Graham Reid | | 12 min read

Nick Lowe: What Lack of Love Has Done (from Dig My Mood, 1998))

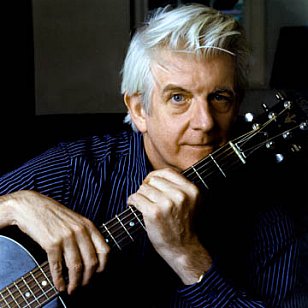

It is one of the ironies of Nick Lowe’s life that -- despite producing the first three Elvis Costello albums, the success of his solo debut Jesus of Cool in ‘78 (retitled Pure Pop for Now People in the more sensitive American market), being in the dream team with Cooder and drummer Jim Keltner on the exceptional John Hiatt album Bring the Family in ‘87 and having delivered a quartet of remarkable country soul albums this past 15 years -- in the consciousness of the greater public Lowe remains somewhat obscure.

The long career of Lowe -- once a fellow traveller with Elvis Costello who turned Lowe’s What’s So Funny ‘bout Peace Love and Understanding into a punk-era hit, and former son-in-law to Johnny Cash -- has been remarkable for its consistency and opportunities lost.

With the pre-punk band Brinsley Schwarz he wrote country-rock with a British skew, although the band blew their a high-profile career launch at the Fillmore East and journalists flown in could barely find a decent word to say.

Brinsley Schwarz played on, spilt up (some going on to Graham Parker’s Rumour), Lowe teamed up with guitarist Dave Edmunds for the much acclaimed Rockpile (critical respect, blistering live shows, public indifference) and then started recording as solo artist.

The Jesus of Cool album -- which slews stylistically from cynicism (Music for Money) to a Bowie pastiche (I Love the Sound of Breaking Glass) and dark humour (Marie Provost) -- was going to be his breakthrough. But it never really happened.

The Jesus of Cool album -- which slews stylistically from cynicism (Music for Money) to a Bowie pastiche (I Love the Sound of Breaking Glass) and dark humour (Marie Provost) -- was going to be his breakthrough. But it never really happened.

Aside from his own albums, doing solo shows, the work with Hiatt, touring with a small band and now with Ry Cooder, Lowe still manages to be a songwriter to order: he wrote The Other Side of the Coin for Solomon Burke’s 2002 album Don’t Give Up On Me.

His own material however on his last four albums (The Impossible Bird, 1994; Dig My Mood, ’98; The Convincer, 2001; and At My Age, 2007) has a darkness in the lyrics despite the effortless melodies which bring to mind Sam Cooke or Charlie Rich. And sometimes that’s a problem, as when he first started playing I Trained Her to Love Me which, despite the title, contains some deep self-loathing behind the braggadocio.

Droll, witty, and at 60 a new father, Lowe is a self-effacing raconteur and deals amusingly with his life in pre-punk bands like Brinsley Schwarz which had a reputation for great songs and heroic drinking.

This phone call catches you at an un-rock’n’roll hour -- and you’re up and about.

Yes, it’s unusual to be doing this kind of work at this time, it’s 8am, but I have a small boy so I am no stranger to this time.

You are coming to New Zealand with Ry Cooder, anything else on the horizon?

I’m going to the US actually. I have three careers: a solo show, sometimes with my band and this stuff with Ry.

But you tend to forget how to do it and so I’m at the moment going through the songs I do in my solo show and remembering how to be Nick Lowe.

Do you go back very far in that solo show, like the stuff you wrote for Brinsley Schwarz?

Not too many, but there’s a song I wrote which I thought was the first original idea I had that I do. Like everybody who starts writing you rewrite your heroes’ catalogue, everybody does. But the first original idea had, and I was shocked that it was an original idea, was What’s So Funny . . . which has become something of a standard.

Not too many, but there’s a song I wrote which I thought was the first original idea I had that I do. Like everybody who starts writing you rewrite your heroes’ catalogue, everybody does. But the first original idea had, and I was shocked that it was an original idea, was What’s So Funny . . . which has become something of a standard.

I can’t think of anything else from that era, but really will do anything as long as it’s not something that embarrasses the 60 year old man singing it, but some of it is a bit too callow.

Country Girl?

That’s not a bad one, there are far worse customers than that.

I want to talk to you about coming with Ry, but also about other aspects of your long and interesting career. You’ve never been to New Zealand before.

No, I just haven’t been asked. I’ve been to Australia two or three times, although I must say the Australians are quite resistant to my charms.

The first time we went with Rockpile, to be frank, we spent the whole tour extremely drunk and didn’t really make a good impression. Then I went back again a few years later with my band and that was better. But the last time was 12 years ago and I went with a drummer and keyboard player I still play with.

We had this glorified acoustic trio and God knows what it sounded like but we thought it was fantastic. We did all right with that. But we only did two or three shows.

The place you are playing in Auckland is an old picture palace, it is a beautiful room.

That’s right up our street and the sort of place Ry likes because they always sound so great as well as being easy on the eye.

This association with Ry, you first met in the late Eighties with the John Hiatt album Bring The Family?

Exactly. I used to know John Hiatt in the bad old days and we used to knock around town together and get into a few scrapes. And then he had this terrible tragedy and went underground.

Then he called me out of the blue and said, ‘Can you come and do this record with me, I’ve only got four days’. I managed to get Ry and he said he’d come along for a day and see if he liked it, but if he didn’t he’d clear off again.

Then he called me out of the blue and said, ‘Can you come and do this record with me, I’ve only got four days’. I managed to get Ry and he said he’d come along for a day and see if he liked it, but if he didn’t he’d clear off again.

But I was always such a great fan of his, and also Jim Keltner, and although I was going through a bad time myself right then I couldn’t let the opportunity to work with these people go by.

And it was a really good record because of its constraints in time and the way it had to be recorded in that short time.

In fact when the four of us decided to do a project later on as Little Village, conversely one of the reasons that didn’t work artistically was because Warner Brothers gave us as much studio time as we wanted and we slew the fatted calf. We just fiddled around and it was a bit bitsy and bit poncy.

I loved the whole thing about it, but I must say I don’t play that record very often.

Bring the Family is considered a cornerstone album in John’s career.

It was and the songs were so good. We had to sing them live in the studio so there was this fantastic atmosphere. And the songs were so stark it really worked.

You used to do a lot of production and on so many wonderful albums, especially in the Eighties. But you were very dismissive of what you were doing, I think you said once you could record a vole if you like the cut of its jib.

I don’t do any now, I stopped in the Eighties. I got more and more disillusioned. I have to be careful what I say because I don’t want to sound like a luddite, but when these so-called great strides forward with automation and computers and drum machines the fun really went out of it with me.

I used to far more enjoy going into a room full of people.

The same thing happens in every business really, you find out where the power lies. It might not be with the fancy lead singer who is on the cover of all the magazines, it might actually lie with the sulky bass player and the bloke you have to make friends with and get him on your side in order to get the fancy lead singer to behave.

But with computers you don’t have to worry about these things.

So I was never really a technical bloke, I was never interested in that. I was more interested in getting a vibe going and waving my arms around and getting people at it, and encouraging them to go further than they thought they could.

It also meant you couldn’t have some record company bloke telling you to go and do it again. When automation came in you could remix and remix.

In the old days you just slapped on their desk and said, ‘There is it’. If they wanted you to do it again you could, but it would mean starting all over again.

So I got very disillusioned and thought sod it. The last thing I did was in Nashville with the Mavericks, it was for the movie Apollo 13 which tells you how log ago it was.

I did a couple of songs with them. They flew me out first class and put me up in the finest hotel in Nashville and really all I did was stand in the back of the room in a good suit while a team of other people did all the work.

I thought, ‘This is a pretty nice gig, but it’s not really for me’.

As a songwriter you are an American at heart and soul -- Charlie Rich and Sam Cooke -- but with an English sensibility of wry humour and irony.

As a songwriter you are an American at heart and soul -- Charlie Rich and Sam Cooke -- but with an English sensibility of wry humour and irony.

No doubt about that, my influences have always been American. I love roots music, soul and folk and jazz. I listen to much more jazz now than I ever did.

But I loved what happened when it came over the Atlantic our way, and we had no idea how huge the US was and is, and those regional aspects.

Now of course I can listen to a record from the Sixties and tell you where it was recorded. Back then in the pre-Beatles period we had no idea about that, but we knew it sounded much better than what we had.

But the Beatles and Stones of my generation who are considered to be archetypal British bands, and the Kinks and the Who, were all influenced by American music -- even though they are thought of as British bands.

At their roots they were playing American r’n’b and in the Beatles’ case very country’n’western.

Yes, George Harrison’s playing was very Chet Atkins and Carl Perkins for a few early years.

Exactly. So I like what happens to American music when it comes here and we mix and match, which ironically the Americans have never been able to grasp. So we are selling their own stuff back to them.

Largely speaking Americans have very little knowledge of their own roots music because they never get to hear it, the radio stations don’t play that. Whereas radio in this country is really pretty good, a wide range from show tunes and rockabilly to obscure stuff.

I keep thinking I should have heard everything by now, I’m supposed to be something of an expert.

There seems to be this period between 1952 and 1966 when a bunch of aliens came down to America and made this unbelievable music and then cleared off. There now seems no sign these people were here at all except for a few busted old amps, some broken guitars in junk stores and a few old studios where they recorded.

There seems to be this bottomless well of this stuff. Every time you think you’ve heard it all something else comes along.

On your recent album there is a slightly disturbing quality sometimes. There is a real darkness at heart on I Trained Her To Love Me on At My Age for example . Where does a song like that come from?

I can’t remember that but the title came and you can’t send the idea back. That title occurred to me. I plead the Randy Newman defence where you say, ’It’s not me it’s a character talking’. But of course there is a certain element of you there, what you know or what you’ve observed, or have been rather guilty of seeing in yourself.

I have seen people like this and might even have behaved in this appalling way.

What Lack of Love Has Done is another a character song.

Yes, if you think yourself into a character on your way. When I brought up I Trained Her To Love Me, I played it on one of my solo tours to see how it would go over.

Normally you’ll find that most audiences if they hear something they are unfamiliar with they’ll give you a nice clap, but they to have heard it on a record. But that song divided people from the outset: one side were hissing feminists and on the other were these air-punching guys yelling, ‘Way to go, man’.

Talk about missing the point.

There were a few in the middle who took it as you are supposed to, as a funny song albeit with an uncomfortable grain of truth in it.

Johnny Cash covered your song The Beast In Me. Were you ever tempted to produce him?

I never thought I could bring anything to him. I was such a fan of his, I did record with him a couple of times but I was just in room. I was too in awe of him. I love Merle Haggard as well, but I couldn’t manage coming out of retirement to produce him because I couldn’t imagine what to tell him to do.

Can you write to order, for example for say George Jones.

Yes I have done. The last thing I did was for Solomon Burke and that was to order. I like doing that, it’s like making a suit for someone, sort of, ‘Inside leg and what colour would you like on this one, sir?’

You’ve moved to a very different place in your music in the past two decades so what was it like listening back to Jesus of Cool for its expanded reissue?

It was hard work listening to it again. I could hear the charm in it but as a songwriter I was thinking if I’d only taken a little more time and not rushed. I could hear a kid in a hurry, but that gives it its charm.

Everyone was in hurry back then.

Yes, it seems liked everyone had an idea and if it didn’t work then, ‘Well then, let’s give them this one’. The number of good things we must have chucked out the door . . . it makes you feel a bit queasy.

post a comment