in rock.

The famous cover might have been harder to copy had the band gone through with a briefly mooted idea of calling the album Everest (after a brand of cigarettes engineer Geoff Emerick smoked) and headed off to the Himalayas for a photo shoot.

But these were the closing overs of the Beatles’ extraordinary career and, with perhaps the exception of McCartney who was a constant cheerleader, no one could be bothered.

So out onto that crossing they went while Macmillan took a few quick snaps, one of which McCartney later chose for the cover.

Oddly enough this photograph, ordinary in the extreme and which had taken just minutes of precious Beatle time, soon became the centre of an amusing controversy.

In the late Sixties a Detroit radio host Russ Gibb spread a “Paul is dead” rumour and suggested McCartney had been killed in a car accident in 1966 and was replaced by a stand-in. He used song lyrics (“he blew his mind out in a car” from the Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album) and album cover art to support his argument (The Beatles standing around a grave on the cover of Sgt Pepper’s, in another cover shot McCartney with his back to the camera).

And Abbey Road? It was obvious to the conspiracy theorists: Lennon in white was a preacher or religious figure; George Harrison in cheap denim was the grave-digger and Ringo Starr in a dark morning suit was the undertaker. McCartney was wearing a suit but had taken his shoes off (“it was a nice hot day“ he explained later) and apparently in Sicily a Mafia body is laid out in bare feet.

In the background was a Volkswagen “beetle“, the number plate of which read “28IF”, a discreet reference to the fact McCartney would have been 28 if he had lived. (In fact he would have been 27, but no matter.)

People back then took the Beatles and their music very seriously indeed, sometimes to the point of absurdity.

By the time of Abbey Road --and their different attire may have been emblematic of this -- the Beatles were no longer the coherent group they had been when innocent Beatlemania swept them to global fame in 1964.

They were older, had partners and other interests, Lennon was itching to get out, Harrison was weary of the whole circus, and they'd even toyed with the idea of a cover for the Get Back/Let It Be sessions-cum-album which parodied Please Please Me (right) but highlighted the changes.

As individuals they had changed rapidly, just as the Abbey Road studios in which they recorded had during those few but fast years.

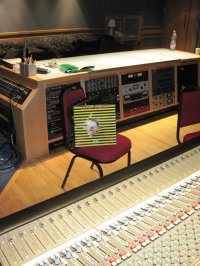

When the Beatles first entered the EMI studios, inside a 19th century building, in June 1962 to record Love Me Do and three other songs in a two hour audition-cum-session, the studio was locked in an earlier era: there was a uniformed doorman, the engineers wore white lab coats, sessions ran strictly to union rules when it came to observing tea breaks, and there was small canteen where you get a nice cuppa.

The studio equipment was primitive by today’s standards: the Beatles recorded on 4-track and for most of their career Beatles’ albums were mixed for mono release. It was only as an afterthought that they were processed into stereo.

By their final years, when they retired from touring in August ‘66 and became a studio band, the scene inside the studios had changed: they kept their own hours and sometimes block-booked two or three of the studios at a time. The mood was more casual, and beared, long-hair engineers looked like rock stars rather than high school science teachers of the Fifties.

It was a similarly sunny day as that of the album cover when I crossed over for my first appointment in the building. A dozen young Japanese were already lined up while a patient lorry driver waited until they were all photographed and across.

Nearby a tour bus waited, ready to disgorge its cargo of temporary pedestrians.

My guide was an engineer/producer Alex Marcou who took me through the two main studios then down for a cup of tea in the cafeteria.

The EMI Studios building at Abbey Road may be synonymous with the Beatles, but its story began long before the Sixties. The original nine-bedroom house -- with five reception rooms, two servants‘ rooms, a wine cellar and a huge garden -- was built in the 1830s and passed through many hands before it was sold to the Gramophone Company Ltd in 1929.

The EMI Studios building at Abbey Road may be synonymous with the Beatles, but its story began long before the Sixties. The original nine-bedroom house -- with five reception rooms, two servants‘ rooms, a wine cellar and a huge garden -- was built in the 1830s and passed through many hands before it was sold to the Gramophone Company Ltd in 1929.

It opened as EMI Studios in November 1931 with Sir Edward Elgar conducting the London Symphony Orchestra through Land of Hope and Glory while George Bernard Shaw sat in the audience.

In the years before the Beatles arrived a rollcall of genius climbed the five steps to the modest doorway: Yehudi Meuhin, Sir Thomas Beecham, Sir Adrian Boult, violinist Jascha Heifetz, cellist Pablo Casals . . .

Fats Waller and Gracie Field recorded here, so did Paul Robeson, Al Bowlly and Vera Lynn.

Glenn Miller and his orchestra were here in September 1944. A few weeks later their plane disappeared on a trip to France. Music from their final sessions wasn't released until 50 years later when copyright lapsed.

Then there were the Goons, and Peter Sellers with Sophia Loren recording their novelty hit Goodness Gracious Me, and in the pop era Cliff Richard and the Shadows, Adam Faith, Frank Ifield and many more.

In the late Thirties Winston Churchill had visited and said he thought he'd come to the wrong place, "it looks like a hospital".

It would be three decades and the Beatles odd work schedule before the place loosened up.

On my amble around -- through where the Hollies, Pink Floyd and Ella Fitzgerald had also walked -- Alex gave a running commentary and said if I wanted to come back I could stay in one of the two penthouse apartments which had been added. He mistook me for someone much more wealthy.

Over tea and sandwiches I had to admit that while I expected to get some thrill out of being in the same rooms where so many songs that had shaped my life had been recorded I hadn't really felt much at all.

He sympathised, it was studio after all and really only made sense when musicians were working there.

And then Alex -- from the most famous studio in the world -- asked what his prospects would be like in New Zealand: he was sick of the London traffic.

I broke it to him gently.

Abbey Road Studio would be unrecognisable to the likes of Sir Edward Elgar. Today the studio boasts 72-track mixing desks, expanded studio spaces including a penthouse suite, a restaurant and bar, the private garden . . . and a live web cam showing the pedestrian traffic on that famous zebra crossing outside.

On December 3 2009, 3 Abbey Road will celebrate 90 years since it was converted from suburban home into a recording studio, arguably the most famous studio in the world thanks to four men who not only made their music there but also chose, one bright day, to have their photo taken outside it.

And then name the subsequent album in its honour.

As producer Mickie Most observed, “Abbey Road has remained part of the tradition of the record business and one of the best albums ever made was called Abbey Road. And you can’t get a better advertisement than that”.

****

CODA: In mid 2009 I went back to Abbey Road to listen to the Beatles remasters in advance of their release. I have written about that experience at Elsewhere under The Beatles Remastered and The Beatles After the Remasters.

But on a personal note, and for the record, two other things came into play.

The night before I left New Zealand for six weeks in Europe, the first day of which was to be at Abbey Road for the playbacks, I went to a hospital in Auckland to be briefly with man whose music, art, film, life and attitude I respect immensely. More than he could ever know.

Chris Knox had suffered a stoke and in those few moments together I asked him -- the most knowledgable and yes, obssessive -- Beatles fan I know, if he had ever been into Abbey Road.

Chris shook his head, and I said then I would get him there.

My small gesture was to take one of his album covers with me and prop it up in the studio so Chris could listen to the remasters on that rare day. Chris was there with me.

Also, my son AB -- with whom Megan and I were staying -- was allowed to bluff his way into Abbey Road that morning and together we sat in that special, almost most holy, of places and listened to the music that I, then he, had grown up with.

A special time in both of our lives -- and I want to thank here the following who made it happen: Chris Caddick and Thierry Pannetier, both formerly of EMI NZ; Rae Foster of EMI NZ.

A special time in both of our lives -- and I want to thank here the following who made it happen: Chris Caddick and Thierry Pannetier, both formerly of EMI NZ; Rae Foster of EMI NZ.

And Paul Bromby at EMI UK who was a gentleman and recognised that having my son and Chris there was very important to me.

I think his understanding was a reflection of how this music, commercialised or otherwise, had imprinted itself on people's lives.

Paul Rowe - Sep 7, 2009

Hi Graham, you don't need another comment from me, but thanks for another great article. This month is going to be a great one for Beatles nuts, with all sorts of perspectives, new & old being published (The Times article by Ray Connoly is good if you haven't seen it yet).

Save(very envious of you being allowed into the hallowed rooms, but as you say, perhaps it's for the best...)

post a comment