Graham Reid | | 7 min read

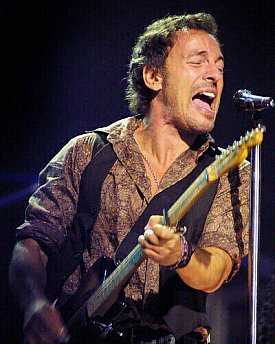

Bruce Springsteen won't forget his show

at Sydney's Cricket Ground last Saturday. He said so repeatedly and

meant it.

Losing power in a show can never be discounted as a possibility. But losing it twice would suggest alarmingly bad luck or poor technical support. Losing your stadium rock thump four times in the first hour, however?

Well, that makes a

show memorable.

The first time Springsteen and the E

Street Band were rendered mute was during his second song, War - the

air-punching and appropriate anti-war statement - and the sudden

silence deflated the early anticipation and whoop of the

almost-capacity crowd.

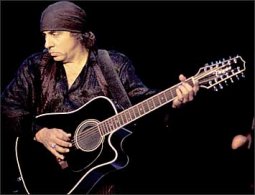

But where Marilyn Manson might have

thrown his teddy bear and Queens of the Stone Age walk off without

explanation, Springsteen and guitarist Steven Van Zandt collapsed

with laughter into each other's arms. Saxophonist Clarence "The

Big Man" Clemons and Springsteen's wife and guitarist, Patti

Scialfa, stepped to the front of the stage to get the crowd clapping

and singing along, "War, what is it good for? Absolutely

nothing."

When the sound returns the band do not

miss a beat - the mischievous-looking, diminutive guitarist Nils

Lofgren a Mini B at Springsteen's side - and the show roars into the

rocking No Surrender, then the emotionally uplifting title track of

Springsteen's post-September 11 album The Rising. The set steadies

itself and by Lonesome Day the sweat is pouring off the man some

still call The Boss.

After the second sudden loss of sound -

more laughter and Van Zandt menacingly leaning over the sound guy

like Silvio Dante, his character in The Sopranos - Springsteen jokes

that this was the recurring dream he'd had.

"But my analyst told me it was

just a dream," he laughs.

The bad dream halted their performance

twice more - the animated and amusing Van Zandt, a show in himself,

at one point sitting down and talking with the front row - and at the

end when he vamped lyrics in the style of a rock'n'soul revival show

Springsteen promised, "Tomorrow's gonna be a better day ... and

someone's gonna get get fired.

"No, just joking."

Oddly enough, while these problems

disrupted the momentum and long arc of the show - a performance of

tension and release ending in uplifting, celebratory rock'n'roll -

they didn't detract from a crowd-pleasing performance which ran

three-and-a-quarter hours, with Springsteen off stage only a few

minutes in that time.

By way of thanks to an audience which

sang his songs back to to him through each power failure - sudden,

none more than a minute - he spontaneously called up a few oldies the

band hadn't played in a while.

At that point it was obvious what a

consummately professional unit the well-drilled nine-piece E Street

Band are, violinist Soozie Tyrell dragged to the front for an

impromptu duel with The Big Man.

Some might say an outdoor Springsteen

show these days epitomises the bombast of 80s stadium rock, although

that accusation wilts when Springsteen makes his performances so

personal and obviously enjoyable. And when they pulled out the hoary

old bar-room rocker Ramrod you were reminded of their journeyman

Jersey Shore origins in clubs and battered ballrooms.

But Springsteen and the E Street Band

have come a long way in the thirtysomething years since, and although

the set reached back to that time for an impromptu Rosalita, it was

also as current as today's headlines when he included moving material

from The Rising.

One of Sydney's hip street-press

magazines not only snubbed commenting on Springsteen being in town,

but suggested where else you could go to avoid him - Beck, as it

happened. But that cynicism misunderstands what Springsteen's shows

are about.

Springsteen is a cypher for the

affirmation of faith in rock'n'roll redemption ("We learned more

from a three-minute record than we ever learned in school" in No

Surrender) and increasingly - especially in songs from The Rising -

the curative and cathartic power of music.

When he sings "I woke up this

morning to an empty sky" it is both about and beyond the events

of September 11. On The Rising these songs sound forced into the

context of a CD, in concert they co-exist with songs of affirmation

and healing from all points of his career and make better and bigger

sense.

Springsteen is also a man of his

post-Vietnam generation, so when he sings Born in the USA - in Sydney

his opener done on bottleneck slide guitar as a mournful,

regret-filled country blues - it encapsulated the disillusion of the

Reagan era when it was written. Understandably that doesn't mean much

if you were 2 years old when it came out in '84 and are now going to

dance clubs or Beck - but Springsteen audiences are predominantly

those who remember those chill years of Reaganomics and its various

offshoots. It means something just as powerful now about the current

disillusion.

And when he stepped forward for two

songs from The Rising with Scialfa at his side, there was a palpable

solemnity. To silence an audience in a sports stadium with just

guitar and voice is a rare skill and says much about the undeniable

power of his emotionally affecting songs. For him as much as his

audience. When Danny Federici's organ solo cut in on the holy sound

of You're Missing the look on Springsteen's face was as if he was

hearing it anew and for the first time fully understanding it.

In a performance which went from

flat-tack rock (Glory Days, Badlands, Backstreets and Thunder Road)

through poignant or populist pop (Bobby Jean, Dancing in the Dark)

and his new party-rock song Mary's Place, which sounds like it was

written around the time of Rosalita, Springsteen still banners the

belief that rock'n'roll can heal the pain of life through its sheer

celebratory quality.

It's rock'n'roll redemption from the

man who sings "Well, I got this guitar and I learned how to make

it talk". And so he does.

Of the new songs, the title of Countin'

on a Miracle speaks for itself. But even My City of Ruins -

apparently written about the Jersey Shore inner-city development but

taking new life post-September 11 - has as its chorus "rise up"

and Lonesome Day promises "It's all right".

And it is all right. This was a rock

show against the backdrop of nations at war, and he said thoughts

were with the American and Australian soldiers and innocent Iraqi

civilians.

Maybe it was a mere distraction or

diversion from those terrible events, but people cannot live with

tragedy all the time. "This too shall pass," he sings on

Lonesome Day and it could mean anything: The job you hate, the pain

of the separation you are going through, the loss of a loved one, or

a world going to oil-fuelled hell in the fires of ignorance and

anger.

Springsteen's songs can be that

ambiguous, that universal yet simultaneously personal.

They come from a man who writes himself

and his generation into them and gives himself away on stage, whether

it be through sweat-drenched passion as the new Man in Black, an

inheritor of Johnny Cash's mantle speaking for the dispossessed and

voiceless, or by his self-effacing humour which humanises a

performance in front of thousands of anonymous faces in the darkness.

"This earns me credit points

around the house," he quipped as he did a sexy shuffle towards

Scialfa.

She offered a bemused smirk, an

expression which says, "Who are you kidding? You're not The Boss

of me."

After yet another sound failure he

laughed and warned the audience not to use their cellphones, said

that they had people going round the nearby suburbs telling people

not to use their hairdryers. He made light of the problem - and the

band played on. And on, and on.

Somewhere around the two-hour mark he

makes like he is leaving the stage then, almost as an afterthought,

grabs the mike and says, "We can't go home now just as we got

this shit workin'." They play for another hour. Three and

a-quarter hours on stage?

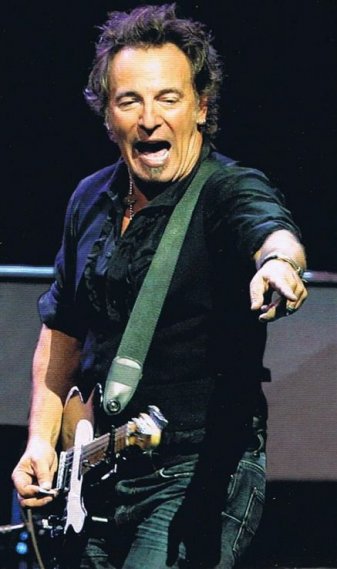

As a performer The Boss' energy is

undiminished. At 53 he still sprints across a stage and slides on his

knees to the feet of The Big Man for a sax solo, can still pogo and

play at the same time.

Yes, a Springsteen stadium show may

seem an anachronism these days, a throwback to the Eighties. But, even

putting aside his rare passion as a performer and the strength of his

band, his songs alone would carry the weight. They have written

themselves into people's lives, convey the aspirations and failed

dreams of his audience, whether real or imagined.

In Sydney the power may have gone, but Springsteen still had it.

post a comment