Graham Reid | | 19 min read

Patea Maori: Ngoi Ngoi

The old wooden Methodist church in a

side street in Patea isn’t used much anymore. A lot of places in

Patea aren't. It's a town battered by the economic ideas of

successive governments and people have had to move out.

The work just isn’t there anymore.

But at least once a week the cobwebs in

the church rafters shake when the Patea Maori group, the town's most visible

success story of the past four years, use it as a rehearsal space.

It’s the Monday night before the soon

to be doomed Neon Picnic and the group has gathered to run through

its set and organise transport for the coming Friday.

They are supposed to open the festival.

Enthusiasm is high and members have

come back from as far away as Wellington to get things just right.

But it’s not an intense situation.

There is a lot of laughter and nobody seems in any hurry to leave

when things finally wind down around 8.30, three hours after the

20-odd members gathered in the tiny room.

The group is feeling good for a lot of

reasons. The forthcoming festival, the rehearsal going well and, best

of all, the new album Poi E has been out a month and is selling steadily

and quietly.

Currently available only on cassette

-- the album and CD versions will be available later this month -- it

has sold somewhere close to 2000 copies, a remarkable sales figure

considering it was deliberately released with no media ballyhoo and

has so far had no ads in the music press.

The album marks another milestone in

the Patea Maori group story, one which is well known for the

involvement of the club's prime mover and producer, Dalvanius.

The new album is very much Dalvanius’

brainchild -- and a complex and tightly integrated one at that.

It draws together threads of Ngaa Rauru

traditions with a sure sense of belonging to the Patea/Hawera area

where this sub-tribe of the Taranaki peoples live.

It incorporates traditional lyrics –

lyrics from various kaumatua and the contemporary synthesiser sounds

which were the hallmarks of the Poi E single . And flying men.

Flying men?

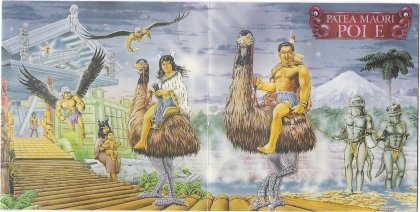

The highly-coloured album cover by Joe

Wylie -- from ideas by Dalvanius – is a clue to the contents.

Half-men, half-tuatara figures emerge

from water in front of Mt Taranaki and are held on a rope by a

warrior mounted on a moa. Above, winged men, the kahui rere, swirl in

flight.

Dalvanius laughs and confesses a

childhood passion for comic book heroes ("The Phantom and

Mandrake were my favourites") and how he would like figures like

the kahui rere developed into animated feature films to give Maori

their own indigenous heroes.

But there is also something quite

serious in the imagery of the kahui rere and men riding moas.

The Takirau Marae is nearly 50km up the

winding Waitotara River valley, nestling in a warm bowl of green

fields under the high cliffs.

It is at the northern apex of the

traditional boundary of the Ngaa Rauru people and is a focal point

and refuge for Dalvanius and the members of the Patea Maori group. It

was here Dalvanius came to consider the direction of the music and

most recently to compose with Sonny Kauika Stevens, a kaumatua of the

Ngaa Rauru people.

It is here too that the kahui rere

settled after flying up from the coast.

The traditional belief in the flying

men is unique in Maoritanga -- possibly in Pacific history. According

to S. Percy Smith, writing in 1910, “a placenta was cast into the

sea and in due course became a man whose name was Whanau-moana or

Sea-born. He had wings, as had all his descendants. At first none of

these beings had stationary homes, but flew about from place to

place, sometimes alighting on the tops of mountains . . .“

The last of these people was named Te

Kahui Rere.

“The kahui rere are my ancestors,"

says Dalvanius, “and as a child of Ngaa Rauru, my tribal

affiliation on my mothers side, it‘s something we grew up with.

They were our tipuna, our ancestors, and are not just mythological.

They are part of our living being."

He points to the high cliffs and

indicates tapu areas where he says bones of the kahui rere are to be

found.

Ngaa Rauru traditions also speak of

domesticated moa in this area.

Since the death of Ngoi Pewhairangi in

early 1985, he has come to this place more and more often.

The relationship between Dalvanius and

Ngoi Pewhairangi has often been told, but bears retelling.

“She was the woman who wrote E Ipo,

the song that I produced for Tui Teka. On a tour of the East Coast

with Tui she sent me a message to me saying if I went past her house

she'd kill me,” he laughs.

"So naturally I thought I’d

better go and see this woman who had written the song. In fact the

version she'd heard and didn't like was one he‘d done in Australia.

“So I went to meet her and ended up

staying five, maybe six weeks. We just kept writing songs together

and comparing politics.”

At the time, he admits, he was "a

textbook Maori" in terms of his knowledge of the language and

Pewhairangi was committed to a reawakening of the language in people.

"She was a very political figure,"

says Dalvanius,” “and had headed a movement called Te Ataarangi,

The Awakening".

But his work with Pewhairangi cost him.

“I got ostracised by a lot of people

for working with someone from Ngati Porou. However, we had formed

such a strong bond it was water off a duck's back to us. She was a

tohunga and a matriarch – and a very strong person musically and

politically. People look at our songs like Poi E and think they’re

just Maori songs with a dance beat, but they are quite wrong."

The long-awaited album should lay that

misconception to rest. It is a concept album in the nicest possible

way, free of the grand conceits that the label “concept album"

suggests.

Dalvanius calls it "a living

memorial to Ngoi” who died when he and Patea Maori were in England

as part of their British/American tour in ‘85.

The death of Ngoi Pewhairangi and some

club members in the intervening years, and Dalvanius becoming

involved in the soundtrack to the film Ngati, meant the Poi E album

was put on hold.

"The fact that it got released at

all is a milestone in itself," he laughs, “and its' selling so

well is a bonus.”

The deaths in the whanau also meant it

deliberately came out quietly before Christmas without the usual

media hype surrounding such things.

“I don’t see that as being off any

consequence," he says about press publicity. “The single Poi E

was a sleeper, it took l8 months to happen and this album is

something that’s going to sell from now till the end of time."

The album begins with a recording of

the sea by the late Greg Carroll, Dalvanius' cousin and road manager

of U2 who was killed in 1986. The journey from Hawaiiki is sketched

in with aural references and by narrator Don Selwyn.

Ko Aotea, the second track, is “an

old chant which is strictly ours in Patea” and speaks of the Aotea

canoe, a replica of which stands in Patea.

The fourth track illustrates the

complexity of imagery Dalvanius is working with.

The waiata are by the late Ruka

Broughton, the noted Maori scholar who wrote his MA thesis on "The

Origins of Ngaa Rauru" and Hoani Heremaia, “the living prophet

for Ngaa Rauru and Patea Maori.” A haka in the middle by Patea

Maori is about the taking of the Parihaka land by the constables.

"The waiata sung by Hoani says,

‘When this one man died all Maoridom stood still' and it could be

referring to Te Whiti, Tohu, Tawhiao . . . or Ruka Broughton. For me

they were all prophets,” says Dalvanius.

The album also touches some deeply

personal bases for him.

"In Maoridom there are a lot of

Romeo and Juliet romances and that's what my parents' was like. What

Ngoi and I wanted to do on the song Ngakau Maru was to state that

close-knit base of rural Maori families. The lyrics express the total

loss my mother felt when my father died and in turn what I

experienced when she died.”

The traditional song of farewell, Hei

Konei Ra, takes out the first side . . . but with the distinctive

Dalvanius production job.

"Everyone in the studio calls me

Dalvanius De Mille,” he laughs about his widescreen sound. "My

ultimate hero is Phil Spector who either made some classic or a real

bomb.”

Talk of his production method leads him

into a conversation about how he thinks about sound.

“A lot of musicologists say the Maori

had no percussion. We did. We had stones we used like castanets and

certain trees were used as warning about marauding tribes. They can

be considered percussion.

“But nobody thought of the swishing

of the pui puis as percussive. In the studio I mike up all the pui

puis separately and in the track Taranaki Patere-Kahuri there’s

nothing but the pui puis.

“The traditional poi was made from

raupo which also has the most amazing percussive sound. I had a close

up mike on each of the pois, too.”

The recording studio where he compiled

the separate tracks dating from as far back as 1983 is a long way,

physically and emotionally, from the Takirau Marae where he comes on

the Tuesday morning to speak with Sonny Kauika Stevens.

Stevens has written the words to a tune

telling young people to hold fast to their language. It is written

with the kohanga reo in mind and takes its first lines from T.W.

Ratana, the religious and political leader from the Wanganui

district.

Stevens is the guardian of much of the

Ngaa Rauru people's history and in the warm valley under the imposing

hills where the kahui rere once flew, his presence is met with a

natural respect.

Stevens is a naturally modest and quiet

man and speaks in a low voice about the song.

"It says hold fast to your Maori

language because it is something handed down to our tipuna from our

Supreme Being, It says be strong and hold fast.

“We put this together when I came

back here to get in touch with my Maori roots," says Dalvanius.

“Coming here you know these people, the tangata whenua, are

committed to this thing.

"I don‘t like all these

part-time Maori Affairs tutors who are weekend Maori. These people

here have their hands in the dirt and just about everyone in Patea

Maori has roots relations here.

"The marae is our last refuge."

The Takirau Marae, however, is more

than a retreat for Dalvanius. He is hoping to establish a women’s

refuge in the area and is currently negotiating in conjunction with

the people of the marae for better amenities.

But there is another reason for him

coming here this particular morning. He wants to record the song for

Stevens so the people can learn it.

Inside the wooden dining hall, a huge

tape recorder miraculously appears as it from nowhere looking

incongruous in the battered, empty building.

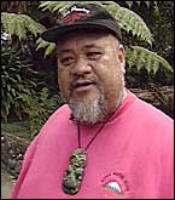

Dalvanius settles himself on to a chair

in front of the tape recorder, his 20-stone plus figure bulging under

his distinctive pink tracksuit. He picks up the glitter and indicates

that he composed the tune on piano so we should forgive his

guitar-playing.

The room goes quiet and the half-dozen

people who have wandered in move outside so as not to create any

distraction.

He begins to sing.

His voice is clear and confident and

it’s a curious moment.

His massive pink figure is bizarre in

the room where the cool air is buzzing with flies.

Aside from the music and the flies,

everything is quiet and still.

Outside, the hills blaze a rich green

under the clear blue sky and even the most cynical of city-born

hearts can feel a special, almost timeless and mysterious, quality

about the place and the day.

He finishes the song and rewinds the

tape to overdub the first harmony part.

He does it again and again with each

harmony lightly different from the last.

The tune is finished and he turns to

the door and yells, “Yeah you can come back in now.”

The magic moment is broken as the

laughter from Stevens and his family brings the real work back into

the room.

“Before I went overseas with the club

in '85, “Dalvanius has said earlier, “Ngoi said she wanted to

tone our relationship down because she felt it was time I worked with

others preferably people from Taranaki, my own people.

“Sonny is a kaumatua, very much like

Ngoi. He has an aura about him and he uses what I call the classic

Maori language. A lot of the old words are dying for want of use and

the classic Maori is being lost for the convenience of the new

Maori."

He illustrates the “new Maori” by

words like niupepe (newspaper).

“I see my role as working with people

like Sonny who have that gift of using classic Maori and that‘s why

I’ve chosen to remain here"

He has some especially cutting

comments, largely unpublishable, about "weekend Maoris" and

those from certain government departments who would tell the people

on the various marae in the district, nine of which make up the

Rangitaawhi Trust - the self-help scheme which has grown up in Patea

in the wake of the closure of the freezing works -- how to live.

“These people here,” he says

pointing emphatically around the Takirau Marae, “are the real

people who are in touch with Maoritanga. Some people said to me I was

just cashing in to make money out of the Maori and I say, 'What

money?' If I just wanted to make money I know which side my bread's

buttered on. I sang a club over Christmas and got the money to paint

my house.

“If I sing in English I get me award

rate, if I sing in Maori it’s negotiable. That’s the fact, but

that's not the Pakeha's fault. It’s ours. We’ve allowed everybody

else to make money out of our language but ourselves."

In that sense, he is an unashamed

hustler who knows facts and figures about record sales, what kinds of

fees to ask for, and how to work in the Pakeha system. It makes him a

formidable opponent across a negotiating table and probably a very

unpopular one from time to time.

However he has done it: taken Patea

Maori to the top of the New Zealand charts and around Europe and

America.

In 1989, the group embarks on a

coast-to coast Stateside tour and the plans don‘t stop there.

The Poi E album is part one of a bigger

scheme. It is the Maori songs for a stage show about a young Maori

boy reaching out to find himself and is, he admits, autobiographical.

“The musical, Raukura, will show how

disoriented as a people we are. We’re always blaming the Pakeha but

how much can we look at ourselves in the mirror and ask if we aren’t

also part of the perpetrators of our own genocide. I think in a lot

of ways we are . . . and saying that has got me into a lot of

trouble," he laughs.

"The album is the Maori songs and

the second part, which is going to take several thousand dollars, is

the English part.”

Get Dalvanius talking - and he'd be the

first to admit that's not difficult – and the schemes and ideas

pour out of him. He envisages three separate Patea Maori groups

touring the world constantly.

He has written dozens of songs, with

Ngoi Pewhairangi, with Stevens . . . and the Kohanga Reo Rap song is

still waiting in the wings.

"It was supposed to be on the

album but I decided not to put it on because it’s got English in

it. I wanted the first album to be a memorial to Ngoi who always

reminded me to speak Maori if I ever answered her in English."

But that is just the music side of

thing.

Back in Patea, the Rangitaawhi Trust

looks after a number of job schemes, all of them involving Patea

Maori group members.

Around the corner from the old

Methodist church is the abandoned sewing factory, now turned into a

carving school under the tutelage of Patrick Davis, one of the

trustees and, naturally, a member of the Patea Maori group.

On the floor is an impressive honours

board being carved for the Patea High School based on designs from an

old god stick found in the Patea River.

“The design is not quite the same as

the god stick," says Davis, "but it nearly is. You don't

actually copy those sorts of things. We‘ve done carvings for the

hospital and the primary school too . . . and this,” he gestures

towards a huge carved piece nearly two metres long and awesomely

heavy, "is a gateway for the high school."

The carving school, an Access scheme,

has had a number of young people go through it. Currently there are

half a dozen people at work including a number of women whom he has

started off on cattle-bone and, when it’s available, whalebone

carving.

"When the first group went off to

America, one of the club's members had a tiki made of beef-bone.

Someone there thought it was whale and offered him $500 for I,” he

says laughing. "But he wouldn't part with it – he was afraid

they’d find out it was just beef."

The bone and wood carving are offered

for sale around the corner at the Poi E centre and occasionally as

far afield as Auckland.

Some of those who have been through the

carving school are now tutoring in other similar schemes. One

ex-student is now in charge of a group of eight in Hawera.

"With the closing of the freezing

works,” says Dalvanius, “there has been a revival of the true

tikanga of our people including the waiata, the music, and especially

of Taranaki carving. That honours board made after the style of a

piece of local traditional carving is true Ngaa Rauru art. Classic

Maori art.”

Directly across the road from the

carving school is another facet of the Patea survival story, once

again part of the Rangitaawhi Trust. It's an engineering school run

by John Matthews where students on a 20-week Access scheme learn

basic engineering skills.

“Basic is nothing though,” says

Matthews. “You can‘t just teach people a few basics and then

expect them to get a job in engineering. You've got to have basics,

intermediate and advanced levels. That's how you get a vocation. I‘ve

submitted my programmes to the people in Wanganui but I don’t know

if they'll accept them.

"If they say no, then that's it.

But what these people here have achieved," he says pointing to

the half dozen young men and women at work over noisy machinery, “is

really something phenomenal.”

The Poi E Centre around the comer on

the main road through Patea is where most of the products of the

workshops end up. Inside the small unprepossessing office opposite

the replica of the Aotea canoe are items from the weaving, carving

and engineering modules. Iron tables, carved bone and wall hangings

are displayed and most of them are for sale. It is likely the new Poi

E album will also be on sale here too.

Just outside town, on a high vantage

point overlooking the mouth of the Patea River, is another marae

where past and present for the Patea Maori mingle.

The Wai-O-Turi marae houses a kohanga

reo and three members of the group work the land on yet another

Access scheme.

Dalvanius points to the river mouth

where he goes to think through musical ideas and comments on how

herring used to be plentiful here.

The marae is named for the freshwater

stream of Turi and Rongo Rongo and the young men clearing the land

stand on the trenches dug out of the land hundreds of years back by

their ancestors.

One of the women gossips with Dalvanius

about the "weekend -Maoris" who have been created by the

devolution of Maori Affairs and now come down and tell them how to

run the marae. They’ll get the sharp end of her tongue if they are

foolish enough to try it on, she says.

Behind her is a huge and healthy

looking vegetable garden, some of the produce of which ends up in the

small vege shop in town halfway between the carving school and the

Poi E centre. It’s another side to the Rangitaawhi Trust which

unites the struggling town.

For outsiders, Pakeha in particular

perhaps, it is an unusual experience to see such a broad-based

self-help scheme and you can’t help but wonder what keeps it going.

And then you catch it in small things,

none of them to do with money or profit.

It’s in a song in a roughly hewn

dining hall under hills where men once flew. Or standing on marae

fortifications where people are clearing the land again.

And in a fleeting image in an old

Methodist church.

Dalvanius is working the tape recorder

with the prerecording backing track for the song Ngoi Ngoi written

about Ngoi Pewhairangi, the next Patea Maori single.

“After her death," he has said

earlier, “I asked the people at Tokomaru Bay for a line each about

her. But everything they said sounded so sad and the woman was such a

celebration. I remembered the gospel churches I went to in New York

after I'd heard about her death so I kept the lines but made the song

into that kind of gospel celebration."

The backing track begins and the group

breaks into a collective smile and sing the celebratory song. And up

on the old pulpit a child, no more than six, sits with her legs

dangling over the edge.

It is late and she is tired. Yet as the

song begins she sings along, the poi in her hand swinging freely.

She stares off into some far distance

as tiredness makes her eyes unfocused, but there is a spirit in the

music which makes her sing.

It is the same spirit which moves

through this place. This land. This Aotearoa.

Chris Gaskell - May 13, 2010

Beautifully-written piece Graeme - vividly captures Patea and its people at that time. Hard to believe it's more than 20 years ago - with Dalvanius long gone, I wonder what it's like now?

SaveJohn Ringer - Sep 5, 2016

And now the film, which I would rank amongst our best ever. A stunning testament to some very special local culture that had me in tears (moving and laughing tears) for much of it. I'm not sure how much, if any, supporting funding went into the movie, but it certainly should have been well-supported. Beats the heck out of NZ on Air taxpayer money going into execrable reality tv. Poi e is where our heartland is - in the small towns and communities that keep getting hit but get up and keep getting on. I guess Tearepa Kahi's off to Hollywood now, though I bet Bollywood would also welcome him with open arms. A genius, like his bro Dalvanius. And here's to all those old unsorted forgotten drawers.

Savepost a comment