Graham Reid | | 4 min read

Somewhere There's a Girl (1961)

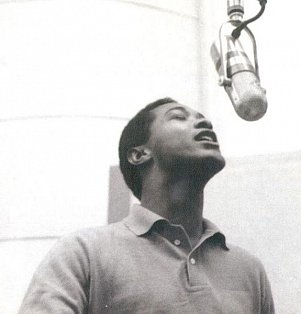

At this distance, we can’t be expected to understand what the

death of Sam Cooke in the sleazy Hacienda Motel in ’64 meant to

black Americans.

The former gospel singer was found slumped against a wall –

naked except for an overcoat and one shoe, gunned down by the motel

owner after a woman he’d picked up in a bar had fled his room

claiming he attempted to rape her.

It was the very public fall of a black hero, a man Jerry Wexler called “the best singer who ever lived, no contest".

Cooke was

the good-looking one who crossed race barriers by virtue of the

refinement of sheer natural talent. At the end, however, issues of

fame, success, colour and various ideas of truth all came to the

fore.

Does this sound familiar?

Cooke – like Michael Jackson – died in strange and sad circumstances so there is the similarity and the convenient circularity of a closed career. History books are best served by such symmetry.

But Cooke and Jackson

couldn't have been more different.

On paper, Cooke’s was the more familiar story.

Born in the

crucible of the blues in Clarksdale, Mississippi -- where Robert Johnson allegedly made his pact with the Devil at the crossroads -- he moved with his

family to Chicago when the Depression hit. That's the blues mythology

and cultural journey right there. Cooke’s father was a man of

the Lord and gospel was Sam’s calling, too.

He grew up knowing Aretha Franklin’s preacher father and doo-wop

was on the street-corner and the radio. In 1950, Sam joined the

famous Soul Stirrers at their invitation. But his style was

different: “He didn’t want to be that deep pitiful singer,”

said fellow Soul Stirrer S. Roy Crain.

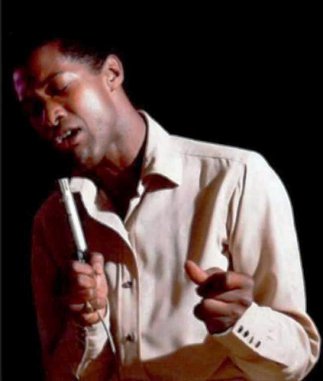

Cooke wrote for the Soul Stirrers and became their producer, and then moved effortlessly into pop and won hearts with the gravity-defying You Send Me and songs such as Cupid which sent a chaste arrow straight to the heart. It was simplicity of sentiment made eloquently transcendent.

Pop had its Raphael who could render

the secular as the sublime.

Cooke was smart, too. In ’59 he started his own SAR record label

with Crain and J.W. Alexander.

The 30th anniversary of Cooke’s death in December '94 went

largely unnoticed (a marketing opportunity lost for RCA Records and

others who controlled his most popular recordings) but acknowledgment

came from an odd corner.

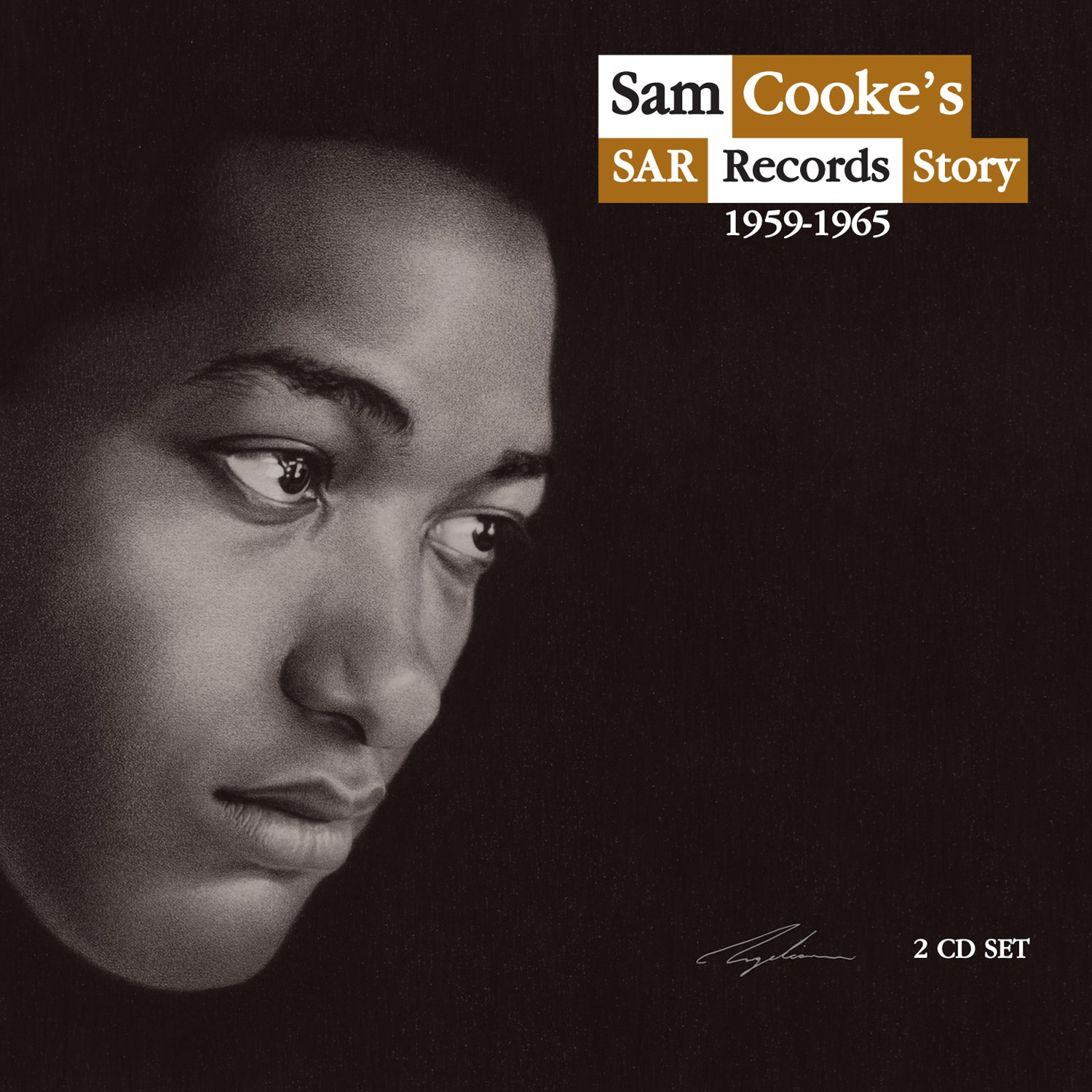

The fiscally inventive former Stones/Beatles manager Allen Klein still controlled the SAR label and released what superficially appeared to be a Sam Cooke box set, Sam Cooke’s SAR Records Story.

But it was actually something more.

The double-disc collection with accompanying booklet (which

avoided the messy details of Sam’s death) was a big, but not

formidable proposition; the first disc being gospel, the second the

secular material SAR produced.

Cooke, however, appeared on only half a dozen tracks (although he

produced and/or wrote almost everything) and the great Bobby Womack

featured on just as many, including the classic Cooke-produced It’s

All Over Now from ’64 which the Stones covered the same year.

None of Cooke’s pop hits appeared -- a rough run-through of You

Send Me hardly counted - so the set was the sound of SAR rather than

Cooke specifically, but as such it allowed a look at that crossover

territory where the pulpit and pop shared a common currency.

None of Cooke’s pop hits appeared -- a rough run-through of You

Send Me hardly counted - so the set was the sound of SAR rather than

Cooke specifically, but as such it allowed a look at that crossover

territory where the pulpit and pop shared a common currency.

Street

soul was just around the corner, but in ’59 the world had yet to

feel the full impact of Cooke, Aretha, James Brown, Little Stevie

Wonder and others.

In songs such as the Soul Stirrers’ Praying Ground from 1960

(with lead vocal by Jimmie Outler) and R.H. Harris' Somebody from '62

you can hear an earthy pop style coming through and a simple shift of

lyrics in the Stirrers’ God Is Standing By could have been a Cooke

ballad he would take to RCA two years later.

Cooke’s sole gospel outing on the set, That’s Heaven to Me,

comes with his typically understated delivery but suffers from his

sentimental string arrangement.

The disc of pop songs showcases his nascent pop talent better,

particularly in the melodically familiar Just for You (a kissing

cousin to Wonderful World of the previous year) and his reworking of

Somewhere There's a God as Somewhere There's a Girl with the Womacks which he wanted to release but didn't. It was pulpit meets pop.

Sentiment is strong in most of the material but the simple

craftsmanship of Cooke’s writing carries even the weaker material.

In retrospect it is clear Cooke never fully realised his talents. He

was killed just as the world of pop was changing and it’s not

impossible that, like Brian Wilson, he might have made the transition

from pop-meister to elaborate sonic designer. Like Wilson, he had the

studio experience.

The artfully grainy cover shot on the box set presents him as a

dew-eyed sensitive man-child looking into the darkness.

And maybe -- for a short time in a complex life overshadowed by a death which described the arc of a fallen angel -- he was.

.

We bring this collection to attention because it has just been reissued as a four record set on vinyl

Rosco - Jul 16, 2024

Love Sam Cooke. In amongst the dark and the religious were the more mischievous. A personal favourite being Smoke Rings off Mr Soul from '63:

SavePuff, puff, puff

Oh you can puff your cares away, hmm-mmm

Puff, puff, puff, night and day

Blow, blow them into air

Silky little rings

Oh little smoke rings I love

Please take me above, with you

post a comment