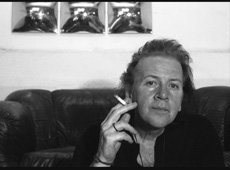

Graham Reid | | 7 min read

Chris Bailey: On the Avenue (from 54 Days at Sea, 1994)

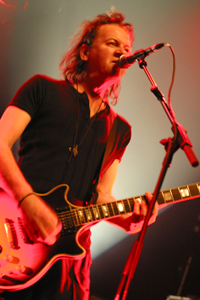

There were always a couple of good

reasons for liking the Saints, Brisbane’s punk-to-pop finest who

were fronted by sole constant Chris Bailey.

The first was Bailey running

intellectual rings around rock show host Dick Driver on national

television. The other was a great song.

What that song was came down to taste.

Maybe it was their first hit from ’77,

a piece of Buzzcocks/Ramones period-piece thrash called (I’m)

Stranded. Or maybe their bitter observations of their hometown in

Brisbane (Security City) from the following year, or the spare

story’n’six strings jangle of Let’s Pretend. Or the swirly rock

with Bonanza guitars of In Mirror.

Or Paradise (see clip below), their blissful

melancholy ballad of the kind Mick and Keith used to write around

their Waiting On a Friend period.

Or maybe it was their brutal duffing up

of Lipstick on Your Collar?

Yes, the Saints did it all . .. and

with a revolving-door membership policy which has seen something like

30 ex-Saints (including Ed Kuepper, jazz saxophonist Dale Barlow)

wander away from the Bailey experience.

And now Bailey has walked away from the

band he founded in Brisbane’s working class suburbs.

From a hotel room in Paris where he is

working on songs with Johnette Napolitano (of Concrete Blonde) he’s

happy to talk about his new solo album, 54 Days at Sea (recorded in

his adopted home of Malmo, Sweden, with a band which includes

Brazilian musicians) but equally comfortable with reflecting on the

Saints years, recently gathered on two Raven discs, Scarce Saints and

Songs of Salvation 1976-88.

“That first Raven collection is shit

if memory serves me correctly and was done without my knowledge,"

he says in beautifully modulated tones and with a rich laugh.

"I only ever listened to it once

and thought, ‘This guy [Ravens Glenn A. Baker] is charging money

for this?’ But I’m actually quite proud of the Saints.

“When they were good they were a

pretty terrific rock band in the classic sense and I liked the way we

managed to maintain a little of the non-conformist attitude when

there was the attitude that we should conform.

“And it’s funny, someone asked me

the other day if I'd ever do another Saints record . . I don't

remember ever formally disbanding the band, because we used to do

that every other week. So it doesn’t seem particularly relevant to

me at this time, but at some point, if I ever get senile and

nostalgic, who knows?

“One of the things I’ve enjoyed

over the past couple of years is being a free agent. The Saints were

pretty fluid in membership but it still felt like a rock band.

“One of the advantages of being a

Solo Artist, as it were, is that, while in my real life I try to be

monogamous, when it comes to music I’m a total slut and like to

sleep around. And I can duck off and write songs with others like

Johnette - or pretend to be a thespian from time to time."

That last reference is to his part as

the Pope in an Australian rock opera, The Prophets of Doom. ("There’s

a sex scene, so that’ll be interesting, The papacy, of course, has

a long tradition of getting more groupies than most rock singers and

being a lapsed Catholic, I’m some sort of authority on this.”)

But papal and Saintly matters aside,

what is engaging Bailey at present is working with the Salazar

brothers, the Brazilian musicians whose pan flutes he heard at a

street festival in Malmo and with whom he plays on 54 Days at Sea, a

collection of earthy songs which, as Rolling Stone said, sound like

latter-day Saints material but sway between Bolivian folk and the

nobler traditions of Australian pub rock. And with a curiously Celtic

feel?

“Exactly. When I first met Victor and

Oscar [Salazar], verbal communication wasn’t at a premium because

we spoke different languages. But one of the first things I said to

them was that it sounded like Irish music, which they quite liked.

“I think there’s a commonality

about folk music and if you think about it, the north-west of Spain

has Celtic connections and that has had some kind of influence

because Brazil was heavily raped by Portuguese.”

He notes the similarity in chordal

structures between Celtic music, Bolivian folk and “even in Swedish

and Eastern European folk.” But the thing he didn’t want to do on

54 Days at Sea was to be the white guy who goes to a less dominant

culture and rips it off.

He notes the similarity in chordal

structures between Celtic music, Bolivian folk and “even in Swedish

and Eastern European folk.” But the thing he didn’t want to do on

54 Days at Sea was to be the white guy who goes to a less dominant

culture and rips it off.

"To me this sounds like a rock

record and you don’t realise that it’s pan flutes taking the

melody line which might more traditionally have been done by horns.

The record was first released in Sweden and we got this snotty review

where someone said I’d gone soft and pan flutes were associated

with K-Tel coffee table albums, which I thought was just a little

insulting to Latin American culture . . . and like saying a violin

only belongs in a symphony orchestra. But that's rock critics for you

- some are pretty stupid.”

And as Dick Driver discovered, rock

journalists take on the articulate, witty Bailey at their peril. He

is a man who doesn’t suffer fools at all, let alone gladly, and a

conversation with him ranges across the effect of Sweden floating its

currency last year, the Coca-Cola-isation of rock (“it’s

depressing that the moist successful band around this summer is

Primal Scream. That's Showaddywaddy,” he snorts) and the political

climate in his adopted homeland.

Politics has always been a passion of

this avowed socialist but he speaks fondly of the conservative nature

of Sweden )”Lenin said if the Swedes were going to have a

revolution they’d probably go to the police station to ask

permission first - and that‘s very accurate”) and the advantage

of living in Malmo is that Copenhagen in Denmark is a 25-minute boat

trip away.

“Copenhagen is a fabulous city and

whereas Sweden is quite conservative and Protestant, all I have to do

is jump the boat and I’m out of it. Malmo only has about 250,000

people and it’s as boring as bat shit.

“But I’m a songwriter, so it’s

easy to focus on my work without distraction. And it’s exciting to

jump on the ferry. It’s like 'I’m going somewhere!' ”

Bailey has been going somewhere all his

life, however. He was born in Kenya when his parents were in transit

from Ireland to the suburban wasteland of Brisbane’s sprawling

western suburb of Inala, and discovered rock'n'roll as a teenager. He

left hot-wired Holdens behind for life on the road with his Saints.

And, as befits the son of an IRA

supporter, he was politically alert at an early age. Right from the

start, the Saints played benefit gigs for the Communist Party.

Then Bailey put the band on the road to

the UK, where they perversely stood out from the rest of the ratpack

of punks by refusing to conform to the obligatory short-haired look,

the band broke up, reformed, probably repeated that a dozen times and

yet always Bailey kept something called the Saints going.

The albums piled up, the music shifting

from three-chord thrash to reveal Baileys considerable melodic gifts.

The acoustic guitars came in, the records never sold as many as they

deserved, and Bailey remained a cult hero. He recorded in London and

New York, dumped on American corporate capitalism between songs on an

MTV special, honed his humour sharper but somewhere along the way

mellowed without compromise.

The wicked wit is still there, the

interest in Buddhism offering a modesty to counterbalance the

ferocious intellect. And now he’s in Malmo, Paris and a Sydney rock

opera before going to Brazil to play at Indian festivals with his new

band which includes those Salazar brothers. A Saint no more . . . and

no regrets.

“I wouldn't trade in my rather dodgy

little career," he says in that powerful, almost Queen’s

English voice. “In terms of what a working class Irish Catholic

immigrant to the New World could expect, rock'n'roll hasn’t been

that unkind to me. I doubt if I had been a factory worker I would

have become the sophisticated, jet-setting world traveller I have

become.

“There have been some pretty positive

perks and as a form of expression, if you had asked me at 20 if I

would still find rock'n'roll interesting at 37, I would have probably

said no. But the older I get, the more broad the possibilities seem.

"Rock'n'roll is useful and

exciting and it’s fucking music and all those arrogant teenage

things. But the way I approach it, and this is without sounding

egocentric, it doesn’t have to be dumb. There are a lot of thing

you can do with the text to make it interesting.

“I was born into that generation of

beat music, so I find it a little more entertaining than poetry. It

still works for me -- turn out the lights, open a bottle of wine.

Rock music is cinematic and a transcendental experience. Those three

chords -- it’s a Holy Thing.

“But let’s not continue with this,”

laughs this one-time Saint and soon-to-be-Pope. “I feel my papal

bull coming on!”

rob - Jun 22, 2010

Saw 'the saints' (post keupper) at the gladstone in chch in the early 80s- a great night, wonderful band (with brass! if memory is not dodgy) and Bailey is a terrific singer.

SaveI've always felt Ed Keupper is an under-rated gem of a performer. "Electrical Storm" his (first, I think) solo album (post laughing clowns, who also had some great moments) is a classic: maybe it's partly me, when I heard it and how it resonated, but I've found it enduringly good.

Subsequent efforts were a bit more hit and miss (though some great hits in there), as were live shows when I lived in Sydney (one dreadful night it looked like he had his latest girlfriend singing back-up, and it sounded... awful) though Honey Steels Gold is strong.

Not meaning to belittle Chris Bailey. "On the Avenue" (above) is great. I will check out some more.

post a comment