Graham Reid | | 11 min read

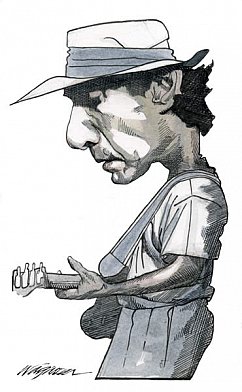

Ry Cooder and Ali Farka Tour: Bonde (from the album Talking Timbuktu, 1994)

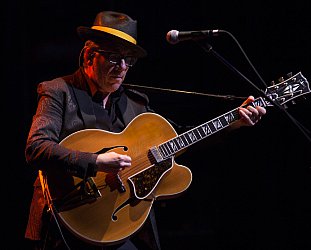

Ry Cooder -- if a slightly flinty 15 minute conversation with someone who rarely gives interviews suggests -- gives the clear impression of someone who doesn’t like to waste his time. His answers can sound abrupt, he barely laughs even when he makes a mild joke, and bristles at some questions.

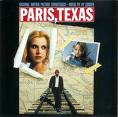

The other problem in talking with Cooder is simply this: at 62 he has such a long career that you barely know where to start. He played with Captain Beefheart and was guest guitarist playing slide on the Stones’ Let It Bleed and Sticky Fingers in the late Sixties/early Seventies; he recorded a series of much admired solo albums in the Seventies which explored regional American musics (Hawaiian, Tex-Mex, gospel) as well as blues and jazz; and spent most of the Eighties recording soundtracks, among them the haunting music for Paris, Texas and Walter Hill’s Western The Long Riders.

He has recorded with Mali guitarist Ali Farka Toure and Cuban Manuel Galban, worked with John Lee Hooker, Mavis Staples and most famously perhaps with the Buena Vista Social Club which he pulled together.

He recently released an expansive double CD retrospective The UFO Has Landed but it could have happily been a five CD box set.

So rather than dig back in these byways -- because he gives the impression of a man who moves on quickly -- it might be better to ask him about what he is doing now and hope that we can work towards these other things, as well as his most recent ambitious trilogy of conceptual albums which have explored the Hispanic music of East LA (Chavez Ravine in 05); Depression-era America (My Name is Buddy, 07) and the car culture of the 50s (I, Flathead, 08).

But right now, other than being on tour with Nick Lowe . . .?

You know Paddy Moloney and the Chieftains? He’s working on a record and he’s asked me to help -- but otherwise I’ve just got to make sure my amps are working right and I’ve got the right shirt and right shoes for this tour.

You seem to be constantly busy but I am sure do take time out. When you do, do you still practice every day?

I spend a good part of the day playing the instruments, several different one. It’s necessary because you can’t play if you don’t play, especially when you get older you’re gonna lose the facility and ability to range around on the thing if you don’t keep doing it.

I spend a good part of the day playing the instruments, several different one. It’s necessary because you can’t play if you don’t play, especially when you get older you’re gonna lose the facility and ability to range around on the thing if you don’t keep doing it.

Plus I like to do it, it’s comforting and soothes my troubled mind so to speak.

We are all aging however, do you notice any attrition of your faculties when it comes to playing?

No, in actual fact I’m a far better player now, my coordination is better than it ever was which can the case with musicians. Probably not horn players, trumpets are tougher on you -- although Louis Armstrong sounded good although even he had to taper off at a certain point. It has something to do with musculature in the face.

But for the instrument that I play, and the piano for instance, as long as you stay on it and don’t have any other health problems you are going to get better. It stands to reason, you have more understanding and comprehension and more ability to coax these interesting sounds from the thing.

I think I’m getting better, so the aging thing doesn’t bother me in that regard. There are other things which seem annoying, eyesight is one. But not on the instruments.

We were just in Europe and we were paying really good, I was improvising and it sounded nice and I was feeling fine.

Delighted to hear it. You’ll forgive me I don’t actually know where to start with your long career but I find it curious, given that you are an active musician, that people have frequently described you as ‘a musicologist’.

That’s just idiocy to me. That’s so facile and just tossed away by people who just don’t understand. Real musicologists are scholars who study and understand certain things academically, and they do the research and they know what they know.

But musicians don’t approach things that way, you approach it from the ability to intuit things, that’s what playing an instrument is. You might be old like Jascha Heifetz [who played classical violin into his 80s] or some Russian pianist, but it always comes from your ability to produce a tone, it’s a tone production thing and you try to make a beautiful sound and that takes all kinds of things intuitively.

Some people have the intellectual ability to grasp Beethoven which I could never do. But we musicians do this out of feeling and some kind of quest and that has got nothing to do with scholarship and study. So actually when people say that about me they are totally wrong.

I appreciate the notion, they want to feel I‘m a guy who knows things. But I don’t know anything, I just make it all up. It’s just some kind of crazy fantasy world for me, that’s what it has always been.

On the other hand if you stay aware you’ll learn things and that helps you gain a kind of resonance in the things you do.

It’s not good to just sit there and twang because you’ll reach a limit. But if you learn about other people and other experiences then you can broaden your horizons.

You seem to have always followed your instincts and worked with many different people, but latterly the musical challenge of the California trilogy saw you unearthing important areas of American culture as much as music. That seemed such a long view and took place over a longer period of time than your previous work.

No, that’s the thing I’m saying, I can’t work that way. I usually stumble on something. This business of Chavez Ravine was always there, right there. I was looking at Don Normark’s photographs [of LA in the 40s] one day and I thought, ‘man, I know [Mexican-American singers] Lalo Guerrero and Don Tosti were still alive but not for very long so I thought I might as well get to it.

This East LA music is one of the greatest things and so unique I just thought, ’Let’s get to it. If you wait another second these cats are going to evaporate and there ain’t no more‘.

And it was true. I made the record, worked on it for three years, and both of them died during the process. If you wanted to put your hands down on a sound or musical concept that is peculiar to Los Angeles you have to have the people who did it. You can’t have as a fan, that’s what I am. I like things, but it doesn’t mean I can represent these people they have to be there. The old people are gone in 60 seconds and I‘ve been knowing this all my life. My greatest mistakes were always made when I got lazy and didn’t try hard enough and someone was lost. 2009 is rough on twangers is what I‘m sayin‘ Everybody is dying: Jim Dickinson, Mike Seeger fer chrissake.

And it was true. I made the record, worked on it for three years, and both of them died during the process. If you wanted to put your hands down on a sound or musical concept that is peculiar to Los Angeles you have to have the people who did it. You can’t have as a fan, that’s what I am. I like things, but it doesn’t mean I can represent these people they have to be there. The old people are gone in 60 seconds and I‘ve been knowing this all my life. My greatest mistakes were always made when I got lazy and didn’t try hard enough and someone was lost. 2009 is rough on twangers is what I‘m sayin‘ Everybody is dying: Jim Dickinson, Mike Seeger fer chrissake.

It comes up fast and this knowledge is lost and that person’s not there to take your call or chat a bit or learn something from.

I just had a long e-mail correspondence with Mike about banjos while I was in Europe and then he stopped e-mailing and thought, ’I wonder what’s wrong?’ and then I got back and got the news.

So what are you going to do?

You better make your hay while the sun shines. That’s what I’m trying to do, get something done, bring the word out. And have a nice little time.

You seem to have done a lot of one-off projects with people such as Ali Farka Toure and [Indian slide guitarist] VH Bhatt. Do things like that just stop naturally or do you like to just move on?

It appears to you this way but it’s like this: [record producer and boss of World Circuit] Nick Gold called and said, ’Do you want to record with Ali Farka Toure, do you know who he is?’ and I said, ’Yeah I do -- but who are you?’

He said he owned a record company in London and so forth. I said, ’You want me to play with Ali, but does he want to play with me?’ because of course I would play with him any time.

Then the phone rang one time and a friend said there’s this guy who plays weird Indian slide guitar and I said, ’I don’t know anything about Indian music, it’s crazy. It’s too long and it’s too hard. I can’t do it’. But be he convinced me.

So I went over there to see Bhatt.

But sometimes these things are like stops along the way because you are moving along your path. You meet somebody but the path stays the same.

I can’t play Indian music to save my life and I can’t play African music very easily either.

But the good thing about records is they bring people together and you have an experience. For instance you are in a studio. Me and Bhatt were there two hours, me and Ali were there three days. Barely.

But in that time if you can conjure up something then you can say, ’At least we have a record and we moved towards something from his side and my side and then we moved on‘.

That’s what musicians do habitually. The fact is there are things in your life you continue to do and you pursue. But me and Bhatt were there hardly three hours. But he was obviously a virtuoso cat and had the raga thing down and the lore and the musicology down, what the hell am I going to do?

In retrospect you were extremely lucky with the whole Buena Vista project because it came about by pure accident when the musicians from Mali didn’t turn up, right?

Yeah. Total accident. I have a good fix on that because Nick Gold had an idea to bring West African Malian guitarists to join the guys in Cuba, which I thought was a bit unlikely. I didn’t know what those guys could do together.

But when we got down there and the Africans couldn‘t make it we said, ’Let’s just get all the cats we can find’ -- because we knew the names, because in Cuba you always know the names because there aren’t that many who are living.

So we got a room together and once you’ve done that you think of all the classic records which have been made in this particular room or place, and some of these people have been involved. So it was, ’What are we going to do?’

One of the simplest ways is to just put everybody together and see if they relate and can come up with something, since they weren’t normally going to be found playing with one another.

For instance [singer] Compay Segundo and [pianist] Ruben Gonzalez never would have recorded together because in Cuba they have these distinctions. But me coming from Santa Monica, you don’t make them and you learn not to.

You can say, ‘Okay, you can do this, I insist. Plus we are we are going to make it sound really good’ and everybody loves it when it sounds good. And you go from there and achieve some rapport. It could easily not have happened.

As a producer do you drive these project or are you more like the facilitator.

Coming from the outside, and I’ve found myself in this situation over and over, everybody is there with a common goal so my task is to make it sound good technically.

Musically I want to do a certain thing because somebody has to count off and say, ’That’s too fast, that’s too slow, that’s too happy, that’s too sad‘. In other words, somebody as to be the camp councillor and if I do a good job and find a way to do it that’s comfortable and even democratic -- although conceptually someone has to be the boss. But I don’t mean The Boss, I’m not James Brown, I can’t do that. I have to stay within the context and see if we can push this down the road to see if we can make something good.

But I’m not the author of this, I’m simply the facilitator as you say. But we have to have some motive. It is intuitive.

You used to do a lot of soundtracks, why did . . .

You used to do a lot of soundtracks, why did . . .

I don’t do that anymore. I hate films, films make me sick now and if something makes me sick I always back off. They call you, you don’t call them. [Director] Walter Hill used to call me and we were friends and we understood one another. But there aren’t any Walter Hills anymore.

Mick Gentilli - Oct 5, 2009

I loved this interview. A subdued personality coupled with a sense of urgency, history.

SaveThanks!

merc - Oct 5, 2009

Really enjoyed reading this, thanks.

Savepost a comment