Graham Reid | | 7 min read

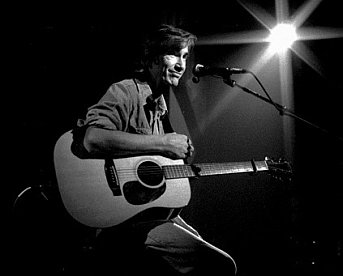

Townes Van Zandt: You Are Not Needed Now (live, 1985)

You hate to say lt, but Townes Van Zandt had probably already written his own obituary - many times. Try this as a sample of his cut-to-the-bone, white knuckle lyrics: “There ain’t much I haven’t tried -- fast llvin’, slow suicide, I try to tell myself I’m fine but it just aln’t so.”

Van Zandt has always lived on that knife edge of self-doubt, a man with a great future behind him. By his own admission he’s a manic depressive who can’t recall certain periods of his life, they’ve been lost in the slip of consciousness and an alcohol haze.

But this folk/country cult figure is still here and doing it -- and that despite a 1973 album entitled The Late, Great Townes Van Zandt.

“That was kind of a joke," he says from his home in Nashville in a gentle laconic drawl which sounds world-weary in an amused and detached way.

“The guy who ran the record company was a good friend and he maybe thought if the record had come out six or seven years earlier it would have been have been in the middle of all that folk boom."

"My mother didn’t think it too funny because of the way I was living at the time. I hadn’t seen her for a long time and she had no idea if I was in Mexico or the mountains or wherever and, all of a sudden, this album comes out with ‘the late, great’ on it.

"She started getting calls from all over and people telling her how sorry they were. It was a couple of months later and it dawned on me I hadn’t spoken to her for a while so I gave her a call.

“She was real relieved -- the Call from beyond," be says laughing.

Van Zandt doesn't laugh much in the course of the half hour conversation - but then again, he has had very little to laugh about in his life. He is a great ignored talent in American music and even now after his song have been recorded by Willie Nelson and Merle Haggard (who chose his Pancho and Lefty as the title track of their duo album in ’82), Emmylou Harris and Jerry Jeff Walker he still doesn‘t play all that olten and his albums only trlckle out.

"Last night was great though," he says. “I play about once every two years here in Nashville and last night I was at a place called Douglas Corners. Guy Clark was there, and Rodney Crowell. Lyle Lovett too. So it kind of turned into a scene. It was fun and I guess I played for a couple of hours."

Those name checks and acclaim from equally talented peers like Butch Hancock, Bob Dylan and Steve Earle (who says Van Zandt ls the "best songwriter in the whole world and I‘ll stand on Bob Dylan's coffee table in my cowboy boots and say that”) illustrate the kind of regard this quiet singer/songwriter is held in.

For himself Van Zandt is modest and wry about the recent acclaim since Pancho and Lefty and the duet by Emmylou Harris and Don Williams on his song If I Needed You.

“I’ve met Bob Dylan's bodyguards and if Steve Earle thinks he can stand on Bob Dylan's coffee table. he's sadly mistaken," says Van Zandt.

But things are better these days. A stable marriage, a new family - his son, Will, is five and a half - and the dark days largely behind him.

“For a folk singer, which I consider myself, I've done well. I’ve never i tried to be a straight country singer and never had a country band. Back when I was deciding I figured I wasn't the sort to dress up and play country fairs, but for a folk singer it was a whole different circuit.

"It’s nice my songs fit into country music and that's where I’ve been classified. The records are classified like that too, everything has to be classified I guess," he says wearily.

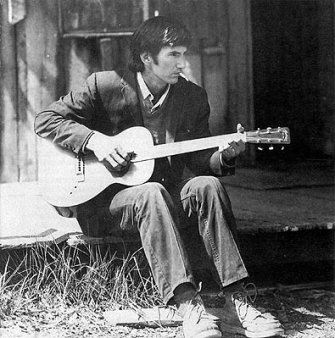

He says he got into the music thing by the fairly traditional route. The family travelled extensively when he was a child (“but I’m a Texan in my heart and by birth”) and he did well enough at school to head off to the University of Colorado to major in economics.

"Then I went to the University of Houston but by then I was playing guitar. I was supposed to be a lawyer from the time I was born but in that folk boom of about '65 I started on guitars.”

The childhood rambles became adulthood rambles as he continually packed up his guitar and headed to the next town -- and with it came the loneliness, the drinking and faster times. He was, for a long time, the lost soul reaching deeper and deeper into his own personal demons.

“Just wild times and a disregard for things, crazy stuff, wild chances," he says of that period, his words fragmenting into loose phrases. "Lots of booze and gambling as the song says, Wild Living.

"But now I've completely stopped everything.

"Like a lot of folks I was a person who couldn’t do things halfway. Now I can play guitar better and I’m not crazy all the time. I used to go right to the edge and I’m not sure where all that came from.

"Now I know how to handle the blues a lot better, but because of all that travelling and this and that you can get real alone. I’m just not as alone now. Maybe that was just a phase and this is a more comfortable one.

“I guess I’m more optimistic because of my son Will, but to me it doesn’t make any difference. I’m still not . . . run-of-the-mill . . . you know? I’m kind of joyfully pessimistic and I don’t have real severe attacks of manic depression any more.”

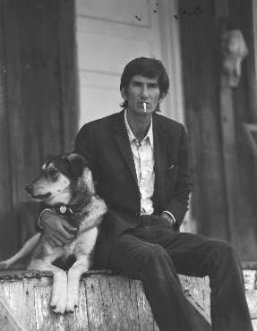

During the lost years Van Zandt was allegedly so well known by police in Austin they called him by his first name and during summer he would take himself alone into the wilderness of Colorado to confront the solitude and his demons again.

“I’ve always loved the mountains and I’d still be doing that, but I have responsibilities now. I have a little sailboat I spend a lot of time on now. It’s not the same but I did that [riding into the mountains] for years and years and I’d keep a horse somewhere around and just take off."

Van Zandt has now been back in Nashville, for the third time, for almost two years and although he says he never left music he often ignored the business side. With a new album out, At My Window, and a booking agent he is slowly accepting the business. But he sees the world very differently from most people.

“A lot of times you can write songs and they come true," he says departing at a tangent from a question about family.

“There have been songs I didn‘t write because I was afraid they rnight come true, kind of sad songs that I didn't want to hear. I have a couple of songs about my wife written way before I met her.

“I believe that can happen. I don’t believe you can sit down like voodoo and conjure up thing -- but you could write a song that set a path that something would take to happen and people near the song and started thinking about it and so that path was taken.

“You might write something like that . . . but I barely understand this world much less the next," he says as an afterthought.

He cites his song Tecumseh Valley (first recorded in ’68 and revisited regularly on live recordings, notably on the honestly entitled Live and Obscure album of ’87).

“I found out later that was all true down to where the town was and where the mountains were. The only difference was I though it would be in West Virginia but it was in Oklahoma."

When Van Zandt speaks like that it is clear he is tuned into a different wavelength from most, but it hasn’t stopped him penning some of the most finely compressed lyrics in American music today.

The chorus of Pancho and Lefty captures the essence of the rebellious spirit of the desperate and despairing in a few lines of boastful, hollow heroism: “All the Federales say, they could have had him any day, they only let him hang around . . . out of kindness I suppose."

Or The Catfish Song from At My Window which is sung with soft understanding “All you young ladies who dream of tomorrow, cling to today with its joy and sorrow, you’ll need your memories when youth melts away.”

And when Townes Van Zandt sings a simple couplet like “the darkness is passing, she’s never long-lasting" there is a light burning at the end of his long dark tunnel.

All things considered, he shouldn’t have made it this far, but he has and Townes Van Zandt -- a genuine survivor -- is still telling his hardwon truths.

Despite what he said, Townes Van Zandt struggled with those various demons all his life. He died on January 1, 1997. He was 52. Since his death there have been many tribute albums, notably Townes by his friend Steve Earle.

post a comment