Graham Reid | | 5 min read

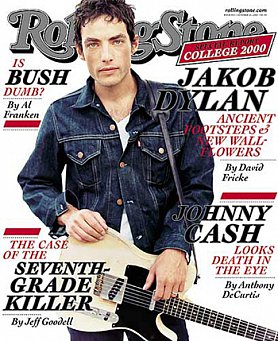

You gotta feel sorry for the guy. He's 32 years of age, is now on his fourth album with his band the Wallflowers, and still people want to talk about what he politely calls "the peripheral stuff".

You can guess what that might be when the guy's name is Jakob Dylan and he was the youngest of five children growing up with their dad Bob.

But the Wallflowers have a 10-year career behind them, a 1996 album Bringing Down the Horse which sold over six million and earned them two Grammys, and Dylan's written the theme to the new series of The Guardian, Empire in My Mind, which debuted in the States in late September.

Yes, Jakob Dylan is his own man but the wariness in his voice is discernible.

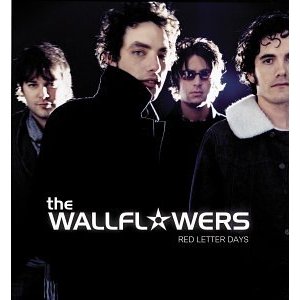

With the Wallflowers' new album - the chimingly melodic and often upbeat Red Letter Days - he's done a decade's worth of interviews adeptly sidestepping "the peripheral stuff" when it comes up. And on this day he's disappointed that interviewers haven't spent much time with the album.

He laughs that many have said it's an optimistic album, but that might be because they've just read the song titles: How Good It Can Get, Feels Like Summer Again, Here In Pleasantville, Health and Happiness ...

Anyone who fell that easily for a song title, however, is just asking for trouble, especially here where Health and Happiness is at best bittersweet and a fairly dark meditation on being let down by a lover.

So

although it carries a positive title, breezy and chipper Red Letter

Days isn't. But there is a sense of optimism at a time when many

American musicians are delivering their emotionally intense

post-September 11 albums.

"Yeah that's true, but I've written many songs and my responsibility is to just tell the truth and right now it is a little too easy and obvious to be writing songs that are negative and don't show any kind of hope. With these songs I wanted to show that I believe there might be light in the darkness.

"That doesn't mean that there always is and I don't believe this is a particularly happy record as people have suggested to me. In a lot of ways the record expresses disappointment and loss, but at the same time I feel I need to be helpful and I don't feel anybody at this point needs anything more negative thrown into their faces.

"What is there to be hopeful about? I don't really know, but I do know that I'm going to try every day to be hopeful and as we sit here at what feels like the brink of the end of existence I think being positive - whether it's a lie to yourself or not - gives you the opportunity to get through the day."

These days, especially with the career-vindicating Bringing Down the Horse album, Jakob Dylan has a lot to be positive about. His band works at a commandingly high level. They opened five nights for the Who at Madison Square Garden on their last tour two years ago, have songs on soundtracks (CSI, I Am Sam) and played at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in a show filmed for MTV.

Things weren't always so good - 10 years ago their self-titled debut arrived without a trace. They took to the road and sharpened their act (and changed their line-up) and broke through with the T-Bone Burnett-produced Horse. Tracks like One Headlight were inescapable on FM radio across the States and the album's songs were in the tradition of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers (Heartbreaker keyboardist Mike Campbell guested), the Eagles, classic Americana-rock and, yes, Dad.

Its phenomenal sales and their subsequent touring established the band outside the shadow of the father figure but Jakob Dylan says even at the time he was sceptical about their success. "Let's be honest, you sell six million records but six million are not coming back. That's not how it works. A lot of people are buying that record to stuff in the Christmas stocking - the record takes on a life of its own.

"At some point you lose it and it becomes everyone's record. That's a dangerous time and an exciting time ...

"When it went gold I just about had a heart attack, when it went platinum I didn't even notice because it was slipping away at that point. At the end of that record and touring we had plans to go to Europe and continue touring but I'd had enough. I'd forgotten what those songs were about and I didn't want to sing them anymore."

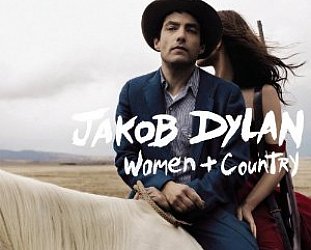

Dylan retreated, wrote at home, and the subsequent album, Breach, in 2000, was a nakedly emotional album of self-doubt, the hit-count considerably lower but a mature and affecting work anyway. They toured again and at nights he would go to his hotel room with his guitar and try to write.

"There are many different ways you can write - one is through discipline and another is through inspiration. But the truth is inspiration is not always there and you do have to rely on the mechanics at some point. On tour you have to work hard not to write songs about being on the road.

"I found that problem when finishing up touring Bringing Down the Horse and I got home and it was time to write songs. I'd been on tour for 2 1/2 years and did not want to write a song about the yellow lines of a freeway or about hotel rooms - those records are just kinda gross. Nor did I want to write about success either. You want to get back to some kind of life which has substance and write genuine thoughts again.

"So, previously I'd written when I had a break. But for this album I wanted to put an end to that and I find writing on the road extremely challenging. We all have these romantic ideas we can write on tours but you can get lost on tour sometimes and writing can be difficult.

"I

took my guitar to my room and wrote in the confines of a small space

by myself which is how I write at home as well.

"I've

been on tour and felt the weight of time slipping past me that I

could be using better.

"I wanted to make sure that it didn't happen on that tour."

Red Letter Days is a return to the strong writing of Horse and again Dylan's voice sounds less like his dad's than Bob's bandmate in the Traveling Wilburys, Tom Petty. Elsewhere he writes and sings in a manner which echoes Canadian folk-rocker Bruce Cockburn, and only a fool would deny the similarity between the delivery of the verses of When You're On Top with his father's A Hard Rain's Gonna Fall.

But elsewhere he explores his own dark stuff, especially on the nice'n'nasty Health and Happiness.

"I wouldn't want to say who it was about," he laughs. "It's just in terms of feeling disappointment and I think we are all aware of the feeling of letting people down one way or another."

And on this otherwise hopeful album, what about the apocalyptic Everybody out of the Water?

"Well, I find it difficult to express what songs are about and hopefully they explain themselves," he says sounding very much the son of his elliptical and elusive father. "Whatever you think it's about is what it is - but I suggest in the last line that it will get better. And it will get better. But until then, keep the hell out of the water."

post a comment