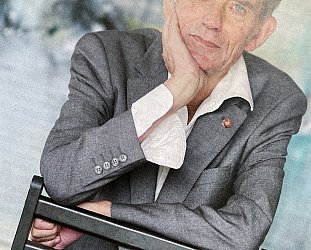

Graham Reid | | 5 min read

The Verlaines: Doomsday

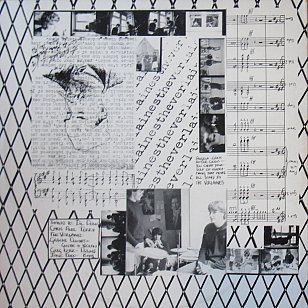

Quite why anyone thought there ever was a "Dunedin sound" is bewildering -- without even hearing a note of the music all you had to do was look at the cover of the famous "Dunedin double" album of mid '82 to see how each of the four bands -- the Stones, the Chills, Sneaky Feelings and the Verlaines -- thought of themselves and wanted to portray that to the world.

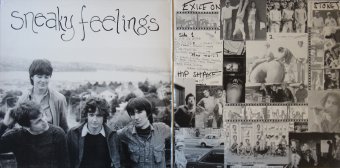

On their self-designed space on the cover (below, left) Sneaky Feelings had the most traditional image with the four band members together directly in front of the camera.

The Sneaky's Matthew Bannister later said in his book Positively George Street (the title of an early Verlaines' song) that they wanted it to refer to the Beatles' album With the Beatles -- and thus betrayed their pop ambitions. They had named themselves after one of Elvis Costello's most commercially acceptable pop songs. Mainstream pop acceptance is what they were after.

For their side of the cover (far right) the short-lived Stones amusingly copied and parodied the Rolling Stones' Exile on Main Street. They weren't taking this thing seriously and there was a bit of boyish posturing on display.

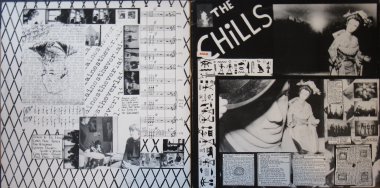

For their space the Chills' Martin Phillipps wrote out his lyrics (he wanted to be taken seriously although they were somewhat addled) and Bannister notes that the hierogyphics suggested "drugs".

And the Verlaines . . .

Well, the band name tells you something (Paul the poet, not Tom of Television) and their cut-up cover had musical notation from the score of a song, an image of Paul Verlaine and an art school collage quality.

Here too are song lyrics -- and words as much as music was what Graeme Downes of the Verlaines was about. That would become increasingly clear over time. And for Downes, the album was an artefact.

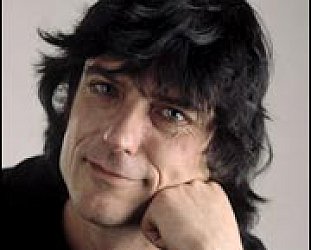

Downes (interviewed here) was classically trained and would freely concede (see interview here) that rock music wasn't his idiom at the time: "I knew about music theory and complicated chords and a lot of classical theory, but I didn't know diddley-squat about rock music and what made a rhythm section function."

That would come -- but even right from the start literary and musical aspiration went hand in glove and on the Dunedin Double (their three songs recorded in an afternoon, the Sneaky Feelings had the morning session at the house in Barbados St), the Verlaines posited themselves as band apart, even though their defining moment in their early career wouldn't come until Death and The Maiden released exactly a year later.

On that song, the title from an Edvard Munch painting, the lyric referencing Paul Verlaine, their intellectualism was married to a driving rhythm and a terrific hook.

But on the Dunedin Double they -- Downes, drummer Greg Kerr and bassist Jane Dodd -- were still making tentative forays into rock: Angela is a driving acoustic number, the five-minute Crisis After Crisis offers the first hints of their energetic, rhythmically propulsive rock and Downes' strained but effective vocals which would become an early identifying feature, and You Cheat Yourself of Everything That Moves is one of those songs where the lyrics are barely audible behind the lo-fi, incessant strum of increasingly urgent guitars.

After the Death and the Maiden single and the EP Ten O'Clock in the Afternoon of '84 (which included their live favourite, the tense Pyromanic), it was the exceptional Hallelujah All The Way Home album which confirmed the band's reputation -- and that of Downes as one of the most emotionally interesting, poetic and expressive writers on the fledgling Flying Nun label.

Hallelujah -- in a gatefold sleeve at a time when such notions belonged to the bloated prog-rock era -- was a work of obvious and visible ambition.

Opening with a melancholy piano and the lines "Well hello there sordid inmates, you got fences around your necks . . ." before embarking on what would become a Verlaines' signature sound of rapidly strummed guitars, Hallelujah is an album of musical tension-release, changes in time signatures (the complex The Lady and the Lizard with its quasi-classical elements interposing themselves within the stabbing guitar rhythms) and unexpected twists and turns, some of which seemed to draw on Anglofolk as much as rock music. This was listening music.

The

band came into its own with the double-whammy follow-ups;

the Doomsday single in '86 and the Bird Dog album of the following

year which brought in even more musical elements, notably jazz

musicians Rick Robertson (saxophone on Only Dream Left), and George

Chisholm (trumpet) with Merv Thomas (trombone) on the reworked CD, Jimmy Jazz and

me -- the title of which referred to Claude Debussy and James

Joyce.

Bird Dog is the Verlaines' finest moment in their early career: the tension between rock and classical which co-existed within Downes is almost palpable but had been brought into more harmony than previously on songs which could be gorgeous (the opener Makes No Difference) or thrillingly complex and full of nervous tension.

There is simply nothing like Slow Sad Love Song -- with its bass notes from the deep underground, swirling and thrillingly tense string part and the strained, aching and anguished vocals -- anywhere else in the Flying Nun catalogue.

And as he would frequently do -- and he was rare in this regard, the Verlaines' Corporate Moronic album of '09 was full of satire and swipes -- Downes wasn't beyond making social comment wihtn the context of his poetic lyrics.

So Bird Dog is shot through with drama, keen

observation, personal soul-baring, literary turns of phrase, brainy rock'n'roll and themes

which have often preoccupied him; booze, dying or dead love, and the

spectre of death. All fine subjects in literature.

If Bird Dog was going to be hard to equal -- and some felt that might be impossible -- what followed was either confirmation of the Verlaines' special place in New Zealand's musical landscape, or a disappointment. Some Disenchanted Evening of '89 (with Mike Stoodley replacing Jane Dodd on bass) divided reviewers but was nontheless a work of often dark grandeur although many also read it as musically more conventional.

Yet "conventional" was never an appropriate adjective for a band like the Verlaines.

Right from the start -- as the reissued Juvenilia collection of early material confirms -- Graeme Downes was a singer-songwriter with a unique perspective on what was possible in rock, but was also far too smart too fall for prog-rock as his vehicle.

Juvenilia is the ideal starting point on a journey of discovery if the Verlaaines -- whose music has long been hard to find -- are still new to you.

It has their cornerstone songs -- Death and the Maiden, Doomsday, Joed Out, Pyromaniac -- alongside those which expand your understanding: Crisis After Crisis, CD Jimmy Jazzz and me.

With the Flying Nun label resurrected and rescued in 2010 after years of being almost moribund, it is fitting that these early albums by one of the labels longest running, most interesting and always challenging bands should be among the first back in the marketplace and popular imagination again.

post a comment